eBook - ePub

Hydraulic Fracturing Explained

Evaluation, Implementation, and Challenges

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Hydraulic Fracturing Explained

Evaluation, Implementation, and Challenges

About this book

Rocks mechanics legend Erle Donaldson, along with colleagues Waqi Alam and Nasrin Begum from the oil and gas consultant company Tetrahedron, have authored this handbook on updated fundamentals and more recent technology used during a common hydraulic fracturing procedure. Meant for technical and non-technical professionals interested in the subject of hydraulic fracturing, the book provides a clear and simple explanation of the technology and related issues to promote the safe development of petroleum reserves leading to energy independence throughout the world.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

Hydraulic Fracturing Explained

1.1 Introduction

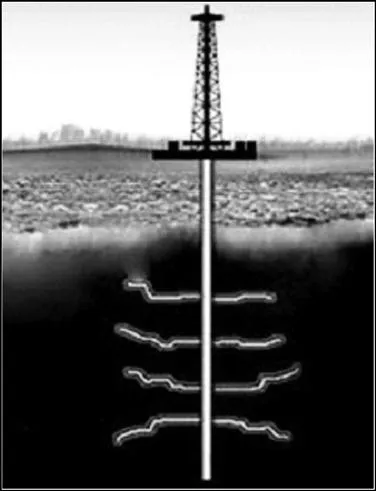

There is a lot of buzz going around regarding hydraulic fracturing—a process used to open new or existing cracks in the rock structures to produce oil and gas, also known as petroleum hydrocarbons. The cracks introduced in the rock act as channels to flow oil and gas from the rock into the well for production (see Figure 1-1). Hydraulic fracturing, also called “fracking,” has been used for more than 50 years; however, its use has significantly increased over the last decade as we try to produce oil and gas from a new source called gas-shale. In the past, when the supply of oil and gas was abundant and the risk of interruption in the supply chain was small, prices of these commodities were relatively low and fracturing shale to produce oil and gas was not considered economically feasible. With the constant uncertainty of supply and an ever increasing demand for energy, triggered by higher standards of living throughout the world, the price of oil has increased significantly. The price of gas has also increased except in certain parts of the world that have an abundance of this natural resource. Whereas oil has a developed infrastructure for shipment from almost every corner of the world, gas is still used locally in most cases because of the high cost of shipment where pipelines do not exist. Therefore, the price is tied to local, or regional, markets rather than the global market.

The high demand for energy has initiated rigorous investigations and development of methods that can produce traditional and non-traditional energy cost effectively. The petroleum industry, which currently produces the largest percentage of the total energy consumed, has developed and improved several technologies that can produce greater quantities of oil and gas. The process of hydraulic fracturing has also undergone substantial improvement over the years and that has led to production of additional quantities of oil and gas. Unlike the past, hydraulic fracturing is now being conducted more extensively and sometimes near densely populated and environmentally sensitive areas and, as a result, has encountered greater challenges.

1.2 Petroleum Hydrocarbons

Petroleum hydrocarbons, consisting of crude oil and natural gas, have been used as a source of energy for thousands of years. They have been used as a source of heat and some consider them divine in nature when ignited because of the light and energy they emit. The Chinese are said to have used natural gas for hundreds of years before Christianity. The “eternal fires” that became the object of worship could have been caused by natural gas seepage from cracks in the ground ignited by lightning. It was not until the 19th century that natural gas was used commercially for the benefit of society. In 1821, William A. Hart drilled the first well in Fredonia, New York, to produce natural gas from the ground. This began the period when harnessing this useful source of energy began to look possible. It was during this time that street lamps were converted to natural gas, but homes were still not connected to the natural gas source. Towards the end of the 19th century and in the early 20th century, street lights started using electricity and the use of natural gas shifted to domestic purposes. However, until the 1970s, natural gas was considered a by-product of the petroleum industry, where most of the interest was geared towards crude oil, and great quantities of gas produced along with oil were burned, called flaring, in the oilfields, which became so bright that one could read a newspaper at night.

Crude oil production also started in the 19th century when Edwin L. Drake drilled his first well in Titusville, Pennsylvania, in 1859. Before Drake sank his first well, people around the world gathered oil for centuries around “seeps” (places where oil naturally rose to the surface and came out of the ground). Crude oil was used both as an energy source and also for medicinal purposes. Natural gas is often produced in association with crude oil, which in the past was mostly flared due to high transportation cost. With the depletion of oil reserves and higher demand for energy and synthetic products made from hydrocarbons, natural gas now has become a more important energy source. Its use and production has increased tremendously, facilitated primarily through advancements in drilling and production technologies, transportation technologies, and environmental concerns of alternative sources of energy.

1.2.1 Origin of Petroleum Hydrocarbons

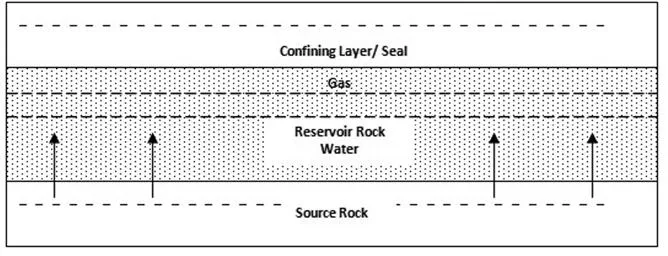

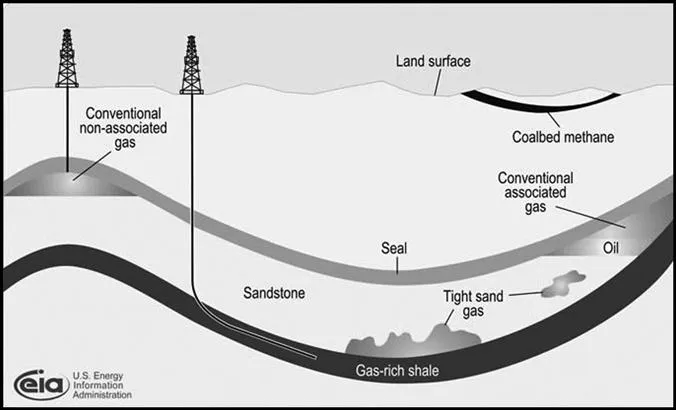

Petroleum hydrocarbons exist in pore spaces of rocks in the subsurface, like water in a sponge. The primary difference is that rock cannot be squeezed to extract hydrocarbons. Heavier components of the hydrocarbon that are liquid are referred to as “crude oil” or “oil” while the lighter components are referred to as “natural gas” or “gas.” Petroleum is a complex mixture containing thousands of different compounds (Tiab and Donaldson, 2012). Its composition can vary depending upon the environment in which it was formed. It is composed primarily of carbon and hydrogen and may contain other impurities. Crude oil consists of compounds that generally have more than five carbon atoms and are liquid. Natural gas predominantly consists of methane (a molecule containing one atom of carbon and four atoms of hydrogen) and may or may not be associated with crude oil. It also may contain some heavier hydrocarbons such as ethane, butane, propane, and even some liquid hydrocarbons, but their percentage of the total composition is generally small and varies from place to place. Hydrocarbons are formed in nature by the decomposition of organic matter under favorable conditions of pressure and temperature over millions of years in sedimentary rocks, generally shale, called “source rock.” The composition of the organic matter along with the conditions of pressure, temperature, and time determine if oil or gas is formed in the source rock. Shale is a tight (very low permeability) formation in which oil or gas can move, but only slowly. Permeability of a rock defines how easily fluid can flow through the pores of the rock. Over millions of years, some of the oil and/or gas have migrated from the source rock, generally shale, and accumulated in more permeable formations, such as sandstone or carbonate rock formations, called “reservoir rocks” (Gidley et al., 1989). Reservoirs have confining layers, also called “seals,” of impermeable rocks surrounding it through which the oil and/or gas cannot escape or migrate any farther. Reservoir fluids separate out in the reservoir rock due to their density differences, with gas being the lightest on top followed by oil and then water (see Figure 1-2). Reservoirs are, generally, substantially more complex than the horizontal pancake type layers shown in the figure. It is relatively easy to produce hydrocarbons from reservoir rocks because of their moderate to high permeability. Most of the oil and gas in the past have been recovered from land-based reservoir rocks. With the depletion of these reservoirs and ever higher demands for oil and gas, new technologies and frontiers are being explored. One such technological development has been in the area of gas production from the shale formations (which is a source rock) with extremely low permeability and, in many places, contains substantial amounts of hydrocarbons. These hydrocarbons are commonly called “shale-oil” and “shale-gas.” The technology also facilitates production from other tight rock formations and coal beds that are not shale but have very low natural permeability. The technological leap that allows us to tap into these resources of hydrocarbons consists of modern methods of directional drilling and fracturing. The directional drilling method provides the flexibility of constructing the well vertical, or at a slanting angle, to access the bulk of the hydrocarbon producing formation (see Figure 1-3). The fracturing process increases the permeability of the rock facilitating production of hydrocarbons, albeit with its own share of challenges, such as concerns with respect to the protection of groundwater, surface water, air, and farmlands.

1.3 Petroleum Reserves in Shale

The reserve estimate of the amount of petroleum hydrocarbons still in the ground constantly keeps changing because of new discoveries and depletion of existing resources. In shale, petroleum hydrocarbons are found in shale “plays,” which are shale formations containing large quantities of oil and/or natural gas. These shale formations are geologically similar and are in the same geographical region. Estimation of reserves and extraction of oil and gas from these shale formations is still a challenge for the industry because of their complex nature. Production from these formations, using current technology, requires extensive hydraulic fracturing that allows the fluid to flow from the rock matrix into the production well.

Total proved world oil reserves (proved reserves are estimated quantities that analysis of geologic and engineering data demonstrates with reasonable certainty are recoverable under existing economic and operating conditions) are estimated to be a little over 1.3 trillion barrels (a barrel is equal to 42 gallons) (The US Energy Information Administration's International Energy Statistics, 2009). Shale oil is not a significant contributor to the total proved oil reserves. At the current consumption rate of approximately 75 million barrels per day (Journal of Petroleum Technology, May 2012), it should last us about 50 years. However, the consumption rate is expected to rise significantly.

According to the US Energy Information Administration's (EIA) Annual Energy Outlook 2012, estimated world recoverable reserve of shale gas is 6,600 trillion cubic feet (Tcf), which is more than one-third of the total conventional gas reserve. The estimate is based on data obtained for gas-shale formations (see Figure 1-4) around the world. Many areas that have the potential of adding substantially more reserves have not been studied. Access to this vast resource will require hydraulic fracturing unless some other technological breakthrough is achieved that is more cost effective and safe.

Table 1-1 shows that the potential of shale to meet world demand is significant. In some countries, such as France, where the estimated technically recoverable shale-gas reserve is 180 Tcf and where 98% of natural gas is currently imported, safe exploration and production of shale-gas could be of tremendous benefit to the country. Situations in South Africa, Pola...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Foreword

- Preface

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Nomenclature

- CHAPTER 1. Hydraulic Fracturing Explained

- CHAPTER 2. Evaluation of Gas-Shale Formations

- CHAPTER 3. Rock Mechanics of Fracturing

- CHAPTER 4. Fracture Fluids

- CHAPTER 5. Field Implementation of Hydraulic Fracturing

- CHAPTER 6. Environmental Impacts of Hydraulic Fracturing

- APPENDIX A. Viscosity

- APPENDIX B. Surfactants, Emulsions, Gels, Foams

- APPENDIX C. Calculations

- Glossary

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Hydraulic Fracturing Explained by Erle C. Donaldson,Waqi Alam,Nasrin Begum in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Fossil Fuels. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.