- 596 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Subsea Optics and Imaging

About this book

The use of optical methodology, instrumentation and photonics devices for imaging, vision and optical sensing is of increasing importance in understanding our marine environment. Subsea optics can make an important contribution to the protection and sustainable management of ocean resources and contribute to monitoring the response of marine systems to climate change. This important book provides an authoritative review of key principles, technologies and their applications.The book is divided into three parts. The first part provides a general introduction to the key concepts in subsea optics and imaging, imaging technologies and the development of ocean optics and colour analysis. Part two reviews the use of subsea optics in environmental analysis. An introduction to the concepts of underwater light fields is followed by an overview of coloured dissolved organic matter (CDOM) and an assessment of nutrients in the water column. This section concludes with discussions of the properties of subsea bioluminescence, harmful algal blooms and their impact and finally an outline of optical techniques for studying suspended sediments, turbulence and mixing in the marine environment. Part three reviews subsea optical systems technologies. A general overview of imaging and visualisation using conventional photography and video leads onto advanced techniques like digital holography, laser line-scanning and range-gated imaging as well as their use in controlled observation platforms or global observation networks. This section also outlines techniques like Raman spectroscopy, hyperspectral sensing and imaging, laser Doppler anemometry (LDA) and particle image velocimetry (PIV), optical fibre sensing and LIDAR systems. Finally, a chapter on fluorescence methodologies brings the volume to a close.With its distinguished editor and international team of contributors, Subsea optics and imaging is a standard reference for those researching, developing and using subsea optical technologies as well as environmental scientists and agencies concerned with monitoring the marine environment.

- Provides an authoritative review of key principles, technologies and their applications

- Outlines the key concepts in subsea optics and imaging, imaging technologies and the development of ocean optics and colour analysis

- Reviews the properties of subsea bioluminescence, harmful algal blooms and their impact

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Introduction and historic review of subsea optics and imaging

1

Subsea optics: an introduction

O. Zielinski, University of Oldenburg, Germany

Abstract:

The interaction of light with water and its constituents is of major relevance to several physical, biological and chemical processes in the marine environment. It is the scope of this chapter to introduce the topic of subsea optics as an interdisciplinary field of natural and engineering sciences focused on the utilisation of light below the sea’s surface. Fundamental radiometric quantities, optical properties and classifications will be introduced to the reader, providing the framework of marine optics terminology needed throughout the book.

Key words

optical properties

light field

radiometry

subsea optics

colour classification

1.1 Light within aquatic media

Solar radiation is a fundamental prerequisite of life on Earth. It provides energy to heat the land and the sea, it drives the world’s atmospheric and ocean currents, it enables photosynthesis, and it influences the health and behaviour of many organisms. Arising from this, natural water bodies and their constituents are also strongly influenced by light abundance. Integral understanding of light interactions is a key element to understand and predict environmental processes in aquatic ecosystems (Dickey et al., 2011). Furthermore, light is, together with sound, among the primary approaches in probing aquatic media (Sanford et al., 2011). Utilising the interactions of light with water constituents via optical sensors enables an assessment of spatial, temporal, as well as spectral variability of optical properties and proxies that are associated to them (e.g. Daly et al., 2004; Zielinski et al., 2009).

While this book will refer to marine environments in general and to subsea topics specifically, it has to be emphasised that the physics of aquatic optical properties is also valid for freshwater systems, and even for industrial locations such as waste-water plants. This chapter strives to provide the reader with the framework of marine optics terminology needed throughout the book, introducing fundamental radiometric quantities, optical properties and classifications. While this inauguration into the discipline of aquatic optics is meant to be short and specific to the scope of the book and its constituent chapters, more detailed introductions are provided, for example by the textbooks of Kirk (2011), Arsti (2003), Mobley (1994) or Jerlov (1976).

The term ‘subsea’ is often used with reference to underwater technologies, equipment and methods. Frequent application of the subsea prefix is found in the oil and gas industry for underwater oil field facilities. Throughout this book we will refer to ‘subsea optics’ as an interdisciplinary field of natural and engineering sciences focused on the utilisation of light below the sea surface, in the context of environmental and industrial objectives.

1.2 Fundamentals of marine optics

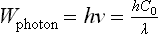

Let us assume a narrow collimated beam of monochromatic light of a wavelength λ typically given in nanometres (1 nm = 10–9 m). Without loss of generality an Argon-ion (Ar +) laser with a resonance wavelength of 488.0 nm is chosen. Looking into the physics of this laser beam, it consists of a stream of energy quanta, called photons, travelling at the speed of light (C0), which is constant for a given medium. Wave–particle duality of matter and energy teaches us that both properties, particle-like and wave-like behaviour, need to be considered to explain photon propagation and interaction. The energy of a single photon (Wphoton) is linked to its frequency (ν), in units of s–1 (Hz), and is inversely related to λ

where Planck’s constant h = 6.626 × 10–34 J s. Since we refer to light in the water, we are actually looking at photons moving through a medium other than vacuum. The speed of light, which is approximately 2.998 × 108 m s–1 in vacuum, is thus slowed down in relation to the refractive index (n) of the medium, which is varying itself with temperature, salinity and wavelength. Assuming nWater ~ 1.345 (which holds true for a salinity of S = 35 ‰ and a temperature of T = 10°C for our chosen λ = 488.0 nm), this leads to CWater ~ 2.229 × 108 m s–1 and, since energy and frequency stay unchanged, to a lower wavelength. However, since physical interactions are based on energy, and since c0 and λ change in unison, Equation [1.1] is valid in vacuum as in water and all references to λ within this book are made to vacuum conditions. The energy of our Ar + -laser photons thus calculates to W488 nm = 4.07 × 10–19 J, independently of the medium.

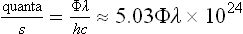

Since there are a high number of photons emitted over time, the laser beam can be considered in terms of its radiant flux (optical power). This monochromatic radiation flux, expressed as quanta per second, can be converted to watts or with respect to a specific wavelength to the spectral radiant power Φ(λ), which has units of W nm–1 representing a fundamental quantity in spectroradiometry. In reverse, a given radiant flux Φ of a wavelength λ can be converted to quanta s–1 using the relation

A radiant flux of 1 W from our Ar + -laser at 488.0 nm thus contains 2.455 × 1018 quanta s–1, whereas the same radiant flux at 632.8 nm, the typical wavelength of a helium–neon laser, contains 3.183 × 1018 quanta s–1, given the fact that the individual energy of red photons (λ = 632.8 nm) is 23% lower than the energy of blue photons (λ = 488.0 nm). While technological applications often consider radiant power the crucial factor for system performance, some bio-optical processes such as photosynthesis are driven by the number of quanta of accessible wavelengths, expressed in units of mole photons s–1 m–2 or einst s–1 m–2, where one einstein is one mole (6.023 × 1023) of photons.

Propagation of the light within the medium is in the first instance influenced by absorption and elastic scattering processes. Other influencing factors include inelastic scattering and emission of photons due to fluorescence and luminescence, which will be discussed later.

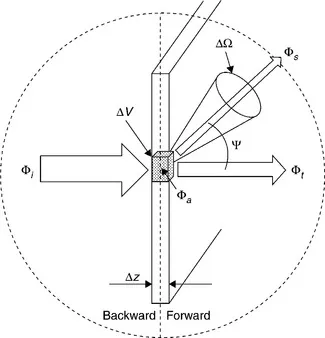

Now let us assume the above defined laser beam will intersect a thin layer (thickness Δz) of aquatic medium, forming a small volume (ΔV) of interaction between photons and medium (Fig. 1.1). Outside this volume, no interaction happens. Reflection and refraction at the volume’s surfaces are neglected. The medium is homogeneous inside this volume and no inner energy sources or energy transfers (wavelength conversions) occur. Effects of polarisation are not considered either.

1.1 Defining IOPs by interaction of a collimated beam of light with a small volume of aquatic medium.

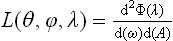

Designing an appropriate photo-detector, we measure the full distribution of spectral radiant power Φ(λ) in polar coordinates (nadir angle θ and azimuthal angle ϕ). In reality, such an instrument measuring spectral radiant power will detect the photons of a geometrically defined solid angle (ω) projected on the detector area (A) leading to the operational definition of unpolarised spectral radiance (L in units of W m–2 nm–1 sr–1) defined as

from which all other radiometric quantities can be derived (Mobley, 1994).

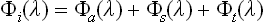

In our experiment we will observe that only a fraction of the incident spectral radiant power Φi(λ) of the laser beam is transmitted through the olume without change of direction, called Φt(λ). Part of the light will be scattered in different directions (angle ψ) making up Φs(ψ, λ). Summing up the scattered power from all directions we will get Φs(λ). The rest of the incident energy will be absorbed within the volume Φa(λ). With the prerequisites made above, conservation of energy gives us:

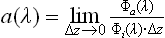

If Δz now tends to be infinitesimally small, we get:

• absorption coefficient a(λ)

• volume scattering fun...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Contributor contact details

- Woodhead Publishing Series in Electronic and Optical Materials

- Preface

- Part I: Introduction and historic review of subsea optics and imaging

- Part II: Biogeochemical optics in the environment

- Part III: Subsea optical systems and imaging

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Subsea Optics and Imaging by John Watson,Oliver Zielinski in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Materials Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.