- 350 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Lignin in Polymer Composites

About this book

Lignin in Polymer Composites presents the latest information on lignin, a natural polymer derived from renewable resources that has great potential as a reinforcement material in composites because it is non-toxic, inexpensive, available in large amounts, and is starting to be deployed in various materials applications due to its advantages over more traditional oil-based materials.

This book reviews the state-of-the-art on the topic and their applications to composites, including thermoplastic, thermosets, rubber, foams, bioplastics, nanocomposites, and lignin-based carbon fiber composites. In addition, the book covers critical assessments on the economics of lignin, including a cost-performance analysis that discusses its strengths and weaknesses as a reinforcement material.

Finally, the huge potential applications of lignin in industry are explored with respect to its low cost, recyclable properties, and fully biodegradable composites, and the way they apply to the automotive, construction, and packaging industries.

- Reviews the state-of-the-art on the topic and their applications to composites, including thermoplastic, thermosets, rubber, foams, bioplastics, nanocomposites, and lignin-based carbon fiber composites

- Presents the essential processing and properties information for engineers and materials scientists, enabling the use of lignin in composites

- Provides critical insight into the applications and future trends of lignin-based composites, including advantages, shortcomings, and economics

- Includes a thorough coverage of extraction, modification, processing, and applications of the material

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Sources of Lignin

Shayesteh Haghdan, Scott Renneckar, and Gregory D. Smith Department of Wood Science, Forest Sciences Centre, The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada

Abstract

Woody plants contain lignin that serves as a key structural polymer that adds rigidity and strength to the plant cell wall. Lignification occurs after the secondary cell wall polysaccharide network is deposited, limiting access to the cell wall from wood-destroying organisms as well as changing the hydrophilicity of the cell wall. While lignin is referred to in general terms, there are three types of monomers involved in lignification, and this ratio is dependent across lignocellulose biomass types such as grasses, angiosperms, and gymnosperms. Furthermore, isolated lignin is a heterogeneous polymer with its physical and mechanical properties highly dependent on biomass source, location within the cell wall, delignification methods, and purification schemes. Fortunately, the dominant lignin source available is commercial lignins formed as a by-product of the pulp and paper industry and generally classified as hardwood and softwood lignins. Despite the production of large quantities of lignin during delignification, the majority of lignin is burned for energy generation. Examples of commercialized added value materials from lignin are limited, and unlocking new lignin conversion strategies holds enormous potential to enable a green economy for sustainable consumption.

Keywords

Applications; Lignin; Properties; Pulp and paper; Wood1. Introduction to Lignin

The term lignin is derived from the latin name lignum meaning wood (Mccarthy and Islam, 1999). It was first isolated from wood in a scientific report by the French scientist Payen (1838) and later given its current name in 1857 by Schulze. Lignin was initially described as an incrustant of cellulose, and this point is insightful as lignification occurs after the deposition of the polysaccharide framework. In an extremely simplified view it is analogous to the matrix material for a fiber-reinforced composite. Lignin has several functions with the cell wall such as changing the permeability and thermal stability, but it has the primary function to serve as a structural material that adds strength and rigidity to plant tissue. In the sense lignin distinguishes lignocellulosic biomass from other polysaccharide-rich materials, by reinforcing the polysaccharide scaffolding of the cell wall. Its performance is so effective that it allows trees to outcompete other plants for sunlight forming the largest organisms on the planet.

As lignin constitutes 15–40% of dry weight of woody plants, it is the most abundant aromatic polymer on the earth and the second most abundant organic polymer after cellulose. Based on yearly biomass growth rates, the overall production of lignin is on the order of 5–36 × 108 tons (dos Santos et al., 2014). Hence, lignin has the potential to be an important source of aromatic chemicals for the chemical industry, arising from the conversion of modern era CO2, and its efficient utilization solves a potential puzzle in creating valuable by-products in a biorefinery scheme. This reasoning is because if wood is converted to the billion ton scale for biofuels and biochemicals, then there will be greater than 300 million tons of lignin potentially available. To put this in perspective it is roughly the size of the global polymer market.

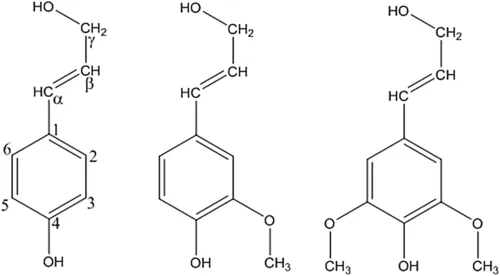

As mentioned above, lignin is an aromatic polymer. The monomeric precursors have a phenolic ring with a three carbon side chain providing a basic nine carbon structure commonly referred to as a C9-unit and/or phenylpropane unit as shown in Figure 1.

The side chain is terminated with a primary hydroxyl group on the Cγ, while the Cα and Cβ are connected together with an unsaturated bond. The phenolic ring is methoxylated (–OCH3) to various degrees, dependent upon the species; p-coumaryl alcohol, coniferyl alcohol, and sinapyl alcohol have none, one, or two methoxyl groups at the 3- and 5-positions, respectively. Based on the lignin monomeric composition involved in polymerization, the resulting lignin is classified into three types: (1) lignin that contains mainly coniferyl alcohol is called guaiacyl (G) lignin and is found predominantely in gymnosperms; (2) lignin formed from sinapyl alcohol is called syringyl lignin (S) and mixtures of G and S are found in angiosperm lignin; and (3) lignin which incorporates p-coumaryl alcohol is p-hydroxyphenyl (H) lignin, and the three types of monomers are commonly found in grasses. Overall hardwoods have a G:S ratio that approaches 1:2 and softwoods have approximately 95% G lignin (Lin and Dence, 1992). One simple way of determining this ratio is based on the methoxy content of the lignin, while other techniques can be used to identify the specific C9 structures either directly using nuclear magnetic spectroscopy or determined from the derivatized thioacidolysis products using gas chromatography.

Figure 1 Examples of C9 monomers: p-coumaryl alcohol, coniferyl alcohol, and syringyl alcohol.

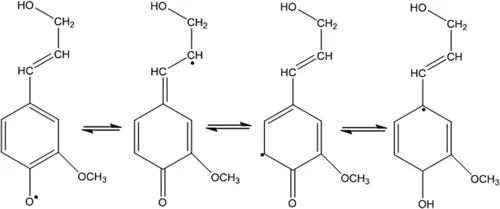

The monomeric units are built into the macromolecule lignin from the oxidative radical coupling of these substructures (Adam et al., 2011; Dinis et al., 2009; De la Cruz, 2014; Bowyer et al., 2007). Lignification is initiated when a phenolic hydroxyl hydrogen atom is abstracted by the enzyme peroxidase to form a phenoxy free radical, typically referred to as dehydrogenative polymerization, as described by Freudenberg and Neish (1968). This phenoxy-free radical will then delocalize to both aromatic and side chain carbon atoms by the process of resonance stabilization (Figure 2).

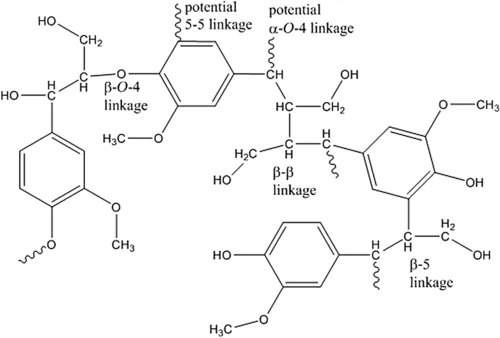

Coupling of these radicals may form ether linkages, carbon–carbon bonds, and bonds occasionally to more than one other phenylpropane unit. Based on the stability of the radical at each location, there is a higher probability that certain carbons will host the free radical. This, in turn, will provide preferred linkages between lignin units. It has been determined that approximately 50% of these bonds are β-O-4 ether type (De la Cruz, 2014; Bowyer et al., 2007) with other bonds associated such as β-5, β-1, β-β, and 5-5 (Figure 3). It is evident that the Cγ retains its hydroxyl group through this process, providing the native lignin opportunity to also retain a certain level of hydrophilicity. Furthermore, as indicated in Figure 3, the benzylic carbon (at the Cα) is typically highly unstable and undergoes reactions with nucleophilic compounds. These reactions can lead to the formation of a secondary hydroxyl group at the Cα by reaction with water which is a reactive site for linkages to carbohydrates creating lignin–carbohydrate complexes. These linkages formed to the polysaccharides are both ether and ester linkages dependent upon the functional groups of the monosaccharide (Fengel and Wegener, 1983).

Figure 2 Resonance stabilization of radicals that lead to interunit linkages in lignin.

Figure 3 Examples of interunit connections in lignin. Note, the diagram is to simply illustrate possible linkages and this structure is not a representative “segment” of lignin.

Analysis of lignin impacts several changes to its native state making it difficult to have an exact structure of lignin within the cell wall. However, there are isolation methods that can be used to get a better idea of the characteristics of a less severely modified lignin. One such method involves the resizing of wood into a fine flour through ball milling, using cellulose-degrading enzymes to remove the bulk of the polysaccharides and then an acidolysis reaction to break several of the lignin ...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contributors

- Editor's Biography

- Preface

- 1. Sources of Lignin

- 2. Extraction and Types of Lignin

- 3. Lignin Interunit Linkages and Model Compounds

- 4. Techniques for Characterizing Lignin

- 5. Lignin-Based Aerogels

- 6. Lignin Reinforcement in Thermoplastic Composites

- 7. Lignin Reinforcement in Thermosets Composites

- 8. Lignin Reinforcement in Bioplastic Composites

- 9. Lignin-Based Composite Carbon Nanofibers

- 10. Lignin-Reinforced Rubber Composites

- 11. Lignin-Derived Carbon Fibers

- 12. Lignin-Based Foaming Materials

- 13. Applications of Lignin Materials and Their Composites (Lignin Applications in Various Industrial Sectors, Future Trends of Lignin and Their Composites)

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Lignin in Polymer Composites by Omar Faruk,Mohini Sain in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Materials Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.