- 560 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

In the years since it first published, Neuroeconomics: Decision Making and the Brain has become the standard reference and textbook in the burgeoning field of neuroeconomics. The second edition, a nearly complete revision of this landmark book, will set a new standard. This new edition features five sections designed to serve as both classroom-friendly introductions to each of the major subareas in neuroeconomics, and as advanced synopses of all that has been accomplished in the last two decades in this rapidly expanding academic discipline. The first of these sections provides useful introductions to the disciplines of microeconomics, the psychology of judgment and decision, computational neuroscience, and anthropology for scholars and students seeking interdisciplinary breadth. The second section provides an overview of how human and animal preferences are represented in the mammalian nervous systems. Chapters on risk, time preferences, social preferences, emotion, pharmacology, and common neural currencies—each written by leading experts—lay out the foundations of neuroeconomic thought. The third section contains both overview and in-depth chapters on the fundamentals of reinforcement learning, value learning, and value representation. The fourth section, "The Neural Mechanisms for Choice, integrates what is known about the decision-making architecture into state-of-the-art models of how we make choices. The final section embeds these mechanisms in a larger social context, showing how these mechanisms function during social decision-making in both humans and animals. The book provides a historically rich exposition in each of its chapters and emphasizes both the accomplishments and the controversies in the field. A clear explanatory style and a single expository voice characterize all chapters, making core issues in economics, psychology, and neuroscience accessible to scholars from all disciplines. The volume is essential reading for anyone interested in neuroeconomics in particular or decision making in general.- Editors and contributing authors are among the acknowledged experts and founders in the field, making this the authoritative reference for neuroeconomics- Suitable as an advanced undergraduate or graduate textbook as well as a thorough reference for active researchers- Introductory chapters on economics, psychology, neuroscience, and anthropology provide students and scholars from any discipline with the keys to understanding this interdisciplinary field- Detailed chapters on subjects that include reinforcement learning, risk, inter-temporal choice, drift-diffusion models, game theory, and prospect theory make this an invaluable reference- Published in association with the Society for Neuroeconomics—www.neuroeconomics.org- Full-color presentation throughout with numerous carefully selected illustrations to highlight key concepts

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Basic Methods from Neoclassical Economics

Keywords

Introduction

Rational Choice and Utility Theory: Some Beginnings

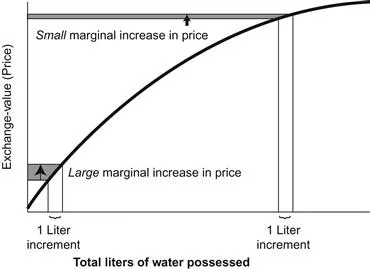

Early Price Theory and the Marginal Revolution

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- List of Contributors

- Introduction: A Brief History of Neuroeconomics

- Part I: The Fundamental Tools of Neuroeconomics

- Part II: Neural and Psychological Foundations of Economic Preferences

- Part III: Learning and Valuation

- Part IV: The Neural Mechanisms for Choice

- Part V: Brain Circuitry of Social Valuation and Social Choice

- Appendix. Prospect Theory and the Brain

- Index