![]()

Methane formation and cellulose digestion

![]()

ACETATE, A KEY INTERMEDIATE IN METHANOGENESIS

R.A. Mah, Center for the Health Sciences, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90024, USA

R.E. Hungate and Kyoko Ohwaki, Department of Bacteriology, University of California, Davis, California 95616, USA

Abstract

Acetate is the chief precursor of methane in anaerobic fermentations. Methane can be formed from H2 and CO2 by most methanogenic bacteria, but these substrates can also be converted to acetate by Clostridium aceticum, isolated from sludge. Its activity may increase the fraction of methane arising from acetate. Anaerobic 2% Ca acetate mineral enrichments forming methane were transferred weekly with a one-sixth volume inoculum. The rate of methane production was 9 μmoles ml−1 day−1. Methanosarcina barkeri was the chief methanogen in the enrichment but numerous non-methanogens were present, three of which were isolated. In pure cultures of M. barkeri in medium supplemented with trypticase and yeast extract the rate of methanogenesis was 20 ymoles ml−1 day−1, and similar supplementation of the enrichment culture increased the rate from 9 to 23 μmoles ml−1 day−1. The rate of methane production was affected not only by M. barkeri but also by the non-methanogens in the enrichment. Microbiological analyses of methanogenic ecosystems is recommended as a means to provide clues of value in practical applications.

It is a pleasure to participate in a symposium exploring possibilities to augment world energy sources by exploiting microbial activities. We are greatly indebted to Dr. Schlegel and the Institut für Mikrobiologie for organizing this meeting and appreciate the financial support of the United Nations Institute for Training and Research and the Bundesministerium für Forschung und Technologie.

The preceding papers have reviewed the photosynthetic storage of renewable light energy in chemical form by various ecosystems. An inventory of energy resources shows (table 1) that sunlight constitutes more than 99.94% of the total energy (excluding nuclear) available annually on Earth.

Table 1

Potential Non-nuclear World Power

| Kind | Amount in Kcal year−1 |

| Geothermal | 0.008 |

| Tidal | 0.09 |

| Water power | 20 |

| Coal, oil and gas | 80 |

| Sunlight | 170000 |

Although only a small fraction, 0.12%, of the light is used in photosynthesis the energy stored in chemical form (table 2) is about twice the annual fuel consumption.

Table 2

Maximum World Agricultural Production

| Kind | Amount in kcal year−1 |

| Arable lands | 120 |

| Grazing lands | 25 |

| Forests | 23 |

| Seas | 32 |

| Total | 200 |

This session on methanogenesis will explore potentials and problems in microbial generation of methane from available agricultural products. The processes to be considered are anaerobic. Aerobic microbial metabolism of organic matter converts energy chiefly into the form of microbial cell bodies whereas anaerobically cells are minor and the reduced carbon in the waste fermentation products contains most of the substrate energy, available through oxidation. In a complete anaerobic breakdown of organic matter carbon atoms are converted to their most reduced or most oxidized form, i.e., to the gases, CH4 or CO2.

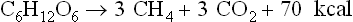

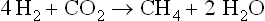

For anaerobic reactions to occur the substrate carbon atoms must be in an intermediate oxidation state, and energywise the most favorable condition for rapid and complete conversion of the organic matter to CO2 and CH4 is provided when the C, H, and O atoms are in the ratio of CH2O, i.e. carbohydrate. The conversion of carbohydrate to CH4 and CO2 is accompanied by a ten percent decrease in the potential energy, but ninety percent of the energy available through oxidation of the initial carbohydrate can be derived through oxidation of the reduced fermentation product, methane.

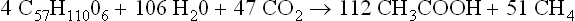

Proteins, fats and many other compounds can also be converted to CO2 and CH4 but they are not as abundant as carbohydrates, and the proteins are too valuable to be used as fuel. Lignins, comprising up to 30% of woody plant material, are a handicap to complete anaerobic conversion of plant materials. Lignins are relatively indigestible anaerobically, and their intimate association with carbohydrates reduces the digestibility of the carbohydrate components in the lignified plants. Thus carbohydrates, and possibly fats, are the chief renewable substrates suitable for anaerobic conversion to CO2 and CH4.

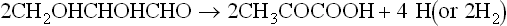

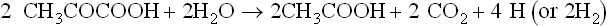

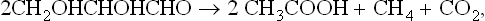

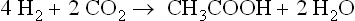

A carbohydrate such as hexose can be converted to methane in the overall process summarized in equation 1, but this includes two separate pathways by which methane originates. The two triose molecules derived from the hexose are fermentated in a fashion such that methane arises either by reduction of CO2 (Barker, 1936a)or by the splitting of acetate (Buswell and Sollo, 1948). Equations 3 to 5 illustrate how the hydrogen to reduce CO2 is obtained during breakdown of the two triose molecules derived from hexose.

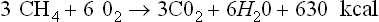

The hydrogen made available in these reactions is used to reduce CO2 to CH4.

In summary,

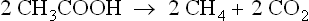

using one-third of the available hydrogen to produce one methane molecule. The acetate is then split to produce the remaining two-thirds of the methane.

Many fermentations give rise to products such as ethanol, or propionic and butyric and higher acids, converted in sludge to methane, in part by reduction of CO2 with the hdyrogen obtained by dehydrogenation of the substrate to acetate, in part by splitting of the acetate into methane and CO2. With these fermentations also, acetate constitutes two-thirds of the carbohydrate initially attacked, and is the source of two-thirds of the methane. If a fat such as stearate is the initial substrate it can be converted by β-dehydrogenation to acetate, with the hydrogen used to reduce exogenous CO2 to methane. In this process the fraction of methane arising from acetate is slightly less than 69% of the total.

In the sludge fermentation of municipal and domestic wastes, tracer studies indicate that the fraction of methane arising from acetate is about 73% (Jeris and McCarty, 1965; Smith and Mah, 1966), 4 and 6% higher than the theoretical values for fats and carbohydrates, respectively. A possible explanation for this higher value is the occurrence in sludge of the acetigenic reaction discovered by Wieringa (1938) in which H2 and CO2 are converted into acetic acid by a spore-forming bacterium, Clostridium aceticum, isolated from Dutch canal mud.

One of us (KO) has isolated presumably similar bacteria from sewage sludge (Ohwaki, 1975) at Davis. Mylroie (1953) earlier showed at Pullman that H2 and CO2 added to sewage sludge were actively converted to acetate with little formation of methane. The numbers of acetigenic bacteria at Pullman were not large, ranging from 106 to 108 ml−1. In pure culture this species grows rapidly, a ml of culture absorbing as much as 130 μmoles of H2 day−1. Yeast extract is required for growth, and vitamin B12, folate, Se, Fe and Mo are stimulatory. With this supplemented medium growth on 80% H2-20% CO2 is two to three times as great as on 80% N2-20% CO2.

Growth on the yeast extract is very rapid, and i...