Abstract:

Computer vision systems are ideally suited for routine inspection and quality assurance tasks which are common in the food and beverages industries. Backed by powerful machine intelligence and state-of-the-art electronic technologies, machine vision provides a mechanism by which the human thinking process is simulated artificially. Depending on the nature of application and the sensitivity needed to perform the inspection, an image can be acquired at different wavelengths, extending from visible to invisible electromagnetic spectrum. In this chapter the basic electronics needed to acquire an image at three different wavelengths are described. The spectrums covered include the visible, ultrasonic and infrared spectrums. The limitations and drawbacks of each system are also briefly discussed.

1.1 Introduction

In making a physical assessment of agricultural materials and foodstuffs, images are undoubtedly the preferred method for representing concepts to the human brain. Many of the quality factors affecting foodstuffs can be determined by visual inspection and image analysis. Such inspections determine market price and to some extent the ‘best-if-used-before-date’. Traditionally, quality inspection is performed by trained human inspectors who approach the problem of quality assessment in two ways: seeing and feeling. In addition to being costly, this method is highly variable and decisions are not always consistent between inspectors or from day to day. This is, however, changing with the advent of electronic imaging systems and with rapid decline in costs of computers, peripherals and other digital devices. Moreover, the inspection of foodstuffs for various quality factors is a very repetitive task, which is also very subjective in nature. In this type of environment machine vision systems are ideally suited for routine inspection and quality assurance tasks. Backed by powerful artificial intelligence systems and the state-of-the-art electronic technologies, machine vision provides a mechanism in which the human thinking process is simulated artificially. To-date machine vision has extensively been applied to solve various food engineering problems, ranging from simple quality evaluation of food products to complicated robot guidance applications (Abdullah et al., 2000; Pearson, 1996; Tao et al., 1995). Despite the general utility of machine vision images as a first-line inspection tool, their capabilities for more in-depth investigation are fundamentally limited. This is due to the fact that images produced by vision camera are formed using a narrow band of radiation, extending from 10− 4 m to 10− 7 m in wavelength. Due to this, scientists and engineers have invented camera systems that allow patterns of energy from virtually any part of the electromagnetic spectrum to be visualized. Camera systems such as computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and positron emission tomography (PET) operate at shorter wavelengths ranging from 10− 8 m to 10− 13 m. The details are covered in Chapter 3. On the opposite side of the electromagnetic spectrum, there are infrared (IR) and radio cameras which enable visualization to be performed at wavelengths greater than 103 m and 106 m, respectively. All these imaging modalities rely on acquisition hardware featuring an array or ring of detectors which measure the strength of some form of radiation, either due to reflection or after the signal has passed transversely through the object. Perhaps one thing that these camera systems have in common is the requirement to perform digital image processing of the resulting signals using modern computing power. While digital image processing is usually assumed to be the process of converting radiant energy in three-dimensional (3-D) world into a two-dimensional (2-D) radiant array of numbers, this is certainly not so when the detected energy is outside the visible part of the spectrum. The reason is that the technology used to acquire the imaging signals are quite different depending on the camera modalities. The aim of this chapter is, therefore, to give a brief review of the present state-of-the-art of image acquisition technologies which have found many applications in the food industry.

Section 1.2 summarizes the electromagnetic spectrum which is useful in image formation. Section 1.3 includes a summary of the principle of operation of the machine vision technology, followed by illumination and electronics requirements. Other imaging modalities, particularly the acquisition technologies operating at the non-visible range are also briefly discussed. In particular, technologies based on ultrasound and IR are addressed, followed by some of their successful applications in food engineering found in literatures. Section 1.4, which is the final conclusions section, addresses likely future developments in this exciting field of electronic imaging.

1.2 The electromagnetic spectrum

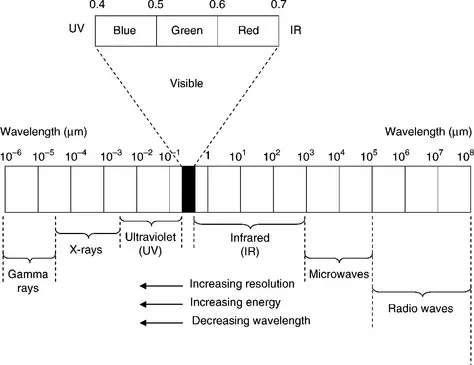

As discussed earlier, images are derived from the electromagnetic radiation in both visible and non-visible range. Radiation energy travels in space at the speed of light, in the form of sinusoidal waves with known wavelengths. Arranged from shorter to longer wavelengths, the electromagnetic spectrum provides information on frequency as well as energy distributions of the electromagnetic radiation. Figure 1.1 gives the electromagnetic spectrum of all electromagnetic waves.

Fig. 1.1 The electromagnetic spectrum comprising the visible and non-visible range.

Referring to Fig. 1.1, the gamma rays with wavelengths less than 0.1 nm constitute the shortest wavelengths of the electromagnetic spectrum. Traditionally, gamma radiation is important for medical and astronomical imaging, leading to the development of various types of anatomical imaging modalities such as the CT, MRI, SPECT and PET. In CT the radiation is projected into the target from diametrically opposed source, while with others it originates from the target – by simulated emission in the case of MRI and through the use of radio-pharmaceuticals in SPECT and PET. On the other hand, the longest waves are radiowaves, which have wavelengths of many kilometres. The well-known ground-probing radar (GPR) and other microwave-based imaging modalities operate in this frequency range. Located in the middle of the electromagnetic spectrum is the visible range, consisting of a narrow portion of the spectrum, from 400 nm (blue) to 700 nm (red). The popular charge coupled device (CCD) camera operates in this spectrum range. IR light lies between the visible and microwave portions of the electromagnetic band. Just like the visible light, IR has wavelengths that range from near (shorter) IR to far (longer) IR. The latter belongs to the thermally sensitive region which makes it useful in imaging applications that rely on heat signature. One example of such an imaging device is the indium–gallium–arsenide (InGaAs)-based near infrared (NIR) camera which gives optimum response from the 900 nm to 1700 nm band (Doebelin, 1996). Ultraviolet (UV) has shorter wavelength than visible light. Similar to IR...