- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Animal Vigilance builds on the author's previous publication with Academic Press (Social Predation: How Group Living Benefits Predators and Prey) by developing several other themes including the development and mechanisms underlying vigilance, as well as developing more fully the evolution and function of vigilance.

Animal vigilance has been at the forefront of research on animal behavior for many years, but no comprehensive review of this topic has existed. Students of animal behavior have focused on many aspects of animal vigilance, from models of its adaptive value to empirical research in the laboratory and in the field. The vast literature on vigilance is widely dispersed with often little contact between models and empirical work and between researchers focusing on different taxa such as birds and mammals. Animal Vigilance fills this gap in the available material.

- Tackles vigilance from all angles, theoretical and empirical, while including the broadest range of species to underscore unifying themes

- Discusses several newer developments in the area, such as vigilance copying and effect of food density

- Highlights recent challenges to assumptions of traditional models of vigilance, such as the assumption that vigilance is independent among group members, which is reviewed during discussion of synchronization and coordination of vigilance in a group

- Written by a top expert in animal vigilance

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Animal Vigilance by Guy Beauchamp in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Ecology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Overview of Animal Vigilance

Abstract

I present an overview of animal vigilance research. First, I tackle the definition of vigilance in animals and then discuss various types of vigilance including a distinction between reactive and proactive vigilance and between vigilance aimed at predators (anti-predator vigilance) and competitors (social vigilance). Using text mining of vigilance references, I present research themes that have emerged over the years. I provide a brief history of vigilance research from its beginnings 100 years ago to the present.

Keywords

anti-predator vigilance

social vigilance

pre-emptive vigilance

reactive vigilance

marker

state

history

1.1. Introduction

Victorian England produced its fair share of famous polymaths. Chief amongst them is Francis Galton (1822–1911) who made seminal contributions to fields of research as varied as psychology, meteorology, and genetics. Better known for the development of eugenics, the improvement of the human race by selective breeding, he also made several long-standing contributions in less controversial fields (Brookes, 2003). Buried in his massive output, there is a record of a trip to present-day Namibia during which he observed the behaviour of free-ranging Damara cattle. While he was primarily interested in understanding the slavish attitudes of men, which we know today as instincts, he was also drawn to social animals, such as the ox, to better understand the gregarious instinct (Galton, 1883). At the time of his research, African lions often ambushed grazing Damara cattle. Galton made the following observations on the cattle:

When he is alone it is not simply that he is too defenceless, but that he is easily surprised. …cattle are obliged in their ordinary course of life to spend a considerable part of the day with their heads buried in the grass, where they can neither see nor smell what is about them. …But a herd of such animals, when considered as a whole, is always on the alert; at almost every moment some eyes, ears, and noses will command all approaches, and the start or cry of alarm of a single beast is a signal to all his companions. …The protective senses of each individual who chooses to live in companionship are multiplied by a large factor, and he thereby receives a maximum of security at a minimum cost of restlessness.

As would be expected from a cousin of Charles Darwin, the father of natural selection, Galton later concluded that there is little doubt that gregariousness in cattle evolved to reduce predation risk.

This excerpt clearly illustrates several key concepts in the study of animal vigilance. Animals use various senses to monitor their surroundings for potential threats, such as ambushing lions in the case of cattle. The purpose of such monitoring is the early detection of threats. Upon detection, conspicuous signals like alarm calls warn all group members about an impending attack. Such signals allow individuals to benefit from all the eyes and ears available in the group to detect threats, making it possible for group members to reduce their own vigilance at no increased risk to themselves. These concepts will be explored more fully in the following chapters.

The original account of the Damara cattle story was published earlier in a relatively obscure magazine article (Galton, 1871). However, the above excerpt was part of a widely cited book on human faculty and development. It is quite surprising that early students of animal vigilance apparently ignored this work. I could only find one citation to Galton’s story buried in a book on animal aggregation (Allee, 1931). It was not until the early 1970s that the work was mentioned again (Hamilton, 1971), a time when the study of animal vigilance picked up in earnest. It is perhaps the case that the message fell on deaf ears.

Ever since the 1970s, vigilance has been recognized as a major component of anti-predator behaviour. In the sequence of events leading to the eventual capture of a prey animal by a predator, vigilance plays a role in the early stages (Endler, 1991). In yet earlier stages, prey can reduce encounters with a predator by being more difficult to locate with adaptations like crypsis or aggregation (Krause and Ruxton, 2002). In later stages, prey animals can reduce the probability of capture following the launch of an attack by adopting defensive formations or confusing the predator. Vigilance plays a role in between these stages by reducing the probability that the predator remains undetected until it is too late to escape successfully. Aimed at predation threats, vigilance can be viewed as a pre-emptive measure to reduce the risk of attack because a detected predator is less likely to pursue the attack (Caro, 2005). Vigilance can also be aimed at conspecifics; in this case, it also serves a pre-emptive role by preventing or avoiding encounters with threatening individuals.

In this chapter, I lay the foundation for the scientific study of animal vigilance. First, I will provide a definition of vigilance and then pinpoint landmark studies, stretching from the pioneering work of Galton to the more recent theoretical and empirical work. I then explore research themes associated with the modern study of animal vigilance.

1.2. Definition and measurements

1.2.1. How to Define Vigilance

In the Oxford dictionary, vigilance is defined as the action or state of keeping careful watch for possible danger or difficulties. The Damara cattle in the Galton story, using their eyes, ears, and noses to detect ambushing lions, are clearly vigilant according to this definition. To add a biological twist to the definition, one can replace ‘careful watch for possible danger’ by ‘monitoring the surroundings for potential threats’, whose nature will be explored later in this section. While the term ‘careful watch’ conjures the idea that vigilance is carried out visually, the term ‘monitoring’ implies that all senses can be used for detection, as the cattle example illustrated.

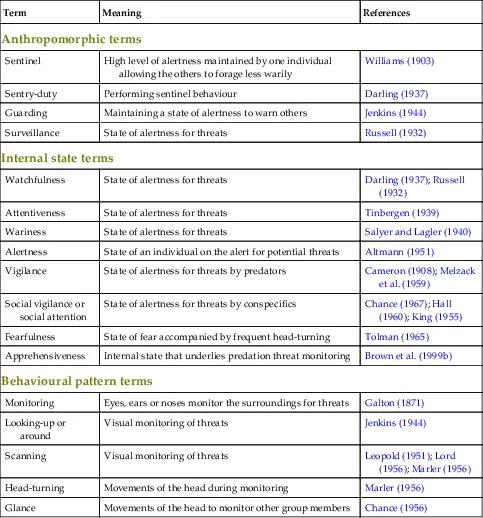

A key feature of the definition is that vigilance can be viewed as a state or behaviour. The state of vigilance, being a predisposition of the brain, cannot be observed directly, but the outward signs, in terms of behaviour, can be observed and measured. I refer to these outward signs of a vigilant state as markers of vigilance. The dichotomy in the definition is reflected by the terms variously used over the years to describe vigilance (Table 1.1). Labels such as watchfulness, wariness, attentiveness and apprehension certainly refer to an internal state that governs how an animal monitors the surroundings for danger. Other labels describe the ways animals actually monitor their surroundings, and fall in the marker family. Terms such as head-turning, scanning, and sniffing convey the observable ways animals use their senses to detect threats. Early researchers described vigilance using terms that are now considered anthropomorphic, such as guarding and sentry-duty, which give the impression that individuals have been assigned a duty by a third party for the benefit of the group. Such terms are avoided nowadays.

Table 1.1

A Lexicon of Vigilance Terms

| Term | Meaning | References |

| Anthropomorphic terms | ||

| Sentinel | High level of alertness maintained by one individual allowing the others to forage less warily | Williams (1903) |

| Sentry-duty | Performing sentinel behaviour | Darling (1937) |

| Guarding | Maintaining a state of alertness to warn others | Jenkins (1944) |

| Surveillance | State of alertness for threats | Russell (1932) |

| Internal state terms | ||

| Watchfulness | State of alertness for threats | Darling (1937); Russell (1932) |

| Attentiveness | State of alertness for threats | Tinbergen (1939) |

| Wariness | State of alertness for threats | Salyer and Lagler (1940) |

| Alertness | State of an individual on the alert for potential threats | Altmann (1951) |

| Vigilance | State of alertness for threats by predators | Cameron (1908); Melzack et al. (1959) |

| Social vigilance or social attention | State of alertness for threats by conspecifics | Chance (1967); Hall (1960); King (1955) |

| Fearfulness | State of fear accompanied by frequent head-turning | Tolman (1965) |

| Apprehensiveness | Internal state that underlies predation threat monitoring | Brown et al. (1999b) |

| Behavioural pattern terms | ||

| Monitoring | Eyes, ears or noses monitor the surroundings for threats | Galton (1871) |

| Looking-up or around | Visual monitoring of threats | Jenkins (1944) |

| Scanning | Visual monitoring of threats | Leopold (1951); Lord (1956); Marler (1956) |

| Head-turning | Movements of the head during monitoring | Marler (1956) |

| Glance | Movements of the head to monitor other group members | Chance (1956) |

In the first review on animal vigilance, vigilance was defined operationally as the probability that an animal will detect a given stimulus at a given time (Dimond and Lazarus, 1974). This definition was clearly influenced by operations research, whose goal is to study how human subjects detect important stimuli in their environment (Davies and Parasuraman, 1982). While this more psychological approach to vigilance can allow us to understand the mechanisms underlying threat detection, the emphasis on the outcome of vigilance, namely, the detection, rather than the means to achieve detection, which we can measure, makes it difficult to apply in the field.

Using the operational definition of vigilance would, however, solve the problem of actually finding a marker of vigilance because...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Overview of Animal Vigilance

- Chapter 2: Function of Animal Vigilance

- Chapter 3: Causation, Development and Evolution of Animal Vigilance

- Chapter 4: Drivers of Animal Vigilance

- Chapter 5: Animal Vigilance and Group Size: Theory

- Chapter 6: Animal Vigilance and Group Size: Empirical Findings

- Chapter 7: Synchronization and Coordination of Animal Vigilance

- Chapter 8: Applied Vigilance

- Conclusions

- References

- Subject Index