Abstract:

Turning is the most common machining operation carried out in any machine shop, thus, knowledge of how to improve this is beneficial in a wide variety of practical applications. This chapter presents the most essential features of turning in order to help shop engineers and specialists to select the right tool, to adjust the machining regime, to avoid vibrations, and to improve the machining quality. For reasons of space, this chapter presents only those basics of turning needed to serve the stated objectives while the relevant references are provided for the well-known and thus widely available information on the matter.

1.1 Introduction

Many industrial seminars, promotion materials, industrial drives and even papers in scientific journals concentrate on advanced turning techniques, such as high-speed turning, hard turning, minimum quantity lubricant or near dry turning, or ultra-precision turning of advanced work materials. Thus it seems that all the problems with traditional turning techniques have been solved and no further research and development will be necessary. Many colorful catalogs of leading tool manufacturers with high-quality realistic pictures enhance this notion even further, creating an impression that all one has to do is select the best tool and machining conditions for a given application, and just follow a few very simple well-defined steps.

In this author’s opinion, nothing could be further from the truth. It is true that the permissible turning speeds and feeds have almost doubled over the past decade. This became possible due to significant improvements in the manufacturing quality of the tools, including the quality of their components (carbides, coatings, etc.), the implementation of better turning machines equipped with advanced controllers as well as their proper maintenance, the application of better coolants, the improved training of engineers and operators, and many other factors. However, actual tool performance and process efficiency (the cost per part) vary significantly from one application to another, from one manufacturing plant to the next, depending on an overwhelming number of variables. Optimum performance in turning is achieved when the combination of the cutting speed (rpm), feed, tool geometry, carbide grade, including its coating, and coolant parameters, have been properly selected, depending upon the work material (its hardness, composition and metallurgical structure), the machine conditions, and the quality requirements of the machined parts. To get the most out of a turning job, one must consider the complete machining system, which includes everything related to the operation. Such consideration is known as the system engineering approach, according to which the machining system should be distinguished and analyzed for the coherence of its components.

This chapter aims to present the most essential features of turning in order to help shop engineers and specialists select the right tool, adjust the machining regime, avoid vibrations, and improve the machining quality. To keep the text within a reasonable limit, this chapter presents only those basics of turning needed to serve the stated objectives while the relevant references are provided for the well-known and thus widely available information on the matter.

1.2 Basic motions

To perform machining operations, relative motion is required between the tool and the workpiece. This relative motion is achieved in most machining operations and is a combined motion consisting of several elementary motions, such as the primary motion, called the cutting speed, and the secondary motion, called the cutting feed. The tool geometry and tool setting relative to the workpiece, combined with these motions, produce the desired shape of the machined surface.

Turning is a general term for a group of machining operations in which the workpiece carries out the prime rotary motion while the tool performs the feed motion. This combination of motions is used for the external and internal turning of surfaces. The basic motions required by turning are provided by a machine tool known as a lathe. The earliest illustration of a lathe is from a well-known Egyptian wall relief carved in stone in the tomb of Petosiris, dating from 300 BC. That is why the lathe is considered the oldest machine tool. The design of the lathe has evolved over centuries. Modern CNC lathes, equipped with powerful motors and high-precision drives, are controlled electronically via a computer menu style interface, the program may be modified and displayed on the machine, along with a simulated view of the process.

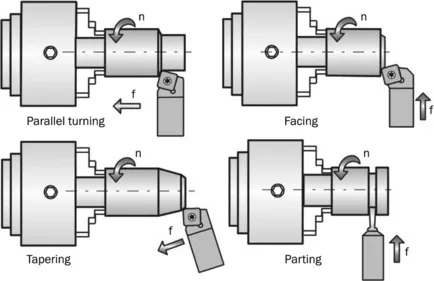

Turning is used for machining cylindrical surfaces. The basic motions of turning are shown in Figure 1.1. They are:

Figure 1.1 Basic motions in turning operations

The primary motion is the rotary motion of the workpiece around the turning axis.

The secondary motion is the translational motion of the tool, known as the feed motion.

Basic turning operations shown in Figure 1.1 differ by the direction of the feed motion with respect to the turning axis and the shape of the tool. In parallel turning (also known as longitudinal turning), the feed direction is parallel to the turning axis. In facing and parting, the feed direction is perpendicu...