- 138 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

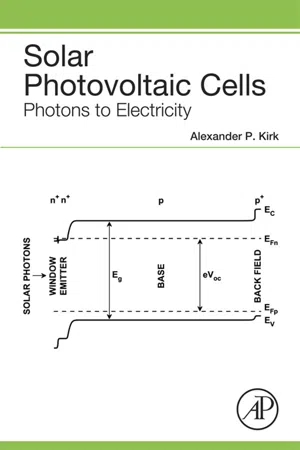

Solar Photovoltaic Cells: Photons to Electricity outlines our need for photovoltaics - a field which is exploding in popularity and importance. This concise book provides a thorough understanding of solar photovoltaic cells including how these devices work, what can be done to optimize the technology, and future trends in the marketplace. This book contains a detailed and logical step-by-step explanation of thermodynamically-consistent solar cell operating physics, a comparison of advanced multi-junction CPV power plants versus combined-cycle thermal power plants in the framework of energy cascading, and a discussion of solar cell semiconductor resource limitations and the scalability of solar electricity as we move forward. Quantitative examples allow the reader to understand the scope of solar PV and the challenges and opportunities of producing clean electricity.

- Provides a compact and focused discussion of solar photovoltaics and solar electricity generation.

- Helps you understand the limits of solar PV and be able to predict future trends.

- Quantitative examples help you grasp the scope of solar PV and the challenges and opportunities of producing electricity from a renewable resource.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Solar Photovoltaic Cells by Alexander P. Kirk in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Engineering General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Energy Demand and Solar Electricity

Abstract

The natural connection we humans already have with sunlight in our daily lives is presented in Chapter 1 where we consider how much energy we demand not just to remain alive but also to live life in our increasingly technology-dense societies. From this, the electricity demand in the USA and also globally is examined, and the amount of electricity generated from photovoltaic modules is compared to other electricity generation technologies such as coal-fired power plants and wind turbines.

Keywords

sunlight

energy

electricity demand

solar electricity

1.1. Introduction

This chapter begins with the connection between humans on Earth and the Sun that we depend on, and must adapt to, in order to survive. Then, we quantify how much energy is needed on average to sustain human life. This human energy demand is used as a benchmark when we next investigate electricity generation in the USA followed by global electricity generation. Solar electricity generation is compared with other electricity generation sources such as wind, natural gas, and coal.

1.2. Human-sunlight connection

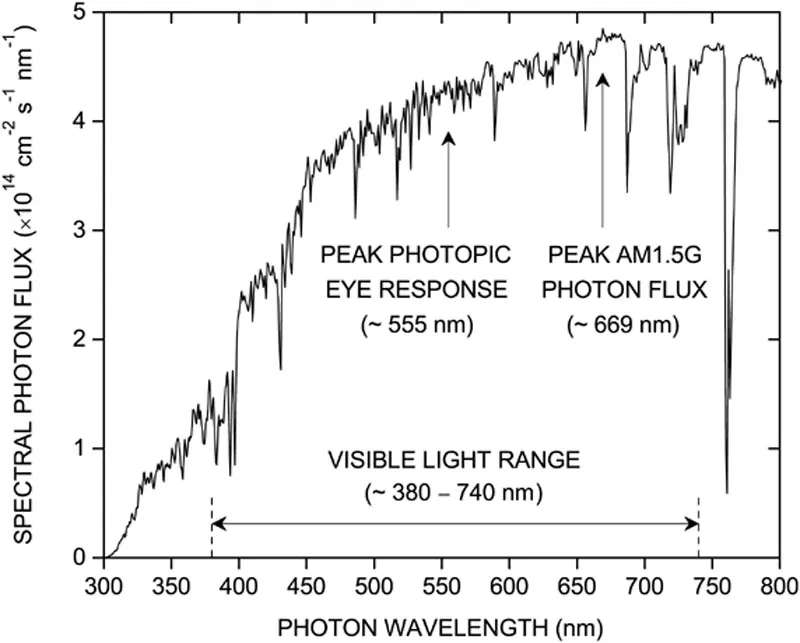

The remarkable human eye contains photoreceptor cone cells that respond to the visible portion of the solar spectrum from ∼380 nm violet light to ∼740 nm red light with photopic (i.e., bright light) vision peak sensitivity corresponding to ∼555 nm green light [1], as shown in Figure 1.1. The near-ultraviolet light that is not absorbed by atmospheric ozone is used by our skin to synthesize vitamin D.

Fig. 1.1 Peak photopic eye response with respect to AM1.5G photon flux and visible light. Note: the AM1.5G terrestrial solar spectrum (developed by Gueymard) and solar photon flux will be described in Chapter 2.

Meanwhile, oxygenic photosynthetic land plants (via chlorophyll and carotenoid molecules) effectively use visible light from the Sun to produce carbohydrate and perhaps the most benign of all waste products – pure oxygen that we breathe. The overall oxygenic photosynthesis process may be expressed by the chemical reaction given by H2O + CO2 → O2 + CH2O, where H2O is water, CO2 is carbon dioxide, O2 is oxygen, and CH2O is used here to represent a generic carbohydrate subunit.

Sunlight-dependent plants provide us plant-dependent humans with the food (carbohydrate) and oxygen that we need to survive and thrive. Plants provide us with clothing (e.g., cotton and linen), shelter for us (e.g., framing material from pine or thatched roofs from straw) and habitat for other animals, shade, furniture, cabinetry, decking and flooring, shipping crates, medicines and homeopathic remedies, paper and cardboard products such as books and boxes, dyes and pigments, perfumes and fragrances, cooking oils, delicious beverages such as tea and coffee, a sink for carbon dioxide, filtration of airborne pollutants, mitigation of soil erosion, coastal storm surge buffering, sound damping, wind breaks, sports fields, and simply enjoyment in our gardens, parks, and nature preserves.

Moreover, the Sun provides warmth, keeps in operation the hydrologic cycle (evaporation of water and precipitation), and in large measure dictates the Earth’s seasonal climate and weather that we must respond and adapt to. Humans even tailor their accessories to enable functionality in sunlight, for example, by using sunglasses and hats or by designing clothing for sunny days such as colorful women’s sundresses. With our natural connection to the Sun and solar radiant energy, it is inherently logical for humans to use sunlight for the purpose of generating clean electricity through the application of solar photovoltaic cells.

1.3. Human energy requirement

Each day, considering an average value, humans require ∼2.33 kWh (kilowatt–hours) of chemical energy to live a healthy life. Typically, instead of the units of kWh, this is expressed (in the USA) on food packaging labels as kcal (kilocalories) where 2.33 kWh is about equal to 2000 kcal [2]. Therefore, each month, on an average, humans require ∼70 kWh of energy. And, in one year, this equates to ∼850 kWh. Stated another way, powering a 100 W light bulb 24 h a day requires about the same energy as the human body each day. With ∼7.1 × 109 humans on the Earth in 2013 [3]; this is nearly equivalent to continually operating a quantity of 7.1 × 109 of the 100 W light bulbs, which results in a yearly energy expenditure of ∼6 × 1012 kWh or 6 PWh (petawatt–hours). Next, we will compare the demand for (chemical) energy that is required simply to power our bodies and sustain our lives to the demand for electricity that we then use to enrich our lives in technology-dense societies such as the USA.

1.4. Electricity generation in the USA

In 2013, total net generation of electricity (“all sectors”) in the USA was ∼4.06 × 1012 kWh [4]. At the end of 2013, the population of the USA was ∼3.17 × 108 [5]. If we normalize electricity consumption in the year 2013 by the population, we find that this leads to an equivalent of ∼1.3 × 104 kWh per year of electricity per person to power the USA and run its economy. This means that ∼35 kWh per day per person of electricity was utilized on an average, or ∼15× more energy per day than it takes just to sustain a human body in a state of good health (∼2.33 kWh per day) as we found in the preceding section. Therefore, on the one hand, while we need a sustainable agricultural base just to maintain human life by providing enough food (chemical energy), on the other hand, we see that living in a technology-dense society requires much more energy if we want to power industrial machinery and processes, run air conditioners and heat pumps, operate computers and charge mobile phone batteries, turn on the lights, and so forth.

Most of our electricity comes from thermal power plants that require either the combustion of fossil fuels or fission of radioactive materials. Specifically, the heat from combustion of coal or fission of uranium is used to convert water into steam; the steam is expanded in a steam turbine that in turn is connect...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Energy Demand and Solar Electricity

- Chapter 2: From Nuclear Fusion to Sunlight

- Chapter 3: Device Operation

- Chapter 4: Energy Cascading

- Chapter 5: Resource Demands and PV Integration

- Chapter 6: Image Gallery

- Note on Technical Content Evolution

- Final Remarks

- Appendix A: List of Symbols

- Appendix B: Abbreviations and Acronyms

- Appendix C: Physical Constants

- Appendix D: Conversion Factors

- Appendix E: Derivation of Absorption Coefficient

- Appendix F: Derivation of Open Circuit Voltage

- Appendix G: Relative Efficiency Ratio

- Appendix H: Recalibrating the Orthodoxy