![]()

Chapter One

What is Professionalism?

The practice of medicine is an art, not a trade; a calling, not a business; a calling in which your heart will be exercised equally with your head.

Osler, 1932, p. 3681

Professionalism, to paraphrase Shakespeare’s Hamlet, is often noted more in the breach than in the observance. When trainees in health-care professions are asked to define professionalism, they tend to describe examples of lack of professionalism: clinicians who mistreat patients or colleagues, who put their own needs ahead of the team or the patient, who lack competence but refuse to acknowledge their limitations, and whose approach to clinical care lacks the compassion and empathy that Osler so eloquently described when he called medicine “a calling in which your heart will be exercised equally with your head” (DeJong, 2010–12). Sometimes these deficits are glaringly obvious, such as the surgeon who left the operating room to go to cash a paycheck, leaving the patient on the table (Swidey, 2004). Other times they are more implicit, only inferable by overly casual dress, sloppy documentation, poor time management, inappropriate tone of voice.

How professionalism is manifested and perceived may vary by developmental stage, gender, and geographic, ethnic and institutional cultures. Some evidence suggests that women value professionalism more than men (Roberts, Warner, Hammond, Geppert & Heinrich, 2005). Some studies suggest that views of professionalism shift over the developmental trajectory of practitioners’ careers in health care (Nath, Schmidt & Gunel, 2006; Wagner, Hendrich, Moseley & Hudson, 2007). What is considered professional in one health-care environment may not be in another: Jeans, open-toed shoes, and low-cut blouses may be acceptable at some institutions in some parts of the world, and within some specialties, but not in others. And culture can change over time: While scrubs used to be prohibited outside the hospital in the United States, they have now become commonplace.

But professional presentation and etiquette are not a substitute for fundamental professional attributes; the latter go deeper to the level of moral judgment, ethics, integrity, and altruism, to what Hafferty has called “the professional self”:

Taking on the identity of a true medical professional… involves a number of value orientations, including a general commitment not only to learning and excellent of skills but also to behavior and practice that are authentically caring… There is a meaningful (and measurable) difference between being a professional and acting professionally.

Hafferty, 2006, p. 2152

The relationship between patient and health-care professional carries a “fiduciary duty”: The professional has an obligation to act for the patient’s benefit and the patient places ultimate faith in the abilities and good intentions of the professional. Professionalism is the foundation for the trust patients place in their caregivers. When that trust is broken, patients rightfully protest: Breaches of professionalism are a common cause for patient complaints and for negative media reports about health-care professionals (Hickson et al., 2002). In one retrospective study, physicians who were disciplined by state licensing boards were three times more likely to have shown unprofessional behavior in medical school than were those with no such disciplinary actions (Papadakis et al., 2005).

Health care has come under closer scrutiny in recent years as professionalism has been challenged by changes in health-care delivery, growing expectations by the public, the increasing role of corporate entities, and technology. The American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) began its Project Humanism in the 1980s and its Project Professionalism in the 1990s. Guidelines for medical schools and certification standards require demonstrated professionalism at the undergraduate and graduate level (Association of American Medical Colleges, Institute for International Medical Education, American Council for Graduate Medical Education; see Rider, 2007, p. 189). Given these requirements, efforts have been underway to try to define and assess professionalism.

In the United States, the definition of professionalism has focused more on the attributes of clinicians and their capacity to self-monitor, self-reflect, and self-regulate. Qualities such as compassion, competence, integrity, consistency, commitment, altruism, leadership, and insight come to mind (Rider, 2007). In this model, professional clinicians are those who are constantly assessing their clinical and technical skills and trying to improve; taking care of patients from the standpoint of values of humanism and empathy; shunning self-interest to focus on the care of others.

Closely related, but with a somewhat different emphasis, is the “patient-centered” professionalism model (Irvine, 2005). Writing in the UK, Irvine emphasizes the expertise of the clinician (knowledge base and skill set); the adherence to ethical virtues of beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy, and justice; and the service to the patient. This model reinforces the importance of developing a patient-centered health-care culture, and of a regulatory system to assess and monitor clinicians’ expertise, since patients themselves are unable to do so. Implicit in this model is the notion that health-care providers should be truthful and open with their patients, and maintain patient confidentiality; they should provide patients with information so that they can make informed decisions with their providers about their care; they should acknowledge their own limitations of professional competence; and they should be respectful and unbiased towards the patient’s individual and cultural values.

As Irvine’s model makes clear, professionalism is often closely associated with ethics, which are typically delineated in professional codes such as the American Medical Association’s code of ethics (http://bit.ly/kaaxBG). American psychiatrists Glen Gabbard and Laura Roberts have pointed out that “professionalism is embodied in ethical action” (Gabbard et al., 2012, p. 17). They emphasize the key role of biomedical ethics concepts in professional behavior (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1

Important Principles of Medical Ethics1

| Altruism | Acting for the good of others, without self-interest and at times requiring self-sacrifice |

| Autonomy | Being able to deliberate and make reasoned decisions for one’s self and to act on the basis of such decisions; literally “self-rule” |

| Beneficence | Seeking to bring about good or benefit |

| Compassion | Literally, “suffering with” another person, with kindness and an active regard for his or her welfare; more closely related to empathy than to sympathy, as the latter connotes the more distanced experience of “feeling sorry for” the individual |

| Confidentiality | Upholding the obligation not to disclose information obtained from patients or observed about them without their permission; a privilege linked to the legal right of privacy that may at times be overridden by exceptions stipulated by law |

| Fidelity | Keeping promises, being truthful, and being honorable; in clinical care, the faithfulness with which a clinician commits to the duty of helping patients and acting in a manner that is in keeping with the ideals of the profession |

| Honesty | Conveying the truth fully, without misrepresentation through deceit, bias or omission |

| Integrity | Maintaining professional soundness and reliability of intention and action; a virtue literally defined as wholeness or coherence |

| Justice | Ensuring fairness; distributive justice refers to the fair and equitable distribution of resources and burden through society |

| Nonmaleficence | Avoiding doing harm |

| Respect for persons | Fully regarding and according intrinsic value to someone or something; reflected in treating another individual with genuine consideration and attentiveness to that person’s life history, values and goals |

| Respect for the law | Acting in accordance with the laws of society |

| Voluntarism | Maintaining a belief or acting from one’s own free will and ensuring that the belief or action is not coerced or unduly influenced by others |

1Gabbard , G. O., Roberts, L. W., Crisp-Han, H., Ball, V., Hobday, G., & Rachal, F. (2012). Professionalism in Psychiatry (pp. 21–22). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

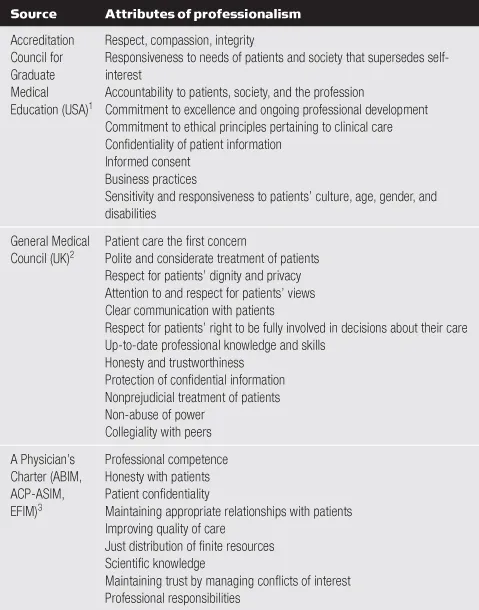

In 2002, ABIM, the American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine (ACP-ASIM), and the European Federation of Internal Medicine jointly published a document entitled, “Medical professionalism in the new millennium: A physician charter.” The charter, based in part on the work of physicians Sylvia and Richard Cruess at McGill University in Canada, takes professionalism one step further to encompass not only relationships with patients, but also relationships with our students, colleagues, and society as a whole (Cruess, Johnston & Cruess, 2002). The writers argue that physicians (and arguably all health-care providers) are both healers and professionals, and that a “social contract” exists between physicians and society. This charter embodies three fundamental principles: the primacy of patient welfare; patient autonomy; and social justice. It entails ten professional responsibilities to which physicians should commit: professional competence; honesty with patients; patient confidentiality; maintaining appropriate relations with patients; improving quality of care; improving access to care; just distribution of finite resources; scientific knowledge; maintaining trust by managing conflicts of interest; and a commitment to these responsibilities (ABIM Foundation et al., 2002). This description of professionalism takes health-care professionals way beyond the treatment room, out into society as a whole where they have an important leadership role in advocating for quality and access, and equitable resource allocation (Table 1.2).

Table 1.2

Professionalism Attributes

1www.acgme.org/outcome/comp/compFull.asp

2www.gmc-uk.org/guidance/archive/library/duties_of_a_doctor.asp

3www.abimfoundation.org/professionalism/pdf_charter/ABIM_Charter_Ins.pdf

How do health-care professionals get into trouble with unprofessional behavior? Examples of unprofessional behavior reported by those who teach medical students and residents include dishonesty (both intellectual and personal); being arrogant, disrespectful or abrasive to the patient, students, or coworkers; failing to take responsibility for errors and/or not being fully invested in the clinical outcome of the patient; conflict of interest and financial gain, such as accepting kickbacks when ordering certain treatments; failure to stay up to date in clinical care; and engaging in high-risk behaviors, such as substance abuse and sexual misconduct (Duff, 2004).

While such examples clearly represent a dearth of the professionalism described in the three models above (the individual and “self-reflection,” the “patient-centered,” and the “social contract” models; Table 1.3), many can also be described as transgressions of implicit or explicit boundaries. The concept of boundaries implies a border or limit. Boundary violations occur when such borders or limits are crossed inappropriately, causing real or potential harm to others. Boundary crossings take place when the boundary is crossed but without frank harm. Sometimes, the boundary is not so clearly crossed, but rather made permeable, le...