- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Welded design is often considered as an area in which there's lots of practice but little theory. Welded design tends to be overlooked in engineering courses and many engineering students and engineers find materials and metallurgy complicated subjects. Engineering decisions at the design stage need to take account of the properties of a material – if these decisions are wrong failures and even catastrophes can result. Many engineering catastrophes have their origins in the use of irrelevant or invalid methods of analysis, incomplete information or the lack of understanding of material behaviour.The activity of engineering design calls on the knowledge of a variety of engineering disciplines. With his wide engineering background and accumulated knowledge, John Hicks is able to show how a skilled engineer may use materials in an effective and economic way and make decisions on the need for the positioning of joints, be they permanent or temporary, between similar and dissimilar materials.This book provides practising engineers, teachers and students with the necessary background to welding processes and methods of design employed in welded fabrication. It explains how design practices are derived from experimental and theoretical studies to produce practical and economic fabrication.

- Provides specialist information on a topic often omitted from engineering courses

- Explains why certain methods are used, and also gives examples of commonly performed calculations and derivation of data.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

The engineer

Publisher Summary

This chapter focuses on the responsibilities and achievements of an engineer in the field of welding. An engineer’s responsibility to society requires that not only he keeps up to date with the ever faster changing knowledge and practices but also that he recognizes the boundaries of his own knowledge. The engineer devises and makes structures and devices to perform duties or achieve results. Most engineering projects require the contributions of a variety of engineering disciplines in a team. One of the members of that team in many products or projects is the welding engineer. The execution of the responsibilities of the welding engineer takes place at the interface of a number of conventional technologies. For contributing to the design of the welded product, these include structural and mechanical engineering, material processing, weldability and performance, and corrosion science. For the setting up and operation of welding plant, they include electrical, mechanical and production engineering, and the physics and chemistry of gases. In addition, the welding engineer must be familiar with the general management of industrial processes and personnel, as well as the health and safety aspects of the welding operations and materials.

1.1 Responsibility of the engineer

As we enter the third millennium annis domini, most of the world’s population continues increasingly to rely on man-made and centralised systems for producing and distributing food and medicines and for converting energy into usable forms. Much of these systems relies on the, often unrecognised, work of engineers. The engineer’s responsibility to society requires that not only does he keep up to date with the ever faster changing knowledge and practices but that he recognises the boundaries of his own knowledge. The engineer devises and makes structures and devices to perform duties or achieve results. In so doing he employs his knowledge of the natural world and the way in which it works as revealed by scientists, and he uses techniques of prediction and simulation developed by mathematicians. He has to know which materials are available to meet the requirements, their physical and chemical characteristics and how they can be fashioned to produce an artefact and what treatment they must be given to enable them to survive the environment.

The motivation and methods of working of the engineer are very different from those of a scientist or mathematician. A scientist makes observations of the natural world, offers hypotheses as to how it works and conducts experiments to test the validity of his hypothesis; thence he tries to derive an explanation of the composition, structure or mode of operation of the object or the mechanism. A mathematician starts from the opposite position and evolves theoretical concepts by means of which he may try to explain the behaviour of the natural world, or the universe whatever that may be held to be. Scientists and the mathematicians both aim to seek the truth without compromise and although they may publish results and conclusions as evidence of their findings their work can never be finished. In contrast the engineer has to achieve a result within a specified time and cost and rarely has the resources or the time to be able to identify and verify every possible piece of information about the environment in which the artefact has to operate or the response of the artefact to that environment. He has to work within a degree of uncertainty, expressed by the probability that the artefact will do what is expected of it at a defined cost and for a specified life. The engineer’s circumstance is perhaps summarised best by the oft quoted request: ‘I don’t want it perfect, I want it Thursday!’ Once the engineer’s work is complete he cannot go back and change it without disproportionate consequences; it is there for all to see and use. The ancient Romans were particularly demanding of their bridge engineers; the engineer’s name had to be carved on a stone in the bridge, not to praise the engineer but to know who to execute if the bridge should collapse in use!

People place their lives in the hands of engineers every day when they travel, an activity associated with which is a predictable probability of being killed or injured by the omissions of their fellow drivers, the mistakes of professional drivers and captains or the failings of the engineers who designed, manufactured and maintained the mode of transport. The engineer’s role is to be seen not only in the vehicle itself, whether that be on land, sea or air, but also in the road, bridge, harbour or airport, and in the navigational aids which abound and now permit a person to know their position to within a few metres over and above a large part of the earth.

Human error is frequently quoted as the reason for a catastrophe and usually means an error on the part of a driver, a mariner or a pilot. Other causes are often lumped under the catch-all category of mechanical failure as if such events were beyond the hand of man; a naïve attribution, if ever there were one, for somewhere down the line people were involved in the conception, design, manufacture and maintenance of the device. It is therefore still human error which caused the problem even if not of those immediately involved. If we need to label the cause of the catastrophe, what we should really do is to place it in one of, say, four categories, all under the heading of human error, which would be failure in specification, design, operation or maintenance. An ‘Act of God’ so beloved by judges is a get-out. It usually means a circumstance or set of circumstances which a designer, operator or legislator ought to have been able to predict and allow for but chose to ignore. If this seems very harsh we have only to look at the number of lives lost in bulk carriers at sea in the past years. There still seems to be a culture in seafaring which accepts that there are unavoidable hazards and which are reflected in the nineteenth century hymn line‘… for those in peril on the sea’. Even today there are cultures in some countries which do not see death or injury by man-made circumstances as preventable or even needing prevention; concepts of risk just do not exist in some places. That is not to say that any activity can be free of hazards; we are exposed to hazards throughout our life. What the engineer should be doing is to conduct activities in such a way that the probability of not surviving that hazard is known and set at an accepted level for the general public, leaving those who wish to indulge in high risk activities to do so on their own.

We place our lives in the hands of engineers in many more ways than these obvious ones. When we use domestic machines such as microwave ovens with their potentially injurious radiation, dishwashers and washing machines with a potentially lethal 240 V supplied to a machine running in water into which the operator can safely put his or her hands. Patients place their lives in the hands of engineers when they submit themselves to surgery requiring the substitution of their bodily functions by machines which temporarily take the place of their hearts, lungs and kidneys. Others survive on permanent replacements for their own bodily parts with man-made implants be they valves, joints or other objects. An eminent heart surgeon said on television recently that heart transplants were simple; although this was perhaps a throwaway remark one has to observe that if it is simple for him, which seems unlikely, it is only so because of developments in immunology, on post-operative critical care and on anaesthesia (not just the old fashioned gas but the whole substitution and maintenance of complete circulatory and pulmonary functions) which enables it to be so and which relies on complex machinery requiring a high level of engineering skill in design, manufacturing and maintenance. We place our livelihoods in the hands of engineers who make machinery whether it be for the factory or the office.

Businesses and individuals rely on telecommunications to communicate with others and for some it would seem that life without television and a mobile telephone would be at best meaningless and at worst intolerable. We rely on an available supply of energy to enable us to use all of this equipment, to keep ourselves warm and to cook our food. It is the engineer who converts the energy contained in and around the Earth and the Sun to produce this supply of usable energy to a remarkable level of reliability and consistency be it in the form of fossil fuels or electricity derived from them or nuclear reactions.

1.2 Achievements of the engineer

The achievements of the engineer during the second half of the twentieth century are perhaps most popularly recognised in the development of digital computers and other electronically based equipment through the exploitation of the discovery of semi-conductors, or transistors as they came to be known. The subsequent growth in the diversity of the use of computers could hardly have been expected to have taken place had we continued to rely on the thermionic valve invented by Sir Alexander Fleming in 1904, let alone the nineteenth century mechanical calculating engine of William Babbage. However let us not forget that at the beginning of the twenty-first century the visual displays of most computers and telecommunications equipment still rely on the technology of thermionic emission. The liquid crystal has occupied a small area of application and the light emitting diode has yet to reach its full potential.

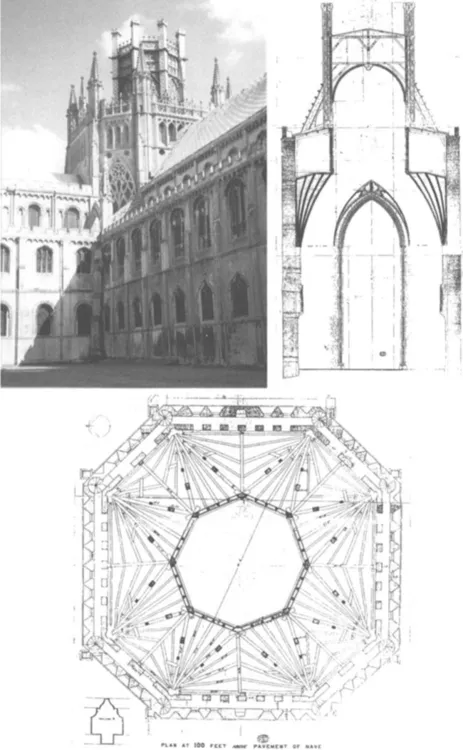

The impact of electronic processing has been felt both in domestic and in business life across the world so that almost everybody can see the effect at first hand. Historically most other engineering achievements probably have had a less immediate and less personal impact than the semi-conductor but have been equally significant to the way in which trade and life in general was conducted. As far as life in the British Isles was concerned this process of accelerating change made possible by the engineer might perhaps have begun with the building of the road system, centrally heated villas and the setting up of industries by the Romans in the first few years AD. However their withdrawal 400 years later was accompanied by the collapse of civilisation in Britain. The invading Angles and Saxons enslaved or drove the indigenous population into the north and west; they plundered the former Roman towns and let them fall into ruin, preferring to live in small self-contained settlements. In other countries the Romans left a greater variety of features; not only roads and villas but mighty structures such as that magnificent aqueduct, the Pont du Gard in the south of France (Fig. 1.1). Hundreds of years were to pass before new types of structures were erected and of these perhaps the greatest were the cathedrals built by the Normans in the north of France and in England. The main structure of these comprised stone arches supported by external buttresses in between which were placed timber beams supporting the roof. Except for these beams all the material was in compression. The modern concept of a structure with separate members in tension, compression and shear which we now call chords, braces, ties, webs, etc. appears in examples such as Ely Cathedral in the east of England. The cathedral’s central tower, built in the fourteenth century, is of an octagonal planform supported on only eight arches. This tower itself supports a timber framed structure called the lantern (Fig. 1.2). However let us not believe that the engineers of those days were always successful; this octagonal tower and lantern at Ely had been built to replace the Norman tower which collapsed in about 1322.

Except perhaps for the draining of the Fens, also in the east of England, which was commenced by the Dutch engineer, Cornelius Vermuyden, under King Charles I in 1630, nothing further in the modern sense of a regional or national infrastructure was developed in Britain until the building of canals in the eighteenth century. These were used for moving bulk materials needed to feed the burgeoning industrial revolution and the motive power was provided by the horse. Canals were followed by, and to a great extent superseded by, the railways of the nineteenth century powered by steam which served to carry both goods and passengers, eventually in numbers, speed and comfort which the roads could not offer. Alongside these came the emergence of the large oceangoing ship, also driven by steam, to serve the international trade in goods of all types. The contribution of the inventors and developers of the steam engine, initially used to pump water from mines, was therefore central to the growth of transport. Amongst them we acknowledge Savory, Newcomen, Trevithick, Watt and Stephenson. Alongside these developments necessarily grew the industries to build the means and to make the equipment for transport and which in turn provided a major reason for the existence of a transport system, namely the production of goods for domestic and, increasingly, overseas consumption.

Today steam is still a major means of transferring energy in both fossil fired and nuclear power stations as well as in large ships using turbines. Its earlier role in smaller stationary plant and in other transport applications was taken over by the internal combustion engine both in its piston and turbine forms. Subsequently the role of the stationary engine has been taken over almost entirely by the electric motor. In the second half of the twentieth century the freight carrying role of the railways became substantially subsumed by road vehicles resulting from the building of motorways and increasing the capacity of existing main roads (regardless of the wider issues of true cost and environmental damage). On a worldwide basis the development and construction of even larger ships for the cheap long distance carriage of bulk materials and of larger aircraft for providing cheap travel for the masses were two other achievements. Their use built up comparatively slowly in the second half of the century but their actual development had taken place not in small increments but in large steps. The motivation for the ship and aircraft changes was different in each case. A major incentive for building larger ships was the closure of the Suez Canal in 1956 so that oil tankers from the Middle East oil fields had to travel around the Cape of Good Hope to reach Europe. The restraint of the canal on vessel size then no longer applied and the economy of scale afforded by large tankers and bulk carriers compensated for the extra distance. The development of a larger civil aircraft was a bold commercial decision by the Boeing Company. Its introduction of the type 747 in the early 1970s immediately increased the passenger load from a maximum of around 150 to something approaching 400. In another direction of development at around the same time British Aerospace (or rather, its predecessors) and Aérospatiale offered airline passengers the first, and so far the only, means of supersonic travel. Alongside these developments were the changes in energy conversion both to nuclear power as well as to larger and more efficient fossil-fuelled power generators. In the last third of the century extraction of oil and gas from deeper oceans led to very rapid advancements in structural steel design and in materials and joining technologies in the 1970s. These advances have spun off into wider fields of structural engineering in which philosophies of structural design addressed more and more in a formal way matters of integrity and economy. In steelwork design generally more rational approaches to probabilities of occurrences of loads and the variability of material properties were considered and introduced. These required a closer attention to questions of quality in the sense of consistency of the product ...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: The engineer

- Chapter 2: Metals

- Chapter 3: Fabrication processses

- Chapter 4: Considerations in designing a welded joint

- Chapter 5: Static strength

- Chapter 6: Fatigue cracking

- Chapter 7: Brittle fracture

- Chapter 8: Structural design

- Chapter 9: Offshore structures

- Chapter 10: Management systems

- Chapter 11: Weld quality

- Chapter 12: Standards

- References

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Welded Design by J Hicks in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Materials Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.