eBook - ePub

Regenerative Medicine and Biomaterials for the Repair of Connective Tissues

- 504 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Regenerative Medicine and Biomaterials for the Repair of Connective Tissues

About this book

Regenerative medicine for the repair of connective tissues is a fast moving field which generates a lot of interest. Unfortunately the biomaterials and biomechanics for soft tissue repair has been under-represented in the past. Particularly the natural association between cartilage, tendons and ligaments is often not made.Regenerative medicine and biomaterials for the repair of connective tissues addresses this gap in the market by bringing together the natural association of cartilage, tendons and ligaments to provide a review of the different structures, biomechanics and, more importantly, provide a clear discussion of practical techniques and biomaterials which may be used to repair the connective tissues.Part one discusses cartilage repair and regeneration with chapters on such topics as structure, biomechanics and repair of cartilage. Chapters in Part two focus on the repair of tendons on ligaments with particular techniques including cell-based therapies for the repair and regeneration of tendons and ligaments and scaffolds for tendon and ligament tissue engineering.

- Addresses the natural association between cartilage, tendons and ligaments which is often not made

- Provides a review of the different structures, biomechanics and practical techniques which are used in the repair of connective tissues

- Chapters focus on such areas as cartilage repair and regeneration, the repair of tendons and ligaments, investigating techniques including scaffolds and cell-based therapies

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Regenerative Medicine and Biomaterials for the Repair of Connective Tissues by Charles Archer,Jim Ralphs in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Tecnología e ingeniería & Tecnología y suministros médicos. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The structure and regenerative capacity of synovial joint tissues

A.-M. Säämänen, University of Turku, Finland

J.P.A. Arokoski, University of Kuopio and Kuopio University Hospital, Finland

J.S. Jurvelin, University of Kuopio, Finland

I. Kiviranta, University of Helsinki, Finland

Abstract:

This chapter provides an introduction to the structure, function, and biomechanical properties of synovial joint and its tissues with special emphasis to articular cartilage. Structural elements are described at the cellular level. Major extracellular matrix components, their organization and relationship with biomechanical properties are described. Also, a short introduction to basic methodology to measure biomechanical parameters is presented. In addition, the studies demonstrating presence of human endogenous multi-potent mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs) and mesenchymal progenitors in synovial joint and associated tissues are reviewed. Possible implications of endogenous MSCs in tissue repair potential are discussed.

Key words

synovial joint

biomechanics

multi-potent mesenchymal stromal cell

tissue regeneration

1.1 Introduction

The purpose of this chapter is to introduce the reader to the structure and function of synovial joint and associated structures. First, the macroscopic structure of synovial joint compartments, cellular composition, tissue organization, and description of the major extracellular components will be reviewed in articular cartilage, subchondral bone, tendon and ligaments, synovial membrane, and meniscus. Second, the interrelationship of extracellular matrix composition with biomechanical properties of the tissues will be discussed. In addition, the basic methodology used for measuring the biomechanical parameters of joint tissues, with emphasis on articular cartilage, will be introduced. Third, the presence of resident mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) and progenitors in synovial joint tissues will be described, and differences in properties of MSCs derived from different intra-articular and extra-articular tissues will be discussed. MSCs represent the intrinsic repair potential in these tissues, but they also have a significant input in regulating tissue homeostasis by secreting several growth factors, cytokines and bioactive factors. The progress of stem cell research during the last ten years has increased our understanding of their function in tissue regeneration. However, knowledge of the role of MSCs in the repair processes of many joints tissues is still deficient.

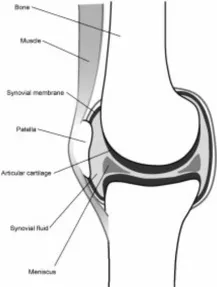

1.2 Structure and function of synovial joint

The synovial joint is a functional unit with mechanically interacting structural components (Fig. 1.1). The development of synovial joints arises from the mesenchymal cells (Archer et al. 2003; Khan et al. 2007). Hyaline cartilage itself forms the cartilaginous model of the developing skeleton. It is replaced by bone in a process known as endochondral ossification (Mackie et al. 2008). Articular cartilage (AC) covers the ends of the bones and synovial fluid lubricates and nourishes the cartilaginous tissue. Ligaments bind the skeletal elements together and a fibrous capsule encapsulates the joint. The synovial joint (e.g. knee joint) may also contain meniscal structures internally. Each joint tissue, including bone, muscle, AC, ligaments, and tendons, has its unique structure and functional properties, and changes in any component may lead to anabolic or catabolic responses in another joint component.

1.1 Schematic presentation of the anatomy of the knee joint. A sagittal view.

The knee joint, joining femur and tibia in the lower limb, is the biggest synovial joint in the body. It consists of three articulating bones (femur, tibia and patella) covered by hyaline cartilage, the quadriceps and hamstring muscles, collateral and cruciate ligaments that hold the joint together, patellar tendon and the menisci. In principle, the knee is constructed of two joints, i.e. the patello-femoral joint and the tibio-femoral joint. The knee joint structures enable compression, rolling and sliding between the contacting bones. Also, the joints transmit loads of the upper body, reaching tibio-femoral loads of eight times the body weight (Kuster et al. 1997) and patello-femoral joint loads seven times the body weight (Nisell 1985) during normal daily activities, such as downhill walking and jogging. Based on the experimental analysis during simulated walking cycle, maximum tibio-femoral contact stresses of 14 MPa were recorded (Thambyah et al. 2005). This could be considered potentially dangerous for AC, knowing that there appears to be a critical threshold stress (15–20 MPa) that causes cell death and rupture of collagen network in vitro (D’Lima et al. 2001; Torzilli et al. 2006). It is suggested that the amount of load-induced cell death is a function of the duration and magnitude of the applied load.

In a healthy synovial joint, the friction coefficient between contacting articular surfaces is low; typical values between 0.01 and 0.04 have been estimated in a human hip (Unsworth et al. 1975). Several lubrication theories have been proposed, including hydrodynamic, squeeze film, and weeping and boosted mechanisms for lubrication. Each of them specifically addresses the role of intrinsic fluid and synovial fluid. Based on the operational demand, more than one lubrication mechanism is needed to provide the low friction within the synovial joint. For lubrication, the highly important mechanism is the interstitial fluid pressurization within the cartilage matrix (Ateshian 2009). However, during static loading, the boundary type of lubrication is facilitated by the molecules such as hyaluronan (HA), glycoproteins, and surface active phospholipids found in the synovial fluid (Katta et al. 2008).

Functional adaptation is known as conditioning of the structure, composition and functional properties of the joint tissues to mechanical loads they are exposed to (Hyttinen et al. 2001; Tammi et al. 1987). In a healthy joint, this will lead to optimized joint function. However, mechanical conditioning may fail, leading to overloading of joint structures and, subsequently, to harmful changes in the tissues. Further, this will create an imbalance between tissue properties and functional demands, leading potentially to progressive degeneration of the structures in question. In osteoarthritis (OA), the pathological process may be triggered by changes in any joint component and no consensus has been found for the initial pathological mechanism. However, mechanical factors have been considered critical in the initiation and progress of OA. Changes in cartilage, such as early superficial depletion of proteoglycans (Arokoski et al. 2000; Helminen et al. 2000) has been considered as a primary mechanism for the OA process, but alternative theories address the role of initial subchondral changes, including bone stiffening (Radin and Rose 1986; Burr and Radin 2003), in the pathological degeneration of cartilage tissue.

1.3 Joint tissues and their biomechanical properties

1.3.1 Articular cartilage

Articular cartilage is highly specialized connective tissue, and it is aneural, alymphatic, and generally considered to be avascular. Its nourishment depends on the synovial fluid and subchondral bone. The thickness of AC varies from some micrometers to a few millimeters in different cartilage areas within the joint, in different joints, and animal species. Biomechanically, the primary function of the AC is to provide a covering material that protects the subchondral bone and provides a smooth, lubricate...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Contributor contact details

- Chapter 1: The structure and regenerative capacity of synovial joint tissues

- Chapter 2: The myofibroblast in connective tissue repair and regeneration

- Part I: Cartilage repair and regeneration

- Part II: Repair of tendons and ligaments

- Index