- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Cyber Attacks takes the national debate on protecting critical infrastructure in an entirely new and fruitful direction. It initiates an intelligent national (and international) dialogue amongst the general technical community around proper methods for reducing national risk. This includes controversial themes such as the deliberate use of deception to trap intruders. It also serves as an attractive framework for a new national strategy for cyber security, something that several Presidential administrations have failed in attempting to create. In addition, nations other than the US might choose to adopt the framework as well.This book covers cyber security policy development for massively complex infrastructure using ten principles derived from experiences in U.S. Federal Government settings and a range of global commercial environments. It provides a unique and provocative philosophy of cyber security that directly contradicts conventional wisdom about info sec for small or enterprise-level systems. It illustrates the use of practical, trial-and-error findings derived from 25 years of hands-on experience protecting critical infrastructure on a daily basis at AT&T. Each principle is presented as a separate security strategy, along with pages of compelling examples that demonstrate use of the principle. Cyber Attacks will be of interest to security professionals tasked with protection of critical infrastructure and with cyber security; CSOs and other top managers; government and military security specialists and policymakers; security managers; and students in cybersecurity and international security programs.

- Covers cyber security policy development for massively complex infrastructure using ten principles derived from experiences in U.S. Federal Government settings and a range of global commercial environments

- Provides a unique and provocative philosophy of cyber security that directly contradicts conventional wisdom about info sec for small or enterprise-level systems

- Illustrates the use of practical, trial-and-error findings derived from 25 years of hands-on experience protecting critical infrastructure on a daily basis at AT&T

Trusted by 375,005 students

Access to over 1 million titles for a fair monthly price.

Study more efficiently using our study tools.

Information

1 Introduction

National infrastructure refers to the delivery and support systems for a nation's large-scale services such as law enforcement databases, military support services, and mobile telecommunications. These services can be supplied directly by the government or by commercial groups. Because much of the national infrastructure is delivered over or controlled via the Internet, it is extremely vulnerable to cyber attacks. Due to the massive size of our national infrastructure and enormous volumes of data involved, well-known computer security techniques may not be applicable. A new protection methodology is needed and must address four diverse security threat types—availability, disclosure, integrity, and theft—from three types of potential malicious adversaries—external adversary, internal adversary, and supplier adversary. A proposed new cyber protection methodology incorporates ten basic design and operation principles—deception, separation, diversity, consistency, depth, discretion, collection, correlation, awareness, and response—and specifically addresses how these principles can be applied to protecting our national infrastructure.

Somewhere in his writings—and I regret having forgotten where—John Von Neumann draws attention to what seemed to him a contrast. He remarked that for simple mechanisms it is often easier to describe how they work than what they do, while for more complicated mechanisms it was usually the other way round.

Edsger W. Dijkstra 1

National infrastructure refers to the complex, underlying delivery and support systems for all large-scale services considered absolutely essential to a nation. These services include emergency response, law enforcement databases, supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) systems, power control networks, military support services, consumer entertainment systems, financial applications, and mobile telecommunications. Some national services are provided directly by government, but most are provided by commercial groups such as Internet service providers, airlines, and banks. In addition, certain services considered essential to one nation might include infrastructure support that is controlled by organizations from another nation. This global interdependency is consistent with the trends referred to collectively by Thomas Friedman as a “flat world.”2

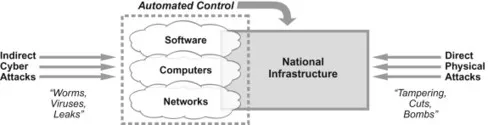

National infrastructure, especially in the United States, has always been vulnerable to malicious physical attacks such as equipment tampering, cable cuts, facility bombing, and asset theft. The events of September 11, 2001, for example, are the most prominent and recent instance of a massive physical attack directed at national infrastructure. During the past couple of decades, however, vast portions of national infrastructure have become reliant on software, computers, and networks. This reliance typically includes remote access, often over the Internet, to the systems that control national services. Adversaries thus can initiate cyber attacks on infrastructure using worms, viruses, leaks, and the like. These attacks indirectly target national infrastructure through their associated automated controls systems (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 National infrastructure cyber and physical attacks.

A seemingly obvious approach to dealing with this national cyber threat would involve the use of well-known computer security techniques. After all, computer security has matured substantially in the past couple of decades, and considerable expertise now exists on how to protect software, computers, and networks. In such a national scheme, safeguards such as firewalls, intrusion detection systems, antivirus software, passwords, scanners, audit trails, and encryption would be directly embedded into infrastructure, just as they are currently in small-scale environments. These national security systems would be connected to a centralized threat management system, and incident response would follow a familiar sort of enterprise process. Furthermore, to ensure security policy compliance, one would expect the usual programs of end-user awareness, security training, and third-party audit to be directed toward the people building and operating national infrastructure. Virtually every national infrastructure protection initiative proposed to date has followed this seemingly straightforward path.3

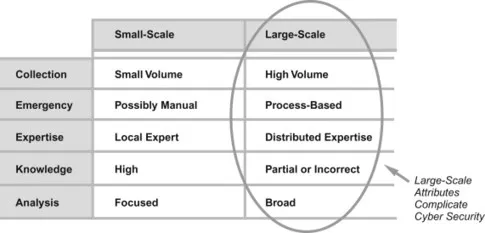

While well-known computer security techniques will certainly be useful for national infrastructure, most practical experience to date suggests that this conventional approach will not be sufficient. A primary reason is the size, scale, and scope inherent in complex national infrastructure. For example, where an enterprise might involve manageably sized assets, national infrastructure will require unusually powerful computing support with the ability to handle enormous volumes of data. Such volumes will easily exceed the storage and processing capacity of typical enterprise security tools such as a commercial threat management system. Unfortunately, this incompatibility conflicts with current initiatives in government and industry to reduce costs through the use of common commercial off-the-shelf products.

National infrastructure databases far exceed the size of even the largest commercial databases.

In addition, whereas enterprise systems can rely on manual intervention by a local expert during a security disaster, large-scale national infrastructure generally requires a carefully orchestrated response by teams of security experts using predetermined processes. These teams of experts will often work in different groups, organizations, or even countries. In the worst cases, they will cooperate only if forced by government, often sharing just the minimum amount of information to avoid legal consequences. An additional problem is that the complexity associated with national infrastructure leads to the bizarre situation where response teams often have partial or incorrect understanding about how the underlying systems work. For these reasons, seemingly convenient attempts to apply existing small-scale security processes to large-scale infrastructure attacks will ultimately fail (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Differences between small- and large-scale cyber security.

As a result, a brand-new type of national infrastructure protection methodology is required—one that combines the best elements of existing computer and network security techniques with the unique and difficult challenges associated with complex, large-scale national services. This book offers just such a protection methodology for national infrastructure. It is based on a quarter century of practical experience designing, building, and operating cyber security systems for government, commercial, and consumer infrastructure. It is represented as a series of protection principles that can be applied to new or existing systems. Because of the unique needs of national infrastructure, especially its massive size, scale, and scope, some aspects of the methodology will be unfamiliar to the computer security community. In fact, certain elements of the approach, such as our favorable view of “security through obscurity,” might appear in direct conflict with conventional views of how computers and networks should be protected.

National Cyber Threats, Vulnerabilities, and Attacks

Conventional computer security is based on the oft-repeated taxonomy of security threats which includes confidentiality, integrity, availability, and theft. In the broadest sense, all four diverse threat types will have applicability in national infrastructure. For example, protections are required equally to deal with sensitive information leaks (confidentiality), worms affecting the operation of some critical application (integrity), botnets knocking out an important system (availability), or citizens having their identities compromised (theft). Certainly, the availability threat to national services must be viewed as particularly important, given the nature of the threat and its relation to national assets. One should thus expect particular attention to availability threats to national infrastructure. Nevertheless, it makes sense to acknowledge that all four types of security threats in the conventional taxonomy of computer security must be addressed in any national infrastructure protection methodology.

Any of the most common security concerns—confidentiality, integrity, availability, and theft—threaten our national infrastructure.

Vulnerabilities are more difficult to associate with any taxonomy. Obviously, national infrastructure must address well-known problems such as improperly configured equipment, poorly designed local area networks, unpatched system software, exploitable bugs in application code, and locally disgruntled employees. The problem is that the most fundamental vulnerability in national infrastructure involves the staggering complexity inherent in the underlying systems. This complexity is so pervasive that many times security incidents uncover aspects of computing functionality that were previously unknown to anyone, including sometimes the system designers. Furthermore, in certain cases, the optimal security solution involves simplifying and cleaning up poorly conceived infrastructure. This is bad news, because most large organizations are inept at simplifying much of anything.

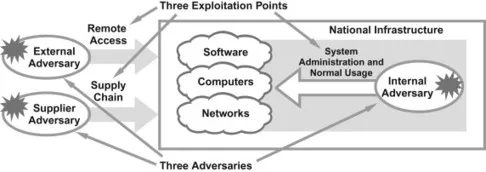

The best one can do for a comprehensive view of the vulnerabilities associated with national infrastructure is to address their relative exploitation points. This can be done with an abstract national infrastructure cyber security model that includes three types of malicious adversaries: external adversary (hackers on the Internet), internal adversary (trusted insiders), and supplier adversary (vendors and partners). Using this model, three exploitation points emerge for national infrastructure: remote access (Internet and telework), system administration and normal usage (management and use of software, computers, and networks), and supply chain (procurement and outsourcing) (see Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 Adversaries and exploitation points in national infrastructure.

These three exploitation points and three types of adversaries can be associated with a variety of possible motivations for initiating either a full or test attack on national infrastructure.

Five Possible Motivations for an Infrastructure Attack

- Country-sponsored warfare—National infrastructure attacks sponsored and funded by enemy countries must be considered the most significant potential motivation, because the intensity of adversary capability and willingness to attack is potentially unlimited.

- Terrorist attack—The terrorist motivation is also significant, especially because groups driven by terror can easily obtain sufficient capability and funding to perform significant attacks on infrastructure.

- Commercially motivated attack—When one company chooses to utilize cyber attacks to gain a commercial advantage, it becomes a national infrastructure incident if the target company is a purveyor of some national asset.

- Financially driven criminal attack—Identify theft is the most common example of a financially driven attack by criminal g...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgment

- 1: Introduction

- 2: Deception

- 3: Separation

- 4: Diversity

- 5: Commonality

- 6: Depth

- 7: Discretion

- 8: Collection

- 9: Correlation

- 10: Awareness

- 11: Response

- Appendix: Sample National Infrastructure Protection Requirements

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Cyber Attacks by Edward Amoroso in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Computer Science & Cyber Security. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.