eBook - ePub

Geoethics

Ethical Challenges and Case Studies in Earth Sciences

- 450 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Edited by two experts in the area, Geoethics: Ethical Challenges and Case Studies in Earth Sciences addresses a range of topics surrounding the concept of ethics in geoscience, making it an important reference for any Earth scientist with a growing concern for sustainable development and social responsibility.

This book will provide the reader with some obvious and some hidden information you need for understanding where experts have not served the public, what more could have been done to reach and serve the public and the ethical issues surrounding the Earth Sciences, from a global perspective.

- Written by a global group of contributors with backgrounds ranging from philosopher to geo-practitioner, providing a balance of voices

- Includes case studies, showing where experts have gone wrong and where key organizations have ignored facts, wanting assessments favorable to their agendas

- Provides a much needed basis for discussion to guide scientists to consider their responsibilities and to improve communication with the public

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Geoethics by Max Wyss,Silvia Peppoloni in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geology & Earth Sciences. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Section III

The Ethics Of Practice

Chapter 10

When Scientific Evidence is not Welcome…

Paul G. Richards Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University1, Palisades, NY, USA

Abstract

This chapter concerns interactions in the 1980s between the technical community and the Reagan administration. Reports to the US Congress from the executive branch of government had stated that the Soviet Union was “in likely violation” of the bilateral Threshold Test Ban Treaty (TTBT), which had been negotiated between the USA and the USSR in 1974 and which imposed a limit of 150 kilotons for the explosive yield of any underground nuclear weapons test conducted by these two countries after March 1976.

The TTBT had led to the need for making estimates of explosive yield, and several methods came into use of which the most prominent was based on seismology. In the specialized work of estimating explosive yield from analysis of the strength of seismic signals, the expert community became convinced that it was inappropriate to claim that the Soviets were cheating on this arms control treaty.

In a revealing TV interview, Assistant Secretary of Defense Richard Perle stated with reference to the opinion of seismologists on the size of the largest Soviet tests, “It’s not a question of scientific evidence. It’s a question of scientists playing politics.”

This chapter discusses Mr Perle’s claim here, from a personal perspective: why I became involved; briefly, what was the scientific evidence; and, most importantly, to what degree was it true that scientists were playing politics? Mr. Perle stated, “I didn’t much care what their answer was. It doesn’t have any profound bearing on our policy.”

To maintain a good professional reputation in the face of allegations of being biased because of a policy issue, an expert must be diligent to establish key facts and to defend them as bulwarks that may influence policy, with the potential to discredit policy makers who mischaracterize them. Seismological methods for measuring the size of the largest Soviet tests were endorsed by the results of two special nuclear explosions conducted in 1988 for which intrusive methods of monitoring were allowed.

The TTBT was eventually ratified in 1990 (by President G.H.W. Bush). Seismology continues to play a role in policy debates with reference to the much more important Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty of 1996.

Keywords

Underground nuclear explosions; Yield estimation; Nuclear arms control; Seismic monitoringPolicy issues that have a strong technical component, rooted in the geosciences, include responses to the prospect of climate change, national security decisions on dual use technologies,2 and options for nuclear arms control where there is an underlying need for consensus on technical aspects of monitoring capability. This chapter describes the treatment of a specific arms control policy issue that arose in the Reagan Administration (1981–1989). The technical component was very simple. It boiled down to an understanding of the relationship between the energy released by an underground nuclear explosion (UNE) and the P-wave magnitude of the seismic signals generated by the explosion. And because of the forcefully expressed opinions of a person speaking for the Administration, we are able to see in this case, very clearly, an unwelcome reaction to a conclusion that was strongly held by the technical community, and also some of the consequences of how this particular technical issue played out in the policy arena.

In the 1980s, the US Congress required annual reports from the executive branch of government on the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics’ compliance with arms control agreements. Some of these reports stated that the Soviet Union was “in likely violation” of the bilateral Threshold Test Ban Treaty (TTBT), which had been negotiated between the United States and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in 1974 and which imposed a limit of 150 kilotons (kt)3 on the explosive yield of any underground4 nuclear test explosion conducted by these two countries after March 1976.

Many methods of estimating nuclear explosive yield have been developed using remote observations—going back to the very first nuclear test explosion, of July 1945 (Trinity), in the atmosphere. Nuclear testing moved underground in later years and estimates of explosive yield began to be made using seismological methods. And then with the TTBT it became necessary to interpret yield estimates in the political context of assessing compliance with a formal arms control treaty.

The basic seismological observations were not seriously in dispute and were as follows: The largest underground explosions conducted by the United States at the Nevada Test Site (NTS), at yields that were reported by US agencies to be somewhat less than the 150 kt threshold, had seismic magnitudes of about 5.6–5.7. The Soviet Union after March 1976 conducted its largest underground tests mostly at the Semipalatinsk Test Site in Kazakhstan, at magnitudes that steadily attained higher and higher values over a few years, and that by the early 1980s were up at around magnitude 6.1.5 Since magnitude scales are logarithmic on a base of 10, this difference meant that the amplitude of signals recorded from the largest Soviet underground explosions were about 100.4 or 100.5 larger than the signals recorded from NTS. Since this factor is approximately 2.5–3, an assumption that the magnitude–yield relationship was the same for the Nevada and Semipalatinsk test sites led straightforwardly to estimates of the yield for the largest Soviet tests that were roughly three times greater than the largest tests in Nevada.6

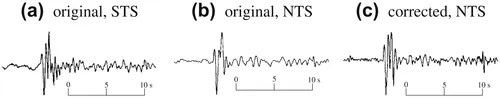

But from the early 1970s to the mid-1980s, a growing body of evidence emerged from seismology that the magnitude–yield relationship was not the same for the two test sites. For example, there was the observation that for stations on shield regions, at distances of several thousands of kilometers from Nevada or Kazakhstan, the signals from Soviet explosions had significantly higher frequency content than those from US explosions. This feature is described in Figure 1, which shows three seismograms. The first signal, at a station in Eskdalemuir, Scotland, with code name EKA, is from an underground nuclear explosion on June 30, 1971, of magnitude 5.9, at the Semipalatinsk Test Site. The second signal, also recorded at EKA, is from an underground nuclear explosion in granite on June 2, 1966, of magnitude 5.6, at the Nevada Test Site. Although the two test sites are at comparable distances from the recording station in Scotland, these seismograms are significantly different. The first, with its signal from Kazakhstan, contains higher frequencies than the second, with its signal from Nevada. From this and a broad range of other evidence, it is concluded that beneath the test site from which the higher frequencies are not observed, there must lie an attenuating region.

Furthermore, we can quantify the amount of this attenuation by modeling the way in which the original seismograms differ across the whole spectrum of frequencies. When the high-frequency components are restored to make the attenuated signal (from Nevada) match the unattenuated one, the outcome is as shown in the third seismogram of Figure 1.

The amount of the correction needed to make the seismograms (a) and (c) in Figure 1 look similar turns out to have an effect on the amplitude of the signal in the band of frequencies where the magnitude is measured. In this case, it was found that the effect of attenuation beneath the Nevada Test Site had reduced the size of the signal (b) recorded at EKA by about 0.3 magnitude units.

Many studies of this type have been done, using sources and seismographic recording stations all over the world.8 Several other lines of argument9 have also pointed to the conclusion that Nevada signals were being attenuated more than was the case for signals from Semipalatinsk. When this extra attenuation was quantified, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, like the United States, appeared to be observing a yield limit, which was about 150 kt, in its underground nuclear testing program.

The first evidence for differences in attenuation began to emerge in the early 1970s.10 The general subject of how to estimate yield by seismological means was vigorously pursued for 15 years, culminating, as we shall see, in 1988. Within the US research community, which was well funded from the 1960s to the 1980s by Department of Defense agencies seeking to improve monitoring capability, there developed a widening acceptance of the conclusion that teleseismic signals from sources in the tectonically active western United States (including NTS) were attenuated more than was the case for sources in stable continental regions such as ...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Section I. Philosophical Reflections

- Section II. Geoscience Community

- Section III. The Ethics Of Practice

- Section IV. Communication with The Public, Officials and The Media

- Section V. Natural and Anthropogenic Hazards

- Section VI. Low Income and Indigenous Communities

- Index