eBook - ePub

Translational Research in Coronary Artery Disease

Pathophysiology to Treatment

- 244 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Translational Research in Coronary Artery Disease

Pathophysiology to Treatment

About this book

Translational Research in Coronary Artery Disease: Pathophysiology to Treatment covers the entire spectrum of basic science, genetics, drug treatment, and interventions for coronary artery disease. With an emphasis on vascular biology, this reference fully explains the fundamental aspects of coronary artery disease pathophysiology.

Included are important topics, including endothelial function, endothelial injury, and endothelial repair in various disease states, vascular smooth muscle function and its interaction with the endothelium, and the interrelationship between inflammatory biology and vascular function.

By providing this synthesis of current research literature, this reference allows the cardiovascular scientist and practitioner to access everything they need from one source.

- Provides a concise summary of recent developments in coronary and vascular research, including previously unpublished data

- Summarizes in-depth discussions of the pathobiology and novel treatment strategies for coronary artery disease

- Provides access to an accompanying website that contains photos and videos of noninvasive diagnostic modalities for evaluation of coronary artery disease

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Translational Research in Coronary Artery Disease by Wilbert S. Aronow,John Arthur McClung,John Arthur Mcclung in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sciences biologiques & Génétique et génomique. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Endothelial Biology

The Role of Circulating Endothelial Cells and Endothelial Progenitor Cells

John Arthur McClung1 and Nader G. Abraham2, 1Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, New York Medical College, Valhalla, NY, USA, 2Department of Pharmacology, New York Medical College, Valhalla, NY, USA

Abstract

From the first description of circulating endothelial progenitor cells by Asahara and colleagues in 1997, our understanding of how the vascular endothelium tolerates stress and maintains its integrity has changed considerably. Endothelial biology in the adult constitutes a complex process of senescence, injury, and repair that is mediated by a complicated interaction of endothelial progenitor cells, sloughed circulating endothelial cells, microparticles, and an array of signaling proteins. This chapter will attempt to summarize what is currently known about this process, speculate on what new findings may lie ahead, and discuss the current state of our knowledge about manipulation of endothelial biology for the therapy of coronary artery disease. In so doing, it will elaborate our current understanding of endothelial cell turnover, the various factors that modify it, and the opportunities for both further research on and the clinical application of cell-based therapies.

Keywords

Endothelial biology; endothelial progenitor cells; circulating endothelial cells; microparticles; OEC; endothelial cell signaling; paracrine effects; vascular cell therapy

In Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, the king responds to the query of the White Rabbit as to where to begin by saying, “Begin at the beginning… and go on till you come to the end: then stop.” When dealing with cell turnover, the definition of the beginning is an open question, as a result of which, simply for purposes of discussion, this review will begin with the endothelial progenitor cell and go on from there.

What Are Endothelial Progenitor Cells?

Since Asahara et al. first isolated and described a population of what were termed “endothelial progenitor cells” (EPCs) in the peripheral blood at the end of the last century [1,2], a wealth of research has been generated that has further characterized these cells and in so doing raised more questions about both their identity and their behavior. Asahara’s original work identified a population of cells that were CD34 positive as well as vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR-2) positive that were capable of differentiating into endothelial cells in vitro, migrating in vivo to sites of vascular injury, and that enhanced the formation of new endothelium when infused into an organism. Given that both CD34 and VEGFR-2 are also expressed on mature endothelial cells, Peichev et al. demonstrated a population of circulating cells that also expressed CD133 in contradistinction to presumably mature human umbilical vein cells (HUVECs) which were CD133 negative [3].

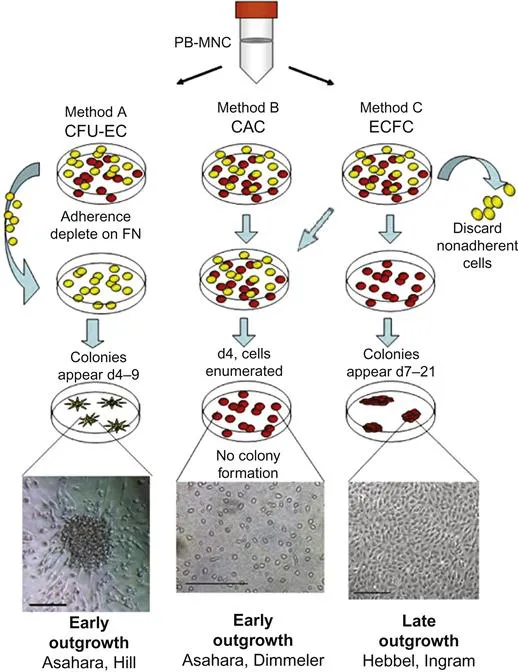

Concurrently, Gehling et al. isolated CD133+ cells from peripheral blood that, when plated on fibronectin for 14 days, were able to generate colony-forming units (CFUs) of apparently both hematopoietic and endothelial lineage cells [4]. Shortly thereafter, Hill et al. described a similar, but not identical, assay in which circulating mononuclear cells were cultured for 2 days with the nonadherent cells and were subsequently plated on fibronectin. Colonies were counted 7 days later and demonstrated an endothelial phenotype by histochemical staining for von Willebrand factor, VEGFR-2, and CD31 [5]. The number of colonies generated correlated negatively with the Framingham risk score and positively with the flow-mediated brachial index. Other investigators, using a similar technology, demonstrated that these cells could be incorporated into the damaged endothelium of a ligated left anterior descending coronary artery in a rat model [6]. A commercial assay using this technology was subsequently devised that used a 5-day protocol and has subsequently become known as the CFU-Hill Colony Assay.

In contradistinction to the CFU assay, Lin et al. plated human monocytes from which the nonadherent cells were removed at 24 h [7]. The remaining adherent cells were cultured and observed to have expanded significantly in bone marrow (BM) transplant recipients over the course of a month. Similarly, Vasa et al. evaluated the migratory capability of monocytes cultured for 2 days on fibronectin in which the adherent cells were isolated rather than the nonadherent cells [8]. These cells demonstrated significant migratory potential that appeared to be inversely proportional to the number of risk factors in a population of patients with coronary artery disease (CAD).

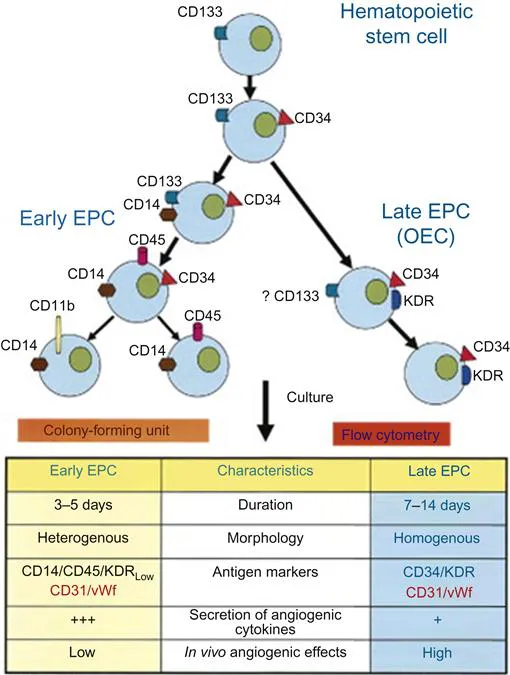

Hur et al. plated monocytes on endothelial basal medium and noted the appearance of spindle shaped cells similar to the original Asahara reports that increased in number for 14 days, after which replication ceased and the cells gradually disappeared by 28 days [9]. Another population of cells appeared after 2–4 weeks of incubation that rapidly replicated and demonstrated no evidence of senescence. These “late” EPCs, in contradistinction to “early” EPCs, were observed to successfully form capillaries when plated on Matrigel and were more completely incorporated into HUVEC monolayers. Notwithstanding, both early and late EPCs were equally effective at improving perfusion to an ischemic limb in a mouse model. Combining these two populations of cells was even more effective at enhancing ischemic limb perfusion [10].

Late EPCs have also been described as “outgrowth endothelial cells” (OECs) or “endothelial colony-forming cells” (ECFCs) by other investigators [7,11]. Using the approach of Lin and Vasa in which nonadherent cells were discarded and adherent cells were retained, investigators were able to culture a subpopulation of cells that appeared to be identical to Hur’s late EPCs, both morphologically and in their migratory behavior. Late EPCs appear to be distinctly superior to other EPC subpopulations in promoting angiogenesis, both in vitro and in vivo [12]. In addition to having a much higher rate of proliferation and resistance to apoptosis, this subpopulation has also been noted to have increased telomerase activity [11].

Sieveking et al. generated both early and late EPCs out of a single population of mononuclear cells that were plated on fibronectin with the nonadherent cells removed after 24 h [13]. Both early and late EPCs were observed to be CD34, CD31, CD146, and VEGFR-2 positive, however, only early EPCs expressed CD14 and CD45. Late EPCs formed branched interconnecting vascular networks, while early EPCs were observed to exhibit a marked augmentation of angiogenesis by a paracrine mechanism. These results are summarized in Figure 1.1 [14].

Thus, there appear to be at least four different methodologies for isolating putative EPCs from monocytes plated on fibronectin. The CFU assay cultures cells that are not adherent to the medium which form colonies at 4–9 days that are consistent with an early EPC phenotype. Hur et al. were able to grow both early and late EPCs from monocytes that were not separated out by their ability to either adhere or not to adhere to the medium. Sieveking et al. were able to grow both early and late EPCs from only adherent monocytes. Hence, it appears that nonadherent cells can generate only early EPC colonies, while adherent cells have the capability of generating both early EPC and OEC (Figure 1.2).

In addition to BM-derived cells, a recent study isolated a rare vascular endothelial stem cell in the blood vessel wall of the adult mouse that is CD117+ and c-kit+, and has the capacity to produce tens of millions of daughter cells that can generate functional blood vessels in vivo that connect to the host circulation [16]. The cellular regeneration of both the vascular and other components of a mouse digit tip in the context of CFU transplantation has been found to be composed of tissue-derived cells only [17].

All of these various cells have reparative capability when acting together, but precisely how this occurs is a matter of intense current research.

Paracrine Effects of BM-Derived Cells

CFU derived early EPCs secrete a number of agents, among them matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9, interleukin (IL)-8, macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF), angiopoeitin-1 (Ang-1), and thymidine phosphorylase (TP) in higher amounts than in early EPCs from adherent monocytes [18]. Early EPCs cultured from nonadherent monocytes secrete VEGF, stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1), insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) [19]. Early EPCs cultured from adherent monocytes secrete VEGF, HGF, granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF), and granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) [20].

Both VEGF and SDF-1 promote migration and tissue invasion of progenitor cells to a site of injury as well as enhance migration of mature endothelial cells [21–23]. IGF-1 promotes angiogenesis and inhibits apoptosis [24]. HGF markedly enhances angiogenesis [25]. G-CSF and GM-CSF enhance the migration of endothelial cells, and both have anti-inflammatory activity on vascular endothelium as well [26–28]. MMP-9 appears to be required for EPC mobilization, migration, and vasculogenesis, and IL-8 enhances both endothelial cell proliferation as well as survival [29,30]. Among other things, MIF appears to induce EPC mobilization [31]. Ang-1 is expressed from hematopoetic stem cells [32]. Along with VEGF, Ang-1 has been implicated in the recruitment of vasculogenic stem cells, and when BM mononuclear cells are enhanced by Ang-1 gene transfer, angiogenesis is improved both qualitatively and quantitatively [33,34]. TP has been demonstrated to both enhance endothelial cell migration and protect EPCs from apoptosis [18,35].

Early EPCs also have been shown to be repositories of both eNOS and iNOS which play a role in ischemic preconditioning and chronic myocardial ischemia, respectively [36,37]. More recently, prostacyclin (PGI2) has been identified as being secreted in very high levels by late (OEC) EPC [38].

Mechanisms, Known and Unknown

Mobil...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- List of Contributors

- Preface

- Biographies

- Chapter 1. Endothelial Biology: The Role of Circulating Endothelial Cells and Endothelial Progenitor Cells

- Chapter 2. The Role of Vascular Smooth Muscle Phenotype in Coronary Artery Disease

- Chapter 3. Immuno-Inflammatory Basis of Atherosclerotic Coronary Artery Disease

- Chapter 4. Adiponectin: A Mediator of Obesity, Insulin Resistance, Diabetes, and the Metabolic Syndrome

- Chapter 5. Use of Stem Cells in Ischemic Heart Disease

- Chapter 6. Vasculogenesis and Angiogenesis

- Chapter 7. Lipids in Coronary Heart Disease: From Epidemiology to Therapeutics

- Chapter 8. Genetics of Coronary Disease

- Chapter 9. The Role of Nitric Oxide and the Regulation of Cardiac Metabolism

- Chapter 10. Revascularization for Silent Myocardial Ischemia

- Chapter 11. Noninvasive Diagnostic Modalities for the Evaluation of Coronary Artery Disease

- Chapter 12. Current Approaches to Treatment of Ventricular Arrhythmias in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease

- Chapter 13. Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Clinical Use and Research Investigation in Coronary Artery Disease

- Chapter 14. Invasive Diagnostic Assessment of Coronary Artery Disease

- Chapter 15. Drug Treatment of Stable Coronary Artery Disease

- Chapter 16. Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

- Chapter 17. Current Topics in Bypass Surgery

- Chapter 18. Peripheral Veno-arterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Treatment of Ischemic Shock

- Chapter 19. Biostatistics Used for Clinical Investigation of Coronary Artery Disease

- Index