More complete understanding of the range of cultural influences on disease patterning will come as more frequent and profound interactions take place between the disciplines of medical anthropology and epidemiology, among others.

Rationale

In a context of growing populations, aging populations, and the rise of diseases of affluence, governments are increasingly concerned that future health care expenditures will be unsustainable. Thus, it is not surprising that disease prevention is high on national agendas. Making the job more difficult is the inevitability that disease control will always be a moving target. Infectious and chronic diseases emerge with changing ecologies, and the latter is an outcome to some extent of interactions between ever-evolving human genes and ever-changing environments. In this dynamic scenario public health leaders are questioning both the adequacy of population health research and the relevance of much of that research for developing effective interventions. As one of the pioneers of social epidemiology, Leonard Syme (2005, p. xi), said:

[In the last twenty years], we epidemiologists have suffered a whole series of embarrassing failures. … Our model is to identify the risk factors and share that information with a waiting public so that they will then rush home and, in the interests of good health, change their behaviours to lower their risk. It is a reasonable model, but it hasn’t worked. In intervention study after intervention study, people have been informed about the things they need to do, and they have failed to follow our advice.

He noted that the exigencies of daily life often hijacked intentions to behave more healthily; and in order to rectify epidemiology’s neglect of the fact that people have priorities in life beyond pursuing good health, Syme called on anthropologists and epidemiologists to collaborate more closely. In a context of the sedimentation of health risks among certain populations—inevitably the least powerful in society—another leading epidemiologist, Nancy Krieger (2001), called on social epidemiology to broaden its focus beyond identifying who is sick, and expend energy on examining “who and what is responsible for population patterns of health, disease and well-being.” She shared Syme’s concern about the need to understand and act on the pressure points that generate health behaviors.

One such pressure point concerns the genesis of cultural factors: ranging from individual biological traits, social group practices and rules, to globally circulating ideas and discourses. Thus it is timely that renewed attention is being paid to the proposition that culture can be causal, contributory, or protective in relation to ill health (Helman, 2007; Trostle, 2007; Hruschka and Hadley, 2008; Hahn and Inhorn, 2009).

We say “renewed” because in the mid-1800s, Rudolf Virchow, doctor, statesman, and anthropologist, proclaimed disease to accompany cultural loss (Virchow, 1848/2006). He argued that epidemics are warning signs against which the progress of states can be judged. More than a century later, and with many of the infectious disease epidemics of Virchow’s time remaining unconquered, lifestyle diseases (obesity, diabetes, lung and diet-related cancers) have joined a lengthy list contributing to the global burden of disease. Disconcertingly, less economically and socially powerful groups are more likely to experience multiple behavioral and disease risk factors (Lynch et al., 1997)—smoking, alcohol and drug abuse, poor nutrition—demanding investments in understanding the determinants that underpin the risks. In the absence of resource redistribution, including cultural capacity, their risk of unequal and unjust health status is also likely to persist across generations (Mackenbach, 2012).

There is widespread agreement that the reasons for inferior health outcomes are complex, involving socioeconomic factors (income, education, occupation), area-based factors (quality of water, sanitation, shelter, transport, nutrition), sociopolitical factors (gender, race, ethnicity), and sociocultural factors (values, rules, beliefs, behaviors). Culture forms part of the multifactorial etiology of disease operating in concert with social, economic, and political factors.

The primary aim of this book is then to encourage more sophisticated research designs, based on the inclusion of culture, however framed, in a range of public health research and intervention approaches in order to better explain and address contextual influences over population health behaviors. We provide researchers with conceptual and measurement tools to gain a more thorough understanding of the way culture helps “to produce asymmetries in the abilities of individuals and social groups to define and realise their [health] needs” (Johnson, 1986/1987, p. 39). At the same time, we want to avoid the situation where cultural explanations can be misused to blame people for their action or inaction. This situation arises when outsiders consider cultural matters to reflect ignorance or irrationality, rather than trying to understand local rationalities in relation to health and sickness.

Health behavior choices are shaped by belief and action systems, which arise in two ways. In part, they are based on local and historical understandings of disease, as well as the health systems available (e.g., Chinese complementary medicine, Ayurveda). They also result from interactions with environmental, economic, and political conditions, including government policies. Often overlooked are ways in which health policies can provide people with social status and material rewards for adopting certain behaviors (Farmer, 1999). For example, women who are the major food provisioners in many societies are enticed into labor markets through child-care subsidies and lowered benefits for stay-at-home women. While we might personally approve such initiatives, it must be recognized that the government’s actions are not simply economic in nature but also have significant repercussions for many facets of cultural life, whether they involve food, parenting, or gender relationships.

So what are we talking about when we refer to culture? Chapter 2 describes in greater detail how contested the term is within the field of anthropology, and other contributors to this book refer to their own struggles with the term.

Drawing from anthropology and sociology, we understand culture as operating like a blueprint guiding but not dictating what is imaginable, moral, and possible. Ideas, knowledge, language, discourses, and practices constitute a significant part of social activity. This array of different forms of culture does not arise from the ether but is promulgated by a variety of societal institutions, including religious and research bodies; government departments; the legal system; the system of production, exchange, and consumption; the kin, gender, and ethnic systems of authority; and the “world of commerce.” Individuals and communities also generate culture through initiating and practicing dialects, folk wisdom, and customary approaches to decision making, among other things. The resulting institutions, ideas, and practices that are generated change over time and are variable in their reach and effect depending on a people’s historical experience of new ideas as well as existing belief and local power systems. In short, culture is an ever-evolving guidance system, where the major actors may be in dispute about the legitimacy of what is being said and done.

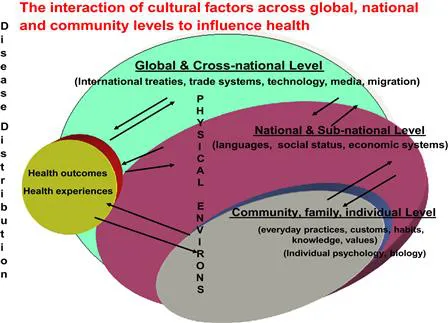

Second, we understand culture as described above (sets of meaning-laden behaviors, beliefs, artifacts) to produce “cultures,” or groups of people who carry a common culture. Cultures are found at multiple levels: global, nation state, village/community, social, group, family, and individual levels. At the global level, there are adherents to the global rule of law, trade rules, financial system rules, and environmental treaties along with ideas shared through migration, technology, and the media. At the national level, governments enact societal level laws and policies that are intended to encourage particular behaviors and not others. At the same time, a nation’s citizenry inherits and adapts practices from their forebears while reproducing and incrementally altering their culture through embracing new ideas, practices, and technologies.

At the level of the social group, cultural systems may legitimize/encourage or rule out/constrain decisions about how, when, where, and what health-related actions to take and equally what happens at this level can also change the cultural system. Forty years ago, for example, violence against women was tolerated in many nations. Then the second wave of the women’s movement emerged to demand that the perpetrators of violence become subject to legal and community sanctions. Nevertheless, long-standing cultural norms and values leave women subjected to subtler forms of symbolic violence, such as the portrayal of women in pornography.

At the level of the individual, there is growing interest in the idea of human adaptability, or the ability of populations to adjust biologically, culturally, and behaviorally to environmental conditions. Biocultural anthropology of health and disease acknowledges different cultural models of disease, and although these are influenced by environmental conditions they operate independently as Chapters 16 and 19 in this book make clear. This strand of research has been particularly vibrant in small-scale and sometimes premodern societies that are deeply embedded in, and reliant upon, their physical environment (Maddocks, 1978).

Culture’s importance as a determinant of individual health lies in the way that ideas, discourses, and ways of acting become embodied—a part of the taken-for-granted habitus or “the right way of doing things.” Until there is a big jolt—an epidemic, or change in life circumstances like marriage breakdown—socialized routines dominate reflexive (self-conscious) approaches. The extent of routinized and novel behaviors typically varies depending on the socioeconomic circumstances of people. Traditional or relatively rigid thoughts and actions may persist among often less powerful groups, those less exposed to novelty, and those who are under threat from ecological collapse or resource scarcity (Gelfand et al., 2011), but this may not be a bad thing because some traditions can protect against health risks (many traditional diets are preferable to the industrial diets implicated in so many chronic diseases). However, the adoption of new ideas and practices can also be health protective, and it is important to identify under what conditions traditional and new behaviors are beneficial.

As important as it is to identify relevant cultural “risk factors” (ideas, knowledge, or traditions) (operating at each level), it is also important to identify the sociocultural processes that facilitate the transmission of the ideas, discourses, practices, and other material effects of people acting together. So our third understanding of culture is as a process, consisting of a variety of mechanisms to transmit cultural factors, which exposes some in the population and not others. Anthropologists and sociologists have identified key processes of social transmission, including emulation, mimesis, magic, socialization, diffusion of innovations, social network effects, and social status distinction (Rogers, 1962; Bourdieu, 1984; Taussig, 1993; Gerbauer and Wulf, 1995; Bell, 1999; Borch, 2005). Global cultures are becoming more common, enabled by global media, mass migrations, and technologies, which facilitate flows of ideas, norms, and practices from one society to another (Appadurai, 1996).

A primary task for culture-in-health researchers is to identify the pathways by which ideas and practices arise, circulate, and are adopted, transformed, and repudiated.

For example, the logic of infectious disease contagion is now being applied to the spread of chronic disease. In studies of lung cancer, obesity, illicit drug use, and alcohol-related illness there is growing acceptance that health-compromising ideas, emotions, and consumption practices are highly contagious and constitute relevant risk factors (Ferrence, 2001; Pampel, 2005; Christakis and Fowler, 2007; Cockerham, 2007).

With our three-part understanding of culture, we echo Susser’s (2004) call for the development of an “eco-epidemiology,” which considers multiple levels of causation and risks and exposures across time and space. Figure 1 summarizes our understanding of culture as shared systems of ideas, rules, language, and practices generated and transmitted within and across various levels of social organization, interacting with physical environments and biological status, and along the way influencing health experiences and outcomes.

FIGURE 1.1 The levels at which culture impacts health.

A second aim of this book is to provide greater insight into how public health might more effectively influence culture to diffuse or spread healthy lifestyles. Against a backdrop of polic...