In Vivo Spectroscopy

Atomic nuclei with a magnetic moment (or “spin”) can exhibit resonance behavior in a magnetic field. This magnetic resonance effect is governed by the Larmor equation as a simple linear relationship between the magnetic field B perceived by the nucleus and the resultant resonance frequency ω.

The relative scaling γ, the so-called gyromagnetic ratio, is a nucleus-specific constant. The hydrogen nucleus 1H (i.e., a proton) is the prime example for an MR-sensitive isotope as 1H resonance signals from hydrogen nuclei bound in tissue water provide the basis for MR imaging (MRI) of the human body. Nuclear spins can be thought of as microscopic magnets. When placed in a magnetic field these magnetic moments become polarized, and are either parallel or antiparallel to the field. The spins that are polarized parallel to the field are in a lower energy state, so slightly more are present in this alignment than antiparallel to the field. When radiofrequency (RF) energy is applied to spins in a magnet at the Larmor frequency, the spins will absorb energy and undergo a transition from the antiparallel to the parallel state as with optical and other forms of resonance spectroscopy. MRS, however, differs in that in the process of absorption the spins will become polarized with the RF field such that when the RF field is shut off the spins will effectively rotate along the axis of the magnet (by convention the z-axis in MRS). This phenomenon creates a rotating magnetic field at the Larmor frequency. When an RF receiver coil is used the rotating magnetization induces an oscillating voltage by induction, which is then detected by the MR spectrometer (which is essentially a large RF transmitter and receiver). At field strengths available for clinical MRS the Larmor frequency will vary from ~60 to 300 MHz corresponding to magnet field strengths of 1.5 and 7.0 T, respectively. The low resonance frequency (6 to 7 orders of magnitude lower than optical resonances) is disadvantageous from a sensitivity standpoint, because the energy per absorption or emission is proportional to frequency. However, unlike optical spectroscopy or imaging, the human body is relatively transparent to RF at the MHz range and therefore is completely accessible to measurement by MRS.

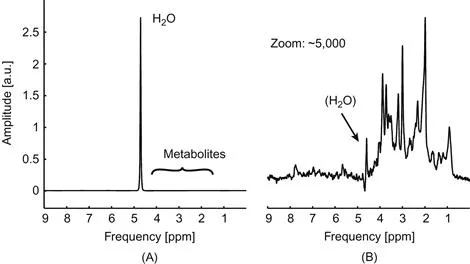

When a human subject is placed in the scanner of a given field strength, one could assume that all of the body’s 1H nuclei exhibit the same resonance frequency. In reality, however, minute frequency variations are observed depending on the molecular structure the atomic nucleus is embedded in. The field variations to cause these frequency shifts are based on two different effects. The electronic, i.e., the chemical, environment around the atomic nucleus at hand results in a so-called “chemical shift” and the correlation of different nuclei of the same molecule mediated through their binding electrons is referred to as dipolar or J-coupling. Chemical shift and J-coupling critically rely on the molecules’ chemical and geometric composition. As such, their measurement provides a wealth of intramolecular, microscopic information from a relatively simple, “macroscopic” MRS experiment. Notably, chemical shift and J-coupling are the basis for the key role MRS is playing in structural and analytical chemistry. Although chemical shift and J-coupling were discovered in the 1950s, it was not until 20 years later that MRS was applied to identify and quantify biochemicals in living cells (Shulman et al., 1979) and eventually in vivo (Ackerman et al., 1980). With this paradigm shift, the goal was no longer to study the physicochemical properties of substances, but to use the knowledge on the substance-specific spectroscopic patterns, i.e., their spectroscopic fingerprint, to separate and quantify these substances in vivo to infer the concentrations of metabolites and the fluxes of metabolic pathways.

MRS allows the noninvasive quantification of neurochemicals that contain MR-sensitive isotopes (e.g., 1H). Hydrogen is prevalent in most metabolites of the human brain and the 1H nucleus is the most relevant isotope for in vivo MRS. The gyromagnetic ratio of 1H is highest for all stable isotopes; therefore, its sensitivity in MR experiments is higher than for any other nucleus. Furthermore, the natural abundance of the 1H nucleus is almost 100%. The first in vivo MRS measurements of the living brain were in 1982 on a small-bore high-field MR system (Behar et al., 1983). With the subsequent rapid development of large-bore high-field magnets and volume localization by the mid-1980s, the first 1H MR spectra of human brain were obtained (Bottomley et al., 1983; Frahm et al., 1989) and today 1H MR spectra can be somewhat routinely obtained on all clinical MRI systems of 1.5 T and higher in field strength.

Although a series of brain metabolites can be identified with 1H MRS (Govindaraju et al., 2000), the number of substances that are assessable under in vivo conditions does not exceed 15–20 (Mekle et al., 2009; Tkac et al., 2009; Emir et al., 2011a) and is typically well below. Further MR-visible isotopes with biochemical relevance have been shown to provide valuable information on tissue physiology and biochemistry. Phosphorus (31P) MRS, for instance, allows the quantification of key components of the tissues’ energy metabolism (ATP, ADP, and phosphocreatine) and to study, for example, bioenergetic deficits in response to disease (Befroy & Shulman, 2011). MRS employing the 13C isotope enables the study of Krebs (TCA) cycle intermediates, and the predictable transfer of infused 13C-label between specific positions of the carbon chains of these intermediates stands out by providing turnover rates and metabolic fluxes (Rothman et al., 2011). Today’s clinical MRS, however, mostly relies on 1H whereas other nuclei are predominantly used in basic and preclinical research. The need for nonstandard hardware and specialized MRS methods for non-1H MRS might be reasons why these applications have yet to prevail in clinical practice. This chapter therefore focuses on the basic principles of 1H MRS, although where appropriate extensions to other nuclei will be discussed (for more detail on this topic see Chapters 4.1–4.3.).