![]()

1

Principles of knowledge management

Introduction

It is traditional to start a book of this type with the discussion of ‘what is knowledge’?, and ‘what is knowledge management’?. If you are already quite clear about the topic, then this chapter is not for you. However, there is often still some confusion over the definitions of, and fuzzy boundaries between, knowledge management, information management and data management. The two latter disciplines are well established; people know what they mean, people are trained in them, there are plenty of reference books that explain what they are and how they work. Knowledge management, on the other hand, is a relatively new term and one that requires a little bit of explanation. If you would rather jump on to the practical applications, start at Chapter 2 and come back to Chapter 1 another day.

The greater part of Chapter 1 necessarily covers much of the same ground as the corresponding sections in Milton (2004)1 and in Young (2009).2 If you own and have read these two books, you can move on to Chapter 2.

We will start by looking at ‘what is knowledge?’

What is knowledge?

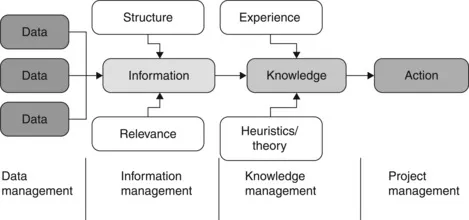

Knowledge (according to Peter Senge3) is ‘the ability to take effective action’ (the Singapore Armed Forces further refine this definition as ‘the capacity to take effective action in varied and uncertain situations’). Knowledge is something that only humans can possess. People know things and can act on them; computers can’t know things and can only respond. This ability to take effective action is based on experience and it involves the application of theory or heuristics (rules of thumb) to situations – either consciously or unconsciously. Knowledge has something that data and information lack, and those extra ingredients are the experience and the heuristics (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Data, information and knowledge

Knowledge is situational and what works in one situation may not work in another.

As an illustration, consider the link between data, information and knowledge as they are involved in decision-making in a marketing organisation:

The company pays for a market research survey, conducting interviews with a selection of consumers in several market segments. Each interview is a datapoint. These data are held in a database of survey responses.

In order for these data to be interpreted, they need to be presented in a meaningful way. The market research company analyses the data and pulls out trends and statistics that they present as charts, graphs and analyses.

However, you need to know what to do with this information. You need to know what action to take as a result. Such information, even presented in statistics and graphs, is meaningless to the layman, but an experienced marketer can look at it, consider the business context and the current situation, apply their experience, use some theory, heuristics or rules of thumb, and can make a decision about the future marketing approach. That decision may be to conduct some further sampling, to launch a new campaign, or to rerun an existing campaign.

The experienced marketer has ‘know-how’ – he or she knows how to interpret market research information. They can use that knowledge to take the information and decide on an effective action. Their knowhow is developed from training, from years of experience, through the acquisition of a set of heuristics and working models, and through many conference and bar-room conversations with the wider community of marketers.

Knowledge that leads to action is ‘know-how’. Your experience, and the theories and heuristics to which you have access, allow you to know what to do, and to know how to do it. In this book, you can use the terms ‘knowledge’ and ‘know-how’ interchangeably.

In large organisations, and in organisations where people work in teams and networks, knowledge and know-how are increasingly being seen as a communal possession, rather than an individual possession. In some companies it will be the communities of practice that have the collective ownership of the knowledge, while in others it will be the regional sales teams that have the collective ownership. Such knowledge is ‘common knowledge’ – the things that everybody knows. This common knowledge is based on shared experiences and on collective theory and heuristics that are defined, agreed and validated by the community.

Tacit and explicit knowledge

The terms tacit and explicit are often used when talking about knowledge. The original author, Polyani (1966),4 used these terms to define ‘unable to be expressed’ and ‘able to be expressed’ respectively. Thus, in the original usage, tacit knowledge means knowledge held instinctively, in the unconscious mind and in the muscle memory, which cannot be transferred into words. Knowledge of how to ride a bicycle, for example, is tacit knowledge, as it is almost impossible to explain verbally.

Following the seminal text by Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995)5 these original definitions have become blurred, and tacit and explicit are often used to describe ‘knowledge which has not been codified’ and ‘knowledge which has been codified’ (or ‘head knowledge’ and ‘recorded knowledge’ respectively). This latter definition is a more useful one in the context of knowledge management within organisations, as it defines knowledge based on where it exists, rather than on its intrinsic codifiability. So, knowledge that exists only in people’s heads is often termed tacit knowledge, and knowledge that has been recorded somewhere is termed explicit knowledge. Knowledge can therefore be transferred from tacit to explicit, according to Nonaka and Takeuchi.

There is a wide range of types of knowledge, from easily codifiable to completely uncodifiable. Some know-how, such as how to cook a pizza, can be codified and written down; indeed, most households contain codified cooking knowledge (cookery books). Other know-how, such as how to whistle or how to dance the tango, cannot be codified, and there would be no point in trying to teach someone to dance by giving them a book on the subject.

Sales and marketing knowledge comprises a wide range of codifiability. Some of it can never be fully written down, e.g. how to establish a lasting relationship with a client, and must be transferred through coaching and role-play, while some of it can be easily codified into company guidelines.

What is knowledge management?

If knowledge is a combination of experience, theory and heuristics, developed by an individual or a community of practice, that allows decisions to be made and correct actions to be taken, then what is knowledge management? Larry Prusak of McKinsey Consulting says, ‘It is the attempt to recognise what is essentially a human asset buried in the minds of individuals, and leverage it into a corporate asset that can be used by a broader set of individuals, on whose...