Bioactive Food as Dietary Interventions for Liver and Gastrointestinal Disease

Bioactive Foods in Chronic Disease States

- 802 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Bioactive Food as Dietary Interventions for Liver and Gastrointestinal Disease

Bioactive Foods in Chronic Disease States

About this book

Bioactive Food as Dietary Interventions for Liver and Gastrointestinal Disease provides valuable insights for those seeking nutritional treatment options for those suffering from liver and/or related gastrointestinal disease including Crohn's, allergies, and colitis among others. Information is presented on a variety of foods including herbs, fruits, soy and olive oil. This book serves as a valuable resource for researchers in nutrition, nephrology, and gastroenterology.- Addresses the most positive results from dietary interventions using bioactive foods to impact diseases of the liver and gastrointestinal system, including reduction of inflammation, improved function, and nutritional efficiency- Presents a wide range of liver and gastrointestinal diseases and provides important information for additional research- Associated information can be used to understand other diseases, which share common etiological pathways

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Chapter 1

The Alkaline Way in Digestive Health

1 Dietary Factors in Metabolism

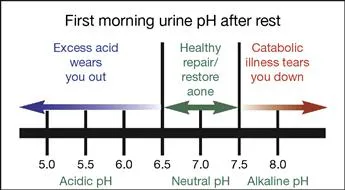

1.1 Profile: Metabolic Acidosis as a Major Cause of Chronic Disease

1.1.1 Associated signs and symptoms

1.1.1.1 Fatigue

1.1.1.2 Osteopenia and osteoporosis

1.1.2 Relevant evaluations

1.1.2.1 Self-evaluation: Testing for pH

1.1.2.2 Laboratory evaluation: Reducing immune reactivity

1.1.3 Clinical interventions: the alkaline way

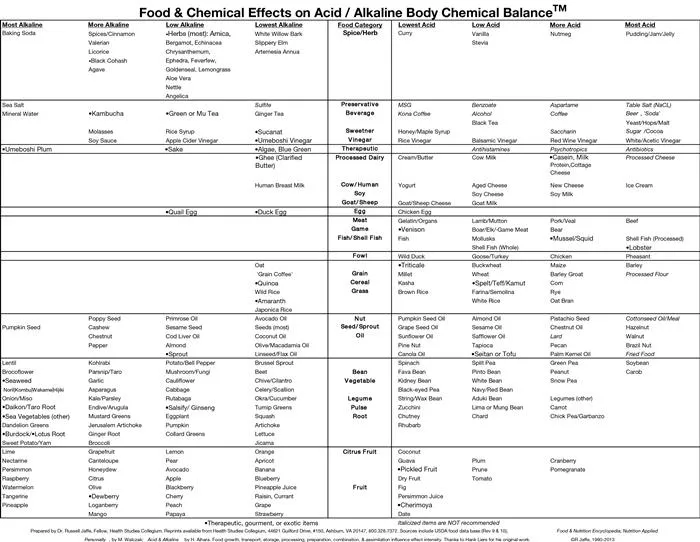

1.1.3.1 Alkaline diet

1.1.3.1.1 Enhancing immune defenses

1.1.3.1.2 Buffering cellular chemistry

1.1.3.2 Alkaline nutrients

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments for Bioactive Foods in Chronic Disease States

- Copyright

- Preface: Liver and Gastrointestinal Health

- Contributors

- Chapter 1. The Alkaline Way in Digestive Health

- Chapter 2. Functional Assessment of Gastrointestinal Health

- Chapter 3. Antioxidants in Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Ulcerative Colitis, and Crohn Disease

- Chapter 4. Omega-6 and Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Inflammatory Bowel Diseases

- Chapter 5. Alcohol and Gastrointestinal Tract Function

- Chapter 6. Dangerous Herbal Weight-Loss Supplements

- Chapter 7. Milk Bacteria: Role in Treating Gastrointestinal Allergies

- Chapter 8. Nutritional Functions of Polysaccharides from Soy Sauce in the Gastrointestinal Tract

- Chapter 9. Nutrition, Dietary Fibers, and Cholelithiasis: Cholelithiasis and Lipid Lowering

- Chapter 10. Indian Medicinal Plants and Spices in the Prevention and Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis

- Chapter 11. Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe): An Ancient Remedy and Modern Drug in Gastrointestinal Disorders

- Chapter 12. The Role of Microbiota and Probiotics on the Gastrointestinal Health: Prevention of Pathogen Infections

- Chapter 13. Probiotics and Irritable Bowel Syndrome

- Chapter 14. Antioxidant, Luteolin Exhibits Anti-inflammatory Effect in In Vitro Gut Inflammation Model

- Chapter 15. Human Microbiome and Diseases: A Metagenomic Approach

- Chapter 16. Folate Production by Lactic Acid Bacteria

- Chapter 17. Probiotics against Digestive Tract Viral Infections

- Chapter 18. Probiotic Bacteria as Mucosal Immune System Adjuvants

- Chapter 19. Medicinal Plants as Remedies for Gastrointestinal Ailments and Diseases: A Review

- Chapter 20. Review on the Protective Effects of the Indigenous Indian Medicinal Plant, Bael (Aegle marmelos Correa), in Gastrointestinal Disorders

- Chapter 21. Gastrointestinal and Hepatoprotective Effects of Ocimum sanctum L. Syn (Holy Basil or Tulsi): Validation of the Ethnomedicinal Observation

- Chapter 22. Turmeric (Curcuma longa L.) the Golden Curry Spice as a Nontoxic Gastroprotective Agent: A Review

- Chapter 23. Nutrition, Dietary Fibers, and Cholelithiasis: Apple Pulp, Fibers, Clinical Trials

- Chapter 24. Gastrointestinal Protective Effects of Eugenia jambolana Lam. (Black Plum) and Its Phytochemicals

- Chapter 25. Preventing the Epidemic of Non-Communicable Diseases: An Overview

- Chapter 26. Omega 3 Fatty Acids and Bioactive Foods: From Biotechnology to Health Promotion

- Chapter 27. Carotenoids: Liver Diseases Prevention

- Chapter 28. Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Early Life Nutritional Programming: Lessons from the Avian Model

- Chapter 29. Prebiotics, Probiotics, and Health Promotion:: An Overview

- Chapter 30. Gastroprotective Effects of Bioactive Foods

- Chapter 31. Antioxidant Activity of Anthocyanins in Common Legume Grains

- Chapter 32. Antioxidant Capacity of Pomegranate Juice and Its Role in Biological Activities

- Chapter 33. Dietary Bioactive Functional Polyphenols in Chronic Lung Diseases

- Chapter 34. Antioxidant Capacity of Medicinal Plants

- Chapter 35. Chinese Herbal Products in the Prevention and Treatment of Liver Disease

- Chapter 36. Bioactive Foods and Supplements for Protection against Liver Diseases

- Chapter 37. The Role of Prebiotics in Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases

- Chapter 38. The Role of Curcumin in Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases

- Chapter 39. Toll-Like Receptors and Intestinal Immune Tolerance

- Chapter 40. Psychological Mechanisms of Dietary Change in Adulthood

- Chapter 41. Biochemical Mechanisms of Fatty Liver and Bioactive Foods: Fatty Liver, Diagnosis, Nutrition Therapy

- Chapter 42. Hepatoprotective Effects of Zingiber officinale Roscoe (Ginger): A Review

- Chapter 43. Betel Leaf (.0Piper betel Linn): The Wrongly Maligned Medicinal and Recreational Plant Possesses Potent Gastrointestinal and Hepatoprotective Effects

- Chapter 44. Hepatoprotective Effects of Picroliv: The Ethanolic Extract Fraction of the Endangered Indian Medicinal Plant Picrorhiza kurroa Royle ex. Benth

- Chapter 45. Scientific Validation of the Hepatoprotective Effects of the Indian Gooseberry (Emblica officinalis Gaertn): A Review

- Chapter 46. Biochemical Mechanisms of Fatty Liver and Bioactive Foods: Wild Foods, Bioactive Foods, Clinical Trials in Hepatoprotection

- Chapter 47. Phytochemicals Are Effective in the Prevention of Ethanol-Induced Hepatotoxicity: Preclinical Observations

- Index