I Introduction

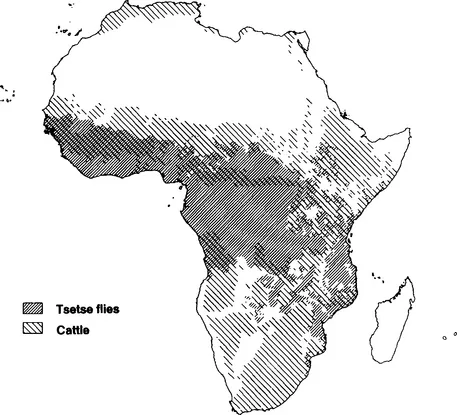

African trypanosomes are protozoan parasites that cause disease in humans and livestock. Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense and T. brucei gambiense both cause sleeping sickness in humans. Other species such as T. brucei brucei, T. congolense, T. vivax, and T. evansi are not infective to humans, but all cause disease in livestock. At present 50 million people are at risk of contracting human trypanosomiasis. In addition, trypanosomiasis in livestock causes severe economic problems. In Africa alone, the widespread distribution of the tsetse fly, which is the vector for most economically important trypanosome species, makes 10 million square kilometers of potential grazing land unsuitable for livestock breeding (Fig. 1). Furthermore, roughly one-third of the cattle heard in Africa is presently at risk from the disease. Annual losses in meat production alone are estimated at U.S. $5 billion, according to the annual report of the International Laboratory for Research on Animal Diseases (ILRAD, 1989). This economic deprivation is exacerbated by a loss of milk production and a loss of tractive power. In this context it is appropriate to mention that T. evansi infects camels in Africa and in the Middle East and domestic buffaloes in Asia.

Figure 1 Distribution of tsetse flies and cattle in Africa. About one-third of the continent is unsuitable for cattle breeding owing to the widespread distribution of the tsetse fly. The impact of trypanosomiasis is even greater than this figure suggests because the areas inhabited by tsetse flies are potentially the most agriculturally productive in Africa. (Map kindly provided by Dr. R. Kruska.)

Tsetse flies only occur in Africa and Saudi Arabia. However, some trypanosome species can be transmitted in the absence of tsetse flies and can be found far outside the African tsetse belt. Trypanosoma evansi only exists as bloodstream forms and is transmitted through mechanical transfer by biting flies. The parasites are found in Asia, South America, and tsetse-free regions of Northern Africa. Trypanosoma vivax is transmitted by tsetse flies in Africa but can be found in South and Central America, where it exists in the absence of this vector. Trypanosomiasis is considered to be the major disease constraint on livestock development in Africa (Morrison et al, 1981b), but its importance is clearly not restricted to the African continent.

Most trypanosomes do not manifest a strict host tropism and can infect a variety of livestock species. They also infect wild animals, which form a reservoir from which the tsetse flies continuously reinfect livestock. Infected animals develop fever, lose weight, and progressively become weak and unproductive. Left untreated, many animals die from anemia, heart failure, and opportunistic bacterial infections. In humans, a similar course of events takes place, with parasites spreading into the central nervous system to cause the syndrome of sleeping sickness.

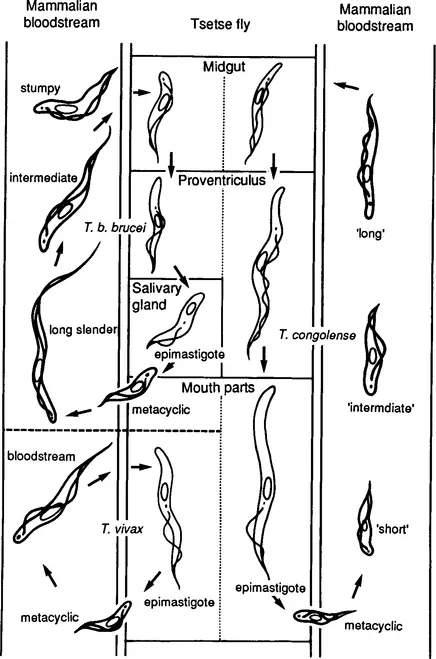

Figure 2 summarizes the life cycles for T. congolense, T. vivax, and T. b brucei, which is representative for the trypanosomes from the brucei group. The parasites live free in the blood and lymphoid tissues of the vertebrate host and are transmitted by tsetse flies. In all three species the parasites exist in the trypomastigote form in the vertebrate host. However, whereas T. b. brucei bloodstream forms are very pleiomorphic, this is not so for T. vivax or T. congolense. Following ingestion by tsetse flies feeding on an infected host, the bloodstream trypomastigotes transform to epimastigotes and later to metacyclic trypomastigotes. This transformation occurs in various locations depending on the trypanosome species (Fig. 2). In the vertebrate host, the parasites are covered by a surface coat that disappears in the tsetse fly and reappears on the metacyclic forms (Vickerman, 1978). The forms expressing a coat are shown in heavy outlines in Fig. 2. When the tsetse fly bites the vertebrate host, the metacyclic trypomastigotes are injected in the skin along with tsetse saliva, and a chancre develops at the site of bite. Chancre development, however, is not so marked in infections with T. vivax. The metacyclic trypomastigotes develop further in the chancre and transform into the bloodstream trypomastigotes, entering the local lymph vessels and later the bloodstream. The bloodstream forms may enter the connective tissues of the animal, although this is not usually observed with T. congolense. During human sleeping sickness, the parasites ultimately spread into the central nervous system.

Figure 2 Life cycles of T. b. brucei, T. vivax, T. congolense. The forms with a surface coat are shown in heavy outlines. [Reproduced with permission from the ILRAD Annual Report (1989).]

The morphological pleiomorphism of the bloodstream trypomastigotes seen during infection with T. b. brucei is associated with changes in metabolism. In the long slender forms, the mitochondrium is reduced to a peripheral canal, the Krebs cycle is not functional, and cytochromes are absent (Opperdoes, 1987). The parasites depend totally on glycolysis for their energy supply, and the NADH produced is reoxidized via a glycerol-3-phosphate oxidase system that is cyanide insensitive. In the short stumpy forms, which are nondividing differentiation forms (Shapiro et al., 1984), the mitochondrium is enlarged and fully active. This transformation is often considered as a preadaptation to the insect environment, where glucose is obviously not as abundant as in the blood of the mammalian host. The insect forms have an active mitochondrium. Glucose metabolism in bloodstream trypanosomes differs from glycolysis in other eukaryotes, and many of the enzymes involved in glycolysis are organized in specialized organelles named glycosomes (Opperdoes, 1987).

Trypanosomes from the brucei group are morphologically indistinguishable, and the different subspecies have been classified on the basis of geographical localization and host tropism. Trypanosoma brucei gambiense and T. b. rhodesiense both cause sleeping sickness in humans, whereas T. b. brucei is unable to infect humans and is lysed by human serum in vitro. The trypanolytic component of human serum has been identified as high-density lipoprotein (Rifkin, 1978). Since T. b. rhodesiense can be passaged through livestock species without losing infectivity for humans, sensitivity to lysis by human serum in vitro has been widely used as a more appropriate method for classification. However, some T. b. rhodesiense clones are able to switch from a serum-sensitive to a serum-resistant form and vice versa (Van Meirvenne et al., 1976) owing to the on–off switching of a single gene (De Greef et al., 1989). As a consequence, human noninfective forms of T. b. rhodesiense have regularly been classified as T. b. brucei. On the basis of isoenzyme patterns, it was found that T. b. gambiense is sufficiently different from the two other groups to be considered as a subspecies (Tait et al., 1984). However, T. b. brucei and T. b. rhodesiense are very closely related, and it is not clear whether they should be considered subspecies or variants of one species.