- 230 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Advances in Filament Yarn Spinning of Textiles and Polymers

About this book

Advances in Filament Yarn Spinning of Textiles and Polymers reviews the different types of spinning techniques for synthetic polymer-based fibers, and issues such as their effect on fiber properties, including melt, dry, wet, and gel spinning.

Synthetic polymer-based fibers are used in a great variety of consumer and industrial textile applications ranging from clothing to home furnishings to surgical procedures. This book explores how a wide array of spinning techniques can be applied in the textile industry. Part one considers the fundamental structure and properties of fibers that determine their behavior during spinning. The book then discusses developments in technologies for manufacturing synthetic polymer films to produce different fibers with specialized properties. Part two focuses on spinning techniques, including the benefits and limitations of melt spinning and the use of gel spinning to produce high-strength and high-elastic fibers. These chapters focus specifically on developments in bi-component, bi-constituent, and electro-spinning, in particular the fabrication of nanocomposite fibers. The final chapters review integrated composite spinning of yarns and the principles of wet and dry spinning.

This collection is an important reference for a wide range of industrial textile technologists, including spinners, fabric and garment manufacturers, and students of textile technology. It is also of great interest for polymer scientists.

- Reviews the different spinning techniques and issues such as their effect on fiber properties, including melt, dry, wet, and gel spinning

- Considers the fundamental structure and properties of fibers that determine their behavior during spinning

- Reviews integrated composite spinning of yarns and the principles of wet and dry spinning

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Advances in Filament Yarn Spinning of Textiles and Polymers by Dong Zhang in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Materials Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

General issues

Outline

1 Synthetic polymer fibers and their processing requirements

2 Understanding the behaviour of synthetic polymer fibres during spinning

3 Technologies for the manufacture of synthetic polymer fibers

1

Synthetic polymer fibers and their processing requirements

G. Bhat and V. Kandagor, The University of Tennessee, USA

Abstract:

In order to understand the structure and properties of the desired polymer products, we should have a comprehensive knowledge of the process optimization conditions and materials characteristics. The fundamentals that determine the structure and properties of polymeric fibers include the composition, the molecular structure of the polymer, and morphological features such as crystallinity and orientation. Understanding these factors will be the key to determining correctly the manufacturing process from polymerization to fiber spinning, drawing, and post treatment of manufactured fibers. The inherent qualities of existing natural fiber-forming materials, their limitations and applications, are also discussed.

Key words

polymerization; fiber spinnability; rheology; natural fibers; synthetic fibers; high performance fibers

1.1 Introduction

The history of man-made fibers dates back to the nineteenth century and has evolved to become one of the most widely-researched fields of technology. During the past 50 years, the need to understand the fundamental theory of fiber formation, combined with the demand for high quality fibers, has attracted the attention of many polymer scientists. For thousands of years, silk, cotton, and wool had been successfully used as textiles, but some drawbacks, for example the tendency of cotton to wrinkle, the delicate handling of silk, and the shrinking characteristics of wool, limited their application. But in 1903, rayon, the first manufactured fiber, was developed. Advances in the understanding of fiber chemistry across a wide spread of applications began to emerge. By 1950, over 50 different types of man-made polymeric fibers had been produced. This historic advance in fiber technology was preceded by the modification of naturally occurring polymers. An advancing and deepening understanding of the background chemistry and physics of polymers has enabled the manipulation of polymers, making possible end products driven by consumer needs.1

In order to understand the relationship between processing conditions and the characteristic properties of desired polymer products, a comprehensive knowledge of optimal conditions and material characteristics is necessary. This can be achieved only by understanding the fundamentals of polymers and polymer technology. The fundamentals determining the structure and properties of polymeric fibers include the composition, the molecular structure of the polymer, and morphological features such as crystallinity and orientation. An understanding of these factors is the key to determining the manufacturing process from synthesis of the monomer to polymerization, fiber spinning, and drawing through to the final product.

1.1.1 Types of fiber

Fibers are materials with a very high aspect ratio, or elongated continuous structures, similar to the lengths of thread and varying in diameter from millimeters to nanometers. Most of the commonly used fibers, whether natural or synthetic, tend to be polymeric in nature. Fiber-forming polymers can be categorized as synthetic and natural fibers, and commodity and specialty fibers. Polymers are macromolecular and in their simplest form consist of basic chemical structural units that are identical and linked together by well-defined bonds. The specific type of bond is particularly important in determining the molecular structure and architecture of the polymer. In polymer structure, the number of repeating units in a chain, or the molecular weight of the polymer, is very important in determining its characteristics and applications. The molecular weight of a fiber-forming polymer is not monodispersed, but is rather an average of the molecular weights of the chains that exist in a polymer sample. The molecular weight of the sample is an important property of the polymer, because it determines the tensile strength and influences the physical properties of the material.

Natural and synthetic fibers

Natural fibers originate in geological processes, plants, or animals, and are generally degradable, mainly as a function of time and the environmental conditions to which they are subjected. Synthetic fibers are made from materials that are chemically synthesized and may sometimes imitate natural products. Following World War II, global advances in technology enabled the fabrication of materials equal in strength, appearance, and other characteristics to natural materials. They were also lower in cost. Synthetic fibers can be made from polymers, metals, carbon, silicon carbide, fiberglass, and minerals. This book focuses mainly on polymeric fibers.

The majority of fiber-forming polymers, like common plastics, are based on petrochemical sources. Polymeric fibers can be produced from the following materials: polyamide nylon, polyethylene terephthalate (PET) or polybutylene terephthalate (PBT) polyesters, phenol-formaldehyde (PF), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), and polyolefins (polypropylene (PP) and polyethylene (PE)) among others. Because of the different chemical structures of fiber-forming polymers, their applications vary widely according to the temperature and chemical conditions which they can withstand. For example, polyethylene melts into a viscous liquid at temperatures equal to or less than that of a domestic dryer and therefore its application in a product that will require normal laundering is not possible. However, its fibers can be used in making disposable non-woven products.2

Commodity, specialty, and engineered fibers

Most nylons, polyesters and polypropylenes are commodity fibers and have the required properties for apparel and upholstery applications. Specialty polymer fibers are made from plastic materials and have unique characteristics, such as ultra-high strength, electrical conductivity, electro-fluorescence, high thermal stability, higher chemical resistance, and flame retardancy. PE, for instance, a polymer commonly used in the manufacture of disposable shopping bags and refuse bags, is a cheap, low friction coefficient polymer, and is considered a commodity plastic. Medium-density polyethylene (MDPE) is used for underground gas and water pipes; ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene (UHMWPE) is an engineering plastic used extensively for glide rails in industrial equipment and for the low friction sockets in implanted hip joints. It is also used to produce Spectra® or Dyneema®, the fiber having the highest specific strength.

Another industrial application of this material is the fabrication of composite materials consisting of two or more macroscopic phases. Steel-reinforced concrete is one example, and another is the plastic casing used for television sets and cell-phones. This plastic casing is usually of composite materials consisting of a thermoplastic matrix such as acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene (ABS) to which calcium carbonate chalk, talc, glass fibers, or carbon fibers have been added to enhance strength, bulk, or electro-static dispersion. These additions may be referred to as reinforcing fibers or dispersants, depending on their purpose.

It should be noted here that the dividing line between the various types of plastics is not based on the materials, but rather on their properties and applications.

1.2 Chemistry of fiber-forming polymers

To manufacture useful products from polymers, it is necessary to shape them. This can be achieved by changing the characteristics of a polymer from hard to soft. The two kinds of polymers mainly applied in manufacturing are thermoplastics and thermosets. Thermoplastics, which can easily be melted by subjecting them to the right combination of heat and pressure without necessarily changing the chemical structure, are the most widely used polymers for fiber products. Thermoplastics consist of individual polymer chains that are connected to each other physically rather than chemically. When heated, these chains slide past each other, causing the polymer to become rubbery, eventually causing a flow that enables easier processing. Examples include polyethylene for making milk containers and grocery bags, and polyvinyl chloride for making house wall sidings.

Thermosets consist of interconnected chains with a fixed position relative to each other. These polymers disintegrate into char when subjected to heat because they cannot flow. Examples of thermosets include epoxy resins, Bakelite, and vulcanized rubber, where the individual polymers are chemically interconnected. The chemical crosslinks prevent reorganization of the polymer when subjected to heat, and break only when the thermal energy exceeds the bonding energy between the crosslinks, thus causing disintegration and charring at higher temperatures.

1.2.1 Polymerization

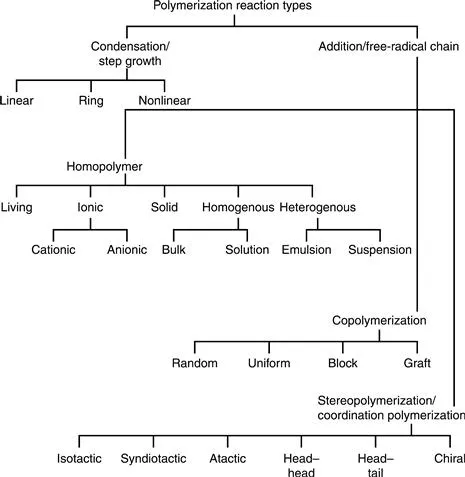

Polymerization is the process of converting a starting chemical, called the monomer, to a long chain molecule, the polymer, which is the basic structure of almost all fibers. The polymerization process will differ according to the chemical composition/structure of the starting monomer. Figure 1.1 below shows the different kinds of polymerization reactions.3–5 It is obvious that there are many choices, and selection of the polymerization process depends on several factors. Some of these aspects are discussed in the following Sections.

1.1 Polymerization reactions.

1.2.2 Addition polymerization

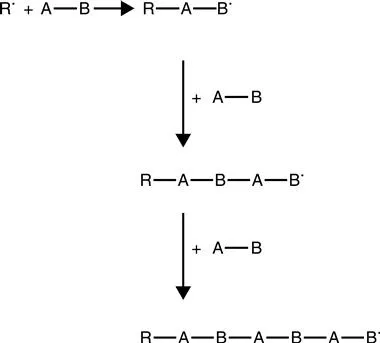

Addition polymers, also referred to as chain growth polymers, are normally formed by a chain addition reaction process. When an adjacent monomer molecule reacts with an active site of the monomer, chain addition is said to have occurred. Here, the active site is considered the reactive end of the polymer or monomer, which participates in the polymerization process. A schematic representation of a typical chain addition mechanism is shown in Fig. 1.2.

1.2 Schematics of a typical chain addition mechanism.

Commodity polymers, which are typically found in most consumer products, are usually formed by chain growth. These include polyethylene, polystyrene, and polypropylene. Polymerization in chain growth begins with a reaction between a monomer and a reactive species, which results in the formation of an active site. This chain growth polymerization occurs via four mechanisms: anionic, cationic, free radical, and coordination polymerization. These are the most common synthesis mechanisms for the formation of commodity polymers. The details are beyond the scope of this chapter, and can be found elsewhere.6

In addition to polymerization, the desired final product may be obtained through three principal steps: (1) initiation: how a polymerization reaction is started; (2) propagation: the polymerization is kept going by the ongoing addition of new monomers to the reactive end; and (3) termination: the means used to stop the reaction. The quality and characteristics of the desired polymer and the choice of the necessary monomer for the reaction process often dictate the choice of the polymerization path. In knowing and understanding the system and the components used in the polymerization process, it is possible to produce a polymer of required molecular weight and molecular weight distribution for specific products.

1.2.3 Condensation polymerization

Polycondensation is the term used to describe polymers formed as a result of reactions involving the condensation of organic materials in which small molecules are split out. In condensation polymerization, molecules of monomer and/or lower molecular weight polymers chemically combine, producing longer chains that are much higher in molecular weight. The polymers usually formed by this mechanism have two functional groups, where functionality is defined as the average number of reacting groups per reacting molecule. The kinetics of polycondensation is usually affected by ...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Contributor contact details

- Woodhead Publishing Series in Textiles

- Introduction

- Part I: General issues

- Part II: Spinning techniques

- Index