1.1.1 General characteristics

Depending on their internal structure, membranes can be classified as symmetrical or asymmetrical. Symmetrical membranes show uniform pore sizes in cross section. The pores of asymmetric membranes are usually smaller on the membrane surface. Composite membranes combine two different structures into the same membrane. The different layers can be either symmetrical or asymmetrical, with a distinct pore-size distribution, aspect ratio (ratio of pore sizes on the two faces of the membrane) and thickness. Multi-layer membranes have different membranes layered together, each of which is cast separately with the desired pore size and surface characteristics. The first layer is typically used as a pre-filter while the pore size of the second layer depends on the application.

From their morphological point of view, membranes can be divided into two large categories: dense and porous. Membranes are considered to be dense when the transport of components involves a stage of dissolution and diffusion across the material constituting the membrane. A membrane is denominated as porous when permeate transport occurs preferentially in the continuous fluid phase which fills the membrane pores.

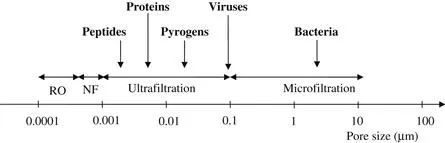

Membranes are usually classified accordingly to their average pore sizes (Figure 1.1). Microfiltration (MF) membranes typically have pore sizes on the order of 0.1–10 μm. Ultrafiltration (UF) membranes have pore sizes in the range of 0.001–0.1 μm and are capable of retaining species in the molecular weight range of 300–10,00,000 Da. Membranes designed specifically for virus filtration fall between these limits. Reverse osmosis (RO) membranes retain solutes, such as salts and amino acids, with molar mass below 1000 Da. Nanofiltration (NF) membranes retain solutes, such as small polypeptides, in the range of molar mass between 1000 and 3000 Da.

Figure 1.1 Approximate pore size ranges of different types of membranes, compared to dimensions of some components separated by membrane processes [1].

This article was published in Comprehensive Biotechnology, Second Edition, Vol. 2, C. Charcosset, Downstream Processing and Product Recovery/Membrane Systems and Technology, pp. 603–618, Copyright Elsevier (2011).

1.1.2 Organic membranes

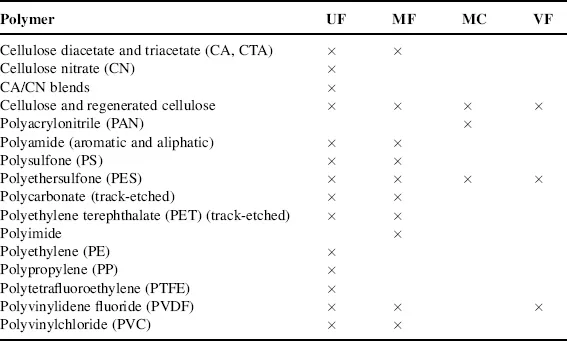

Common polymers used in commercial applications such as UF, MF, membrane chromatography and virus filtration are listed in Table 1.1. In addition, many polymers are grafted, custom-tailored, blended or used in the form of copolymers, to improve membrane properties, such as lower protein adsorption, higher flux, higher flux recovery ratio and lower membrane fouling. Common polymeric membranes are obtained by casting technologies, including air, immersion and melt casting. Other common techniques include track-etched membranes, membranes made by controlled stretching of films, composite membranes and nanofibrous membranes. They are briefly described below. Details on these various techniques are given in various references [2, 3].

Table 1.1 Common polymers used in commercial membrane manufacture

UF: ultrafiltration, MF: microfiltration, MC: membrane chromatography, VF: virus filtration

Casting technologies

Polymeric membranes are usually manufactured by a phase-inversion process. This technique involves preparing a casting solution consisting of one or more polymers in an appropriate solvent or solvent blend and possibly one or more non-solvents, surfactants and other additives such as inorganic salts. The polymeric membrane is prepared by causing this casting solution to undergo phase inversion, which involves the transformation of a homogeneous solution in which the polymer molecules are dispersed in the mixture of solvent(s) and non-solvent(s) into a porous membrane in which the polymer forms an interconnected matrix. The phase-inversion process is obtained (1) by removing solvent from a casting solution that contains non-solvent (wet casting); (2) by simultaneously removing solvent while adding non-solvent (dry casting) or (3) by cooling a casting solution that contains a latent solvent displaying only a limited ability to dissolve the polymer (thermally induced phase-separation [TIPS]) [4].

The wet casting process involves immersing the casting solution into a non-solvent bath that causes simultaneous loss of solvent and gain of non-solvent. The dry casting process entails evaporating sufficient solvent from a casting solution that initially contains some non-solvent. The TIPS process necessitates cooling a casting solution containing a solvent that can dissolve the polymer only at elevated temperatures. Combinations of these three fundamental phase inversion methods lead to hybrid processes. For example, wet casting may involve a precursor evaporation step that predisposes the interface of the casting solution to gel or vitrify. The thermally assisted evaporative phase separation process combines dry- and TIPS-casting, in which phase separation is caused by evaporative solvent loss coupled with temperature control. The vapour induced phase-separation process combines wet and dry casting whereby the casting solution is initially contacted with humid air (i.e. water is a non-solvent) followed by immersion into a non-solvent bath. Membranes from polymers with excellent chemical and thermal resistance can thus be produced, such as polyolefins, polyfluorocarbons and poly(ether ether ketone).

In recent years, several polymer blends have been used for the development of novel membranes with improved properties [5–7]. In addition, organic or inorganic additives as the third component to the blend polymers have been used to control the morphology and performance of membranes.

Studies were conducted by adding additives such as polyethylene glycol (PEG), hyperbranched polyglycerol (HPG) and polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) in the casting [8, 9]. Su et al. [8] prepared a series of amphiphilic poly(ethylene glycol)-graft-polyacrylonitrile (PEG-g-PAN) UF membranes with various molecular weights of PEGs by wet phase precipitation copolymerization using ceric(IV) ammonium nitrate as an initiator. All prepared PEG-g-PAN UF membranes have lower BSA adsorption, higher flux for protein solution, higher flux recovery ratio and lower membrane fouling during protein UF in comparison with the control PAN membrane. The authors concluded that these improved properties endow PEG-g-PAN membranes with potential applications in protein separation and purification. Sivakumar et al. [9] investigated the effects of PVP on CA/PS blend UF membranes and showed that an increase in the concentration of PVP in casting solution resulted in improved performance. Arthanareeswaran et al. [10] introduced sulfonated poly(ether ether ketone) (SPEEK) to modify a cellulose acetate (CA) membrane in order to obtain a CA/SPEEK blend UF membrane with improved performance. The same authors prepared PS and SPEEK blend membranes and characterized their UF performance [11]. Susanto and Ulbricht [12] prepared polyethersulfone (PES) UF membranes by a non-solvent-induced phase separation method using different macromolecular additives: PVP, poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) and poly(ethylene oxide)-b-poly(propylene oxide)-b-poly(ethylene oxide) (Pluronic®). Pluronic showed the best results in water flux and rejection of BSA.

Track-etched membranes

Track-etched membranes are made from thin polymeric films of polycarbonate, poly(ethylene terephthalate [PET]) or polyimide. Tracking is produced by bombardment of the film (10–20 μm thick) with a beam of high energy nuclear particles generated in a nuclear reactor. The interaction of the high energy beams leads to an array of linear, perpendicular tracks. The subsequent etching operation in a bath containing typically a hot NaOH solution, or...