Mathilde Almlund*, Angela Lee Duckworth**, James Heckman*,*** and Tim Kautz*

* Department of Economics, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637

** University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, PA 19104

*** University College Dublin, American Bar Foundation

Abstract

This chapter explores the power of personality traits both as predictors and as causes of academic and economic success, health, and criminal activity. Measured personality is interpreted as a construct derived from an economic model of preferences, constraints, and information. Evidence is reviewed about the “situational specificity” of personality traits and preferences. An extreme version of the situationist view claims that there are no stable personality traits or preference parameters that persons carry across different situations. Those who hold this view claim that personality psychology has little relevance for economics.

The biological and evolutionary origins of personality traits are explored. Personality measurement systems and relationships among the measures used by psychologists are examined. The predictive power of personality measures is compared with the predictive power of measures of cognition captured by IQ and achievement tests. For many outcomes, personality measures are just as predictive as cognitive measures, even after controlling for family background and cognition. Moreover, standard measures of cognition are heavily influenced by personality traits and incentives.

Measured personality traits are positively correlated over the life cycle. However, they are not fixed and can be altered by experience and investment. Intervention studies, along with studies in biology and neuroscience, establish a causal basis for the observed effect of personality traits on economic and social outcomes. Personality traits are more malleable over the life cycle compared with cognition, which becomes highly rank stable around age 10. Interventions that change personality are promising avenues for addressing poverty and disadvantage.

1 Introduction

The power of cognitive ability in predicting social and economic success is well documented.2 Economists, psychologists, and sociologists now actively examine determinants of social and economic success beyond those captured by cognitive ability.3 However, a substantial imbalance remains in the scholarly and policy literatures in the emphasis placed on cognitive ability compared to other traits. This chapter aims to correct this imbalance. It considers how personality psychology informs economics and how economics can inform personality psychology.

A recent analysis of the Perry Preschool Program shows that traits other than those measured by IQ and achievement tests causally determine life outcomes.4 This experimental intervention enriched the early social and emotional environments of disadvantaged children of ages 3 and 4 with subnormal IQs. It primarily focused on fostering the ability of participants to plan tasks, execute their plans, and review their work in social groups.5 In addition, it taught reading and math skills, although this was not its main focus. Both treatment and control group members were followed into their 40s.6

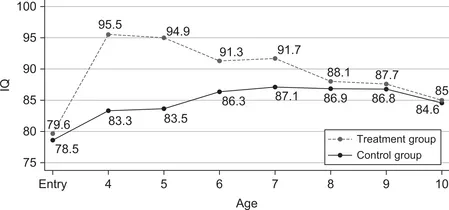

Figure 1.1 shows that, by age 10, the mean IQs of the treatment group and the control group were the same. Many critics of early childhood programs seize on this and related evidence to dismiss the value of early intervention studies.7 Yet on a variety of measures of socioeconomic achievement, the treatment group was far more successful than the control group.8 The annual rate of return to the Perry Program was in the range 6–10% for boys and girls separately.9 These rates of return are statistically significant and above the returns to the US stock market over the postwar period.10 The intervention changed something other than IQ, which produced strong treatment effects. Heckman, Malofeeva, Pinto, and Savelyev (first draft 2008, revised 2011) show that the personality traits of the participants were beneficially improved in a lasting way.11 This chapter is about those traits.

Personality psychologists mainly focus on empirical associations between their measures of personality traits and a variety of life outcomes. Yet for policy purposes, it is important to know mechanisms of causation to explore the viability of alternative policies.12 We use economic theory to formalize the insights of personality psychology and to craft models that are useful for exploring the causal mechanisms that are needed for policy analysis.

We interpret personality as a strategy function for responding to life situations. Personality traits, along with other influences, produce measured personality as the output of personality strategy functions. We discuss how psychologists use measurements of the performance of persons on tasks or in taking actions to identify personality traits and cognitive traits. We discuss fundamental identification problems that arise in applying their procedures to infer traits.

Many economists, especially behavioral economists, are not convinced about the predictive validity, stability, or causal status of economic preference parameters or personality traits. They believe, instead, that the constraints and incentives in situations almost entirely determine behavior.13 This once popular, extreme situationist view is no longer generally accepted in psychology. Most psychologists now accept the notion of a stable personality as defined in this chapter.14 Measured personality exhibits both stability and variation across situations.15

Although personality traits are not merely situation-driven ephemera, they are also not set in stone. We present evidence that both cognitive and personality traits evolve over the life cycle, but at different rates at different stages. Recently developed economic models of parental and envir...