eBook - ePub

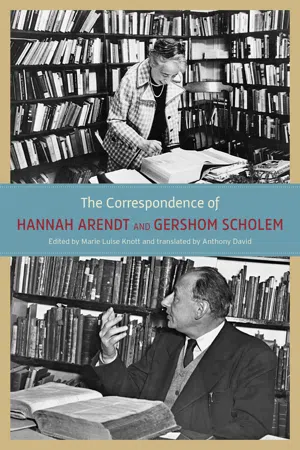

The Correspondence of Hannah Arendt and Gershom Scholem

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Correspondence of Hannah Arendt and Gershom Scholem

About this book

Few people thought as deeply or incisively about Germany, Jewish identity, and the Holocaust as Hannah Arendt and Gershom Scholem. And, as this landmark volume reveals, much of that thinking was developed in dialogue, through more than two decades of correspondence.

Arendt and Scholem met in 1932 in Berlin and quickly bonded over their mutual admiration for and friendship with Walter Benjamin. They began exchanging letters in 1939, and their lively correspondence continued until 1963, when Scholem's vehement disagreement with Arendt's Eichmann in Jerusalem led to a rupture that would last until Arendt's death a dozen years later. The years of their friendship, however, yielded a remarkably rich bounty of letters: together, they try to come to terms with being both German and Jewish, the place and legacy of Germany before and after the Holocaust, the question of what it means to be Jewish in a post-Holocaust world, and more. Walter Benjamin is a constant presence, as his life and tragic death are emblematic of the very questions that preoccupied the pair. Like any collection of letters, however, the book also has its share of lighter moments: accounts of travels, gossipy dinner parties, and the quotidian details that make up life even in the shadow of war and loss.

In a world that continues to struggle with questions of nationalism, identity, and difference, Arendt and Scholem remain crucial thinkers. This volume offers us a way to see them, and the development of their thought, anew.

Arendt and Scholem met in 1932 in Berlin and quickly bonded over their mutual admiration for and friendship with Walter Benjamin. They began exchanging letters in 1939, and their lively correspondence continued until 1963, when Scholem's vehement disagreement with Arendt's Eichmann in Jerusalem led to a rupture that would last until Arendt's death a dozen years later. The years of their friendship, however, yielded a remarkably rich bounty of letters: together, they try to come to terms with being both German and Jewish, the place and legacy of Germany before and after the Holocaust, the question of what it means to be Jewish in a post-Holocaust world, and more. Walter Benjamin is a constant presence, as his life and tragic death are emblematic of the very questions that preoccupied the pair. Like any collection of letters, however, the book also has its share of lighter moments: accounts of travels, gossipy dinner parties, and the quotidian details that make up life even in the shadow of war and loss.

In a world that continues to struggle with questions of nationalism, identity, and difference, Arendt and Scholem remain crucial thinkers. This volume offers us a way to see them, and the development of their thought, anew.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Correspondence of Hannah Arendt and Gershom Scholem by Hannah Arendt,Gershom Scholem, Marie Luise Knott, Anthony David in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9780226487618Subtopic

Philosopher BiographiesPart One

The Letters

Letter 1

From Arendt

68 rue Brancion, Vaugirard 38-07

May 29, 1939

Dear Scholems,

It’s become almost a scandal that I’m just today getting around to replying to your two letters that were such a delight for me.1 Since receiving them, first of all my mother arrived; second came my furniture; and third my library. The fourth, fifth, and sixth things that have happened here is that the good Lord in heaven, in the form of the Central Bureau, has blessed me with a profession; and as everyone knows, every gift from heaven has its shadow side.2 This shadow side, for me, is that I’m not managing to get a bit of work done.

As regards Rahel, I’ve naturally given wide berth to any sort of hagiography.3 I wanted to describe bankruptcy, though admittedly a bankruptcy that was historically necessary, and possibly even redemptive. I would like it if, with all their criticism, readers would glean out of the final two chapters a kind of vindication.4 These days this is especially important because every ignorant upstart thinks he can heap scorn onto assimilated Judaism. The book was written before Hitler. The final two chapters, which I wrote here, hardly change the book at all.

If I had only known the kind of material Schocken has in his collection!5 It was terribly annoying for me to be dependent on my excerpts from so many years ago. If there is any chance at all to get it published, I would be very grateful if you could make the connection for me. Naturally, you can keep the manuscript.6 And, of course, I would be thrilled if you want to stir Schocken’s interest in the book.

I’m really worried about Benji.7 I tried to line up something for him here but failed miserably.8 At the same time, I’m more than ever convinced how vital it is to put him on secure footing so he can continue his work. As I see it, his work has changed, down to his style. Everything strikes me as far more emphatic, less hesitant. It often seems to me as if he is only now making progress on the questions most decisive for him. It would be awful if he were to be prevented from continuing.

One can hardly imagine what’s going on back in Germany. For most of us here, it goes without saying that things are really lousy here, in particular as well as in general. How is your work coming along? What’s Fanja up to? I would be elated if the two of you could find some reason to make another trip to Europe, because I don’t see much chance for me to be a tour leader over there.9

Blücher sends his warmest greetings. Please don’t be annoyed at my tardy reply, and don’t be such a stranger. I’d like to hear from you again soon.

Yours,

Hannah

Letter 2

From Arendt

Montauban

October 21, 1940

Dear Scholem,

Walter Benjamin took his own life on September 29 in Portbou on the Spanish frontier. He had an American visa, but on the twenty-third the only people the Spanish allowed to pass the border were those with “national” passports.1 I don’t know if this letter will reach you. In the past weeks and months I had seen Walter several times, the last time being on September 20 in Marseilles. The report of his death took nearly four weeks to reach both his sister and us.2

Jews are dying in Europe and are being buried like dogs.

Yours,

Hannah Arendt

Letter 3

From Fanja and Gershom Scholem

July 17, 1941

Jerusalem

Dear Hannah Arendt,

I’m so glad you are finally able to breathe freely again, and I hope to hear from you very soon. In your last letter you wrote about Benjamin’s death.

I hardly need to tell you how Gerhard took the news. Do you remember the conversation we had about the relationship between Walter and Gerhard? I recall every word. It breaks my heart to think that I never saw the man.1

It was so lovely in Paris, and the memories of this wonderful city are bound up with memories of you. You were so kind to us. We are still living well here, and we hope for victory. Your friend Jonas, now with an artillery unit, is busy shooting down enemy airplanes. He is so proud of being a soldier, and he’s a bit more childish than he was when he was occupied with Gnosticism.2 Gerhard still wants to write to you today, so I will sign off. Take care of yourself and think about us.

Your Fanja Scholem

And greetings to Kurt Blumenfeld.3

My dear friend,

Mrs. Zittau tells us you’ve arrived safely in New York—at last one piece of good news amid all the gloom.4 Oh, the two of us have so much to talk about, and yet who knows when we’ll get the chance! We’ll just have to hack our way through this mountain of darkness, if I can say so. One senses the meaning of apocalyptic prospects in one’s own flesh and blood. Please write soon—it took three weeks for your letter to arrive from last October. It was the first report I received of Walter’s death. I wish you had given me a return address: I wasn’t able to reply without one. Please pay a visit to my friend Shalom Spiegel5 at the Jewish Institute of Religion (New York, 309 West 93rd Street). Tell him I sent you. He’s a fantastic fellow, and both Blücher and you should become friendly with him.6

Warmest greetings, from your Gerhard Scholem

Forgive me for this awfully bad ink!

Letter 4

From Arendt

317 West 95th Street, New York

October 17, 1941

Dear Scholem,

Miriam Lichtheim gave me your address and relayed your greetings. While I hope that even without her I would have gotten around to writing you, I have to admit she gave me a useful nudge.

Wiesengrund tells me that he had sent to you a detailed report of Benjamin’s death.1 Here in New York I’ve heard some not unimportant details for the first time. It may be that I’m not all that qualified to give an account of his death because I had considered such a possibility so far-fetched that for weeks after he died I dismissed the entire business as being no more than immigrants’ gossip. All this despite the fact that especially in the last few years and months we were very close friends and saw one another on a regular basis.

With the outbreak of war we were all together for a summer break in a small French village near Paris. Benji was in excellent shape. He had finished part of his work on Baudelaire and was prepared, justifiably I think, to do some extraordinary things.2 The outbreak of war immediately terrified him beyond all measure. Fearing bombardments from the air, on the first day of the general mobilization he left Paris for Meaux. Meaux was a well-known center for the mobilization, with a militarily very important airport and train station, which made it a hub for the entire deployment of forces. Of course, the result was that from the start one air-raid alarm followed the next; rather aghast, Benjamin at once made his way back to Paris. He came back just in time to get himself duly rounded up. In the temporary camp at Colombes, where my husband3 talked to him at length, he was rather depressed, and for good reason, of course. At once he entered into a kind of asceticism. He stopped smoking, gave away all his chocolate, refused to wash himself or shave, and more or less refused to move a limb. Upon arrival in the final camp he wasn’t feeling all that bad. He had a bevy of young boys around him; they liked him a lot, and were keen to learn from him and swallowed every word he said.4 By the time he returned in the middle or end of November, he was more or less glad to have had the experience. His initial panic was gone entirely. In the months that followed he wrote his historical-philosophical theses, of which I have been told he sent you a copy, too.5 As you have seen, he was on the spoors of a number of new things, though at the same time he was undeniably fearful of the opinion of those at the Institute.6 You surely know that before the war he received word from the Institute that his stipend was no longer secure and that he should look around for something else.7 That caused him a lot of anxiety, even if he wasn’t all that convinced of the seriousness of the Institute’s suggestion. Which didn’t improve things, and if anything it made the matter all the more disagreeable for him. The outbreak of war took care of that anxiety. Still, he wasn’t all that comfortable with the reaction of his most recent, downright unorthodox theories. In January one of his new young friends from the camp, who happened to have been a student of my husband’s, killed himself, mostly for personal reasons.8 This suicide preoccupied Benjamin to an extraordinary extent; and in all the discussions about it, with a truly passionate vehemence, he stood with those who defended the young man’s decision. In spring 1940, with heavy hearts, we all made our way to the American consulate. Even though we heard the same thing, that we would have to wait between two and ten years before our quota number came up, the three of us took English lessons.9 None of us took it all that seriously. Benjamin had just one wish: to learn enough of English to say that he absolutely didn’t like the language. And he succeeded. His horror at America was indescribable, and apparently already then he told friends that he preferred a shorter life in France to a longer one in America.

This all came to a quick end. From the middle of April, those of us under the age of 48 who had been released from internment were examined for our suitability for military fatigue duty. Fatigue duty was really just another word for internment with forced labor; and measured against the first round of internment, in most cases it was worse. Everyone—that is, everyone but Benji—had no doubt he would be declared unfit for service. In those days he was awfully agitated, and on a number of occasions he told me he wouldn’t be able to play along once again. Of course, he was declared unfit. Independent of all of this, in the middle of May the second and far more systematic internment took place. You must know about this. As if a miracle, of the three people spared the internment, Benji was one. Due to administrative chaos, he nevertheless could never know whether, or for how long, the police would accept an order from the Interior Ministry. Would the police simply arrest him? Personally, I had no contact with him at the time because I was interned.10 Friends told me, however, that he didn’t dare venture out on the streets any longer, and he was living in constant panic. He managed to get on the last train leaving Paris. He took only a small suitcase with two shirts and a toothbrush. As you know, he traveled to Lourdes. As soon as I got out of Gurs in the middle of June, by chance I, too, headed to Lourdes, where I stayed for a few weeks at his instigation. This was the time of defeat, and after a few days the trains stopped running. No one knew what had happened to families, husbands, children, and friends. Benji and I played chess from morning to evening, and between games we read newspapers, to the extent we could get our hands on them. Everything was as fine as could be—until the ceasefire terms were published, along with the infamous extradition clause.11 But even then I can’t say that Benjamin fell into a full-blown panic, even if we were both feeling anxious. Mind you, when news re...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction: “Why Have We Been Spared?”

- Part One: The Letters

- Part Two: Documents

- Editorial Remarks

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index of Persons

- List of Abbreviations

- Gallery