eBook - ePub

Oracles of Empire

Poetry, Politics, and Commerce in British America, 1690-1750

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This innovative look at previously neglected poetry in British America represents a major contribution to our understanding of early American culture. Spanning the period from the Glorious Revolution (1690) to the end of King George's War (1750), this study critically reconstitutes the literature of empire in the thirteen colonies, Canada, and the West Indies by investigating over 300 texts in mixed print and manuscript sources, including poems in pamphlets and newspapers.

British America's poetry of empire was dominated by three issues: mercantilism's promise that civilization and wealth would be transmitted from London to the provinces; the debate over the extent of metropolitan prerogatives in law and commerce when they obtruded upon provincial rights and interests; and the argument that Britain's imperium pelagi was an ethical empire, because it depended upon the morality of trade, while the empires of Spain and France were immoral empires because they were grounded upon conquest. In discussing these issues, Shields provides a virtual anthology of poems long lost to students of American literature.

British America's poetry of empire was dominated by three issues: mercantilism's promise that civilization and wealth would be transmitted from London to the provinces; the debate over the extent of metropolitan prerogatives in law and commerce when they obtruded upon provincial rights and interests; and the argument that Britain's imperium pelagi was an ethical empire, because it depended upon the morality of trade, while the empires of Spain and France were immoral empires because they were grounded upon conquest. In discussing these issues, Shields provides a virtual anthology of poems long lost to students of American literature.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Oracles of Empire by David S. Shields in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

The British Empire and the Poetry of Commerce

Commerce Navigation and Trade ought to be encouraged and accounted the most honourable of all professions, for that it brings the greatest Morall Blessings to Mankinde, for what one Country wants is supply’d from another that abounds and anciently men were Esteem’d honourd & dig nify’d according to the benefits and commodities their Country had recvd from them—War is destructive to humane nature, physick is of necessity, law is for the depravation of manners. Philosophy is but an idle Speculation, the Mathematicks & Machinicks wou’d be useless w{i}thout Trade & commerce, to dispose of ye several comodities that imploy the Industrious and ingenious of all ages{.} Solomon shew’d more wisdom and acquir’d more Glory by sending his Ships to Ophir than his father David did by all his conquests and the Citys and inhabitants of Tyre & Sydon are by the prophet call’d the crowning Cities whose merchants are princes & whose traffickers are the honourable of the earth, only in respect of their trade.

—THOMAS WALDUCK, Barbados, 1710

1

The Literary Topology of Mercantilism

During the first decades of the seventeenth century, Spanish imperialists conceived and established national economic self-sufficiency—autarky—by organizing a global network of subordinate principalities, colonies, territories, and zones of domination. The desire for self-sufficiency arose from political ambitions of ancient vintage, a legacy of the great classical empires. The global economic modus was Spain’s creation. Or perhaps it was an English innovation, for the first theoretician of autarky in Spain was the English mariner, Antony Sherly, whose Peso Político de Todo el Mundo (1622), addressed to the duke of Olivares, laid out on the widest possible canvas the method by which the resources of the world might be exploited to the benefit of Philip III’s imperial dominion.1 Sherly’s vision, composed out of practical considerations for the imposition of economic coherence upon the welter of territories that had fallen under Spanish sway, became, during the middle decades of the seventeenth century, the imperial program of his native country. There in a mutated form it became the doctrine of imperial administration called mercantilism.

Mercantilism was the economic policy that governed the commerce of the First British Empire, which unraveled with the American Revolution. This policy assumed an extensive protected market wherein the imperial center (“the metropolis”) produced manufactured goods and exchanged them for raw resources to an ever-expanding network of trading outposts and colonies. Imperial projectors envisioned a global trading network producing limitless supplies of gold and silver. The Board of Trade in London administered the trade, restricting exchanges between colonies and foreign states, and between colony and colony. To compensate for the lack of free trade and the privilege granted the central metropolis, the mercantile scheme ensured a secure market for all goods produced in the provinces.2 To keep the system firmly in place, the British government inhibited the development of a manufacturing economy in the hinterlands.3

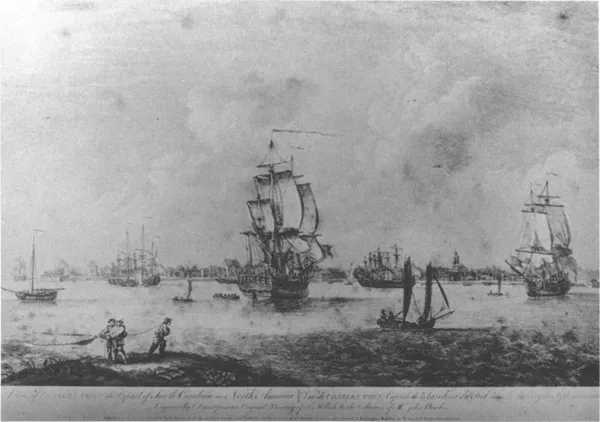

A view of Charles Town the Capital of South Carolina in North America, 1738. Engraving by C. Canot after a painting by T. Mellish. Published in the year that James Kirkpatrick, the laureate of British American mercantilism, left Charleston, Canot’s engraving depicts the metropolis of South Carolina as a center of trade. Viewed from the perspective of the imperial center, Charleston appears over an expanse of water as the destination of merchantmen bearing the union jack. Each of British America’s port cities was conventionally depicted from a mercantilist viewpoint until the 1770s. Reproduced courtesy of the South Carolina Historical Society.

Mercantilism came into being during the early seventeenth century less as a coherent economic ideology than as a concretion of ideas and practices.4 When discussed, it lent itself more readily to symbolic representation than to elucidation as a scheme of economic principles. Indeed it was only with Adam Smith’s critique of mercantilism in The Wealth of Nations that a comprehensive, systematic account of mercantilism was assayed in economic terms.5 During the seventeenth century, poetry became an effective vehicle for popularizing the iconology of imperial trade. Animated by British patriotism, poets first employed mercantile images and themes during the Anglo-Dutch wars of the seventeenth century. Dryden perfected the mode in his poetry on the affairs of state.6 British American poets grasped its utility during the decade following the Glorious Revolution. By the 1720s its imagery dominated American verse about empire.

An iconology—a scheme of symbolism employed in literature and graphic arts—evolved to illustrate the mercantile program.7 A brief survey of mercantile topoi will introduce more detailed investigations of the imagery of British American empire.

We begin with the most potent and comprehensive image—the “empire of the seas.” The doctrine of a maritime empire maintained by global control of the trading lanes derived from English musings on the rise of the Dutch to trading preeminence.8 Raleigh and John Smith both distilled lessons from the Dutch experience, which they then applied to their colonial ventures. Furthermore, Bacon explored the role of maritime dominion in the expansion of empire in his Advancement of Learning.9 Bacon argued that trade rather than territory constituted the more peaceful and economical way to national prosperity. Consequently, colonization efforts should be undertaken not to conquer territory from native populations (Bacon explicitly rejected the imperial projects of Spain in the New World and of Britain in northern Ireland), but to establish secure bases from which to dominate commerce with a people.

The notion that maritime dominion should be global came about largely as a result of the religious interpretation of the economy of providence. After the discovery of the New World, theologians speculated about God’s intention in distributing commodities about the earth in such a way that no single country possessed a sufficiency of what it needed or desired. They concluded that commerce taught man his need for his fellow being. Anne Bradstreet stated the belief in the last of her meditations: “God hath by his prouidence so ordered, that no one Covntry hath all Commoditys within it self, but what it wants, another shall supply, that so there may be a mutuall Commerce through the world.”10

England asserted mastery over this commerce (thereby usurping God’s intention) in the name of an atavistic ambition—a revival of the ancient urge to seize glory by world domination.11 Nursed by generations of classically educated enterprisers, the atavistic myth proclaimed London the New Rome and Britain’s expanding territories the new Roman empire. Just as the old Roman imperium justified world dominion by promoting the benefits of the Pax Romana, the New Rome rationalized its empire of the seas by declaring the benefits of “the Arts of Peace” resulting from British superintendence of world trade.

Britain devised an elaborate apologetic for its mercantile empire. It promoted the benefit of British laws, much as the Romans did the imperium. It prophesied the rising glory of London (Augusta) and its provincial capitals in terms of both material wealth and aesthetic refinement; the prophetic myth is generally termed the translatio studii.12 It featured a comparison to demonstrate the ethical animus of Britain’s empire: the morality of British trade was held up against the depravity of Spanish conquest, a depravity the conquistadors confessed in the Black Legend; or it was contrasted to the “Gallic perfidy” of France.

The mystique of British law suffused the rhetoric of mercantilism. This mystique manifested itself in the translatio libertatis, the myth of the westward spread of Britain’s legal liberties. The legend found its quintessential expression in James Thomson’s poem Liberty (1736), of which the American poet and imperial administrator, Dr. Thomas Dale, said, “I have seen some parts of Thompson’s Liberty, I take him to be the Homer of our Island.”13

The legal mystique also found expression in the cult of the contract. The morality of British trade derived primarily from its grounding in contract. Over the course of the eighteenth century, imperial morality mutated as the understanding of the nature of the contract evolved. At first, North America’s Indian tribes were envisioned as the superintendents of New World resources. The benefits of European civilization would be bestowed upon the Indians in return for the medicines, metals, and foodstuffs they controlled.14 As decades passed the contract altered, becoming an exchange of native land for cloth goods, metalwares, and alcohol. This mutation marked the shift away from a purely mercantile vision of empire to a mixed model in which expanding colonial bases consolidated ever-greater expanses of territory, obtained by purchase rather than by conquest. The colonies became Britain’s primary partners in the trading contract, while the native populations became ancillary concerns. While many writers commented on this shift, Rev. William Smith in Indian Songs of Peace offered the most comprehensive literary exposition of the revised imperial program.15 Written instruments stood warrant over exchanges between the metropolis and both colonists and Indians, testifying to the autonomy of the trading partners; these were the provincial charters on one hand, and the Indian treaties on the other.

Entrepreneurs and poets imagined the global economy in terms of profusion. Common belief held that each land harbored a surplus of some commodity that could be exchanged. In promotional literature colonial territories invariably appeared as cornucopias of commodity or potential commodity. Indeed, this article of faith proved so potent that Rev. James Sterling of Maryland in his Epistle to Arthur Dobbs, the projector of the Northwest Passage, imagined the arctic wastes harboring marketable goods ripe for exploitation.

Say; Necessaries grow in steril Lands,

To answer simple Nature’s prime Demands.

Ev’n there some Superfluities are made;

That Arts and Elegance may spring from Trade.16

The poets of commerce conceived of a world blessed with a superfluity of products. Furthermore, as the implications of trade impre...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction. The Issue of Empire in the Literary Self-Understanding of British Americans

- Part One. The British Empire and the Poetry of Commerce

- Part Two. The Paper Wars Over the Prerogative

- Part Three. The Rhetoric of Imperial Animosity

- Notes

- Bibliography of Primary Sources

- Index