- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In Fire under the Ashes, John Donoghue recovers the lasting significance of the radical ideas of the English Revolution, exploring their wider Atlantic history through a case study of Coleman Street Ward, London. Located in the crowded center of seventeenth-century London, Coleman Street Ward was a hotbed of political, social, and religious unrest. There among diverse and contentious groups of puritans a tumultuous republican underground evolved as the political means to a more perfect Protestant Reformation. But while Coleman Street has long been recognized as a crucial location of the English Revolution, its importance to events across the Atlantic has yet to be explored.

Prominent merchant revolutionaries from Coleman Street led England's imperial expansion by investing deeply in the slave trade and projects of colonial conquest. Opposing them were other Coleman Street puritans, who having crossed and re-crossed the ocean as colonists and revolutionaries, circulated new ideas about the liberty of body and soul that they defined against England's emergent, political economy of empire. These transatlantic radicals promoted social justice as the cornerstone of a republican liberty opposed to both political tyranny and economic slavery—and their efforts, Donoghue argues, provided the ideological foundations for the abolitionist movement that swept the Atlantic more than a century later.

Prominent merchant revolutionaries from Coleman Street led England's imperial expansion by investing deeply in the slave trade and projects of colonial conquest. Opposing them were other Coleman Street puritans, who having crossed and re-crossed the ocean as colonists and revolutionaries, circulated new ideas about the liberty of body and soul that they defined against England's emergent, political economy of empire. These transatlantic radicals promoted social justice as the cornerstone of a republican liberty opposed to both political tyranny and economic slavery—and their efforts, Donoghue argues, provided the ideological foundations for the abolitionist movement that swept the Atlantic more than a century later.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fire under the Ashes by John Donoghue in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Reformation Work

. . . And if things be not shortly reformed, [the people] will work a reformation themselves.

—Anonymous billet, Coleman Street Ward, London, June 16281

AS IN all London pubs worthy of the name, a few rounds at the Nag’s Head could transform even the quietest drinkers into silver-tongued orators, inspired with the kind of eloquence that can only be found at the bottom of a brimming tumbler. But on that day in 1639, the spirit moving the man at the bar with the booming voice was not John Barleycorn’s. The cobbler Samuel How had come to preach and not to drink, and judging by the crowd buzzing at his elbow, the veteran of the “King’s forces land and sea” had learned his latest trade very well.2 Climbing into his impromptu pulpit, a wooden cask refitted for the occasion, How quoted Acts 10:34 and proclaimed to the assembled that “God respects no man’s person . . .” The enigmatic phrase, as the cobbler explained, meant that the Lord had no regard for the man-made distinctions of social class that justified the rule of the rich and eminent over the poor and the weak.3 Punctuating a rolling passage with a quote from 1 Corinthians 1:29, the “mechanic preacher” went on to warn that “no flesh shall glory,” a caution to the wealthy and well-educated that their achievements in this world did not guarantee glory in the next. How aimed these barbs straight at his invited guest, the Cambridge MA and noted puritan divine John Goodwin.4

As the vicar of St. Stephen’s Church, Goodwin did not have to travel far that day to hear How hold forth at the Nag’s Head, for both the pub and the parish could be found in Coleman Street Ward in the City of London. Londoners had long regarded the neighborhood as a kind of seminary for zealots of the puritan persuasion, a place where wild-eyed Bible-thumpers instructed the faithful in their strange and strident gospels. With a leathery, old cobbler preaching out of a barrel in a smoke-filled barroom, the scene at the Nag’s Head hardly dispelled these notions. Taking his text from the twelfth chapter of Paul’s letter to the Romans, How proclaimed that “God’s ordinary way is among the foolish and weak and vile, so that when as the wise, rich, noble and learned come to receive the gospel, they then come to make themselves equal with them of the lower sort, the foolish, vile and unlearned; for those be the true heirs of it . . .”5 As a former soldier and sailor who had turned to mending shoes, How had run the gauntlet of some of early modern England’s least lucrative occupations; in preaching the Word to a Coleman Street audience consisting mostly of “the commonality” or the working poor, How personified this upside-down vision of the Christian kingdom.6 Unlike Goodwin and the other ordained ministers among the hundred or so who packed the pub that day, How did not pretend to be above or even different from the commonality, for as a cobbler he was truly one of them. Through the leveling power of the Holy Spirit, How hoped that the clergy would turn away from the pride of their learned wisdom and toward the inspired humility of the London poor, to find the courage and compassion to purge rather than serve the antichrist that they condemned.7 Samuel How went to prison for his sermon and died in jail in September 1640, hailed by his friends as a martyr murdered by the enemies of reformation.8 But while How’s aged and work-worn body proved too weak for prison, we will see later how the strength of his spirit helped to inspire the English Revolution. How’s story calls to mind another rebel shoemaker, the American Revolution’s George Robert Twelves Hewes, who like How had once sailed the seas and shouldered a soldier’s musket. As the historian Alfred F. Young once wrote about George Hewes, Samuel How “was a nobody who became a somebody in the Revolution and, for a moment near the end of his life, a hero.”9

As How’s set-to with Goodwin attests, before the English Revolution the godly made Coleman Street a central venue for interpuritan disputation as well as militant Protestant organization, all of which made religious issues political, economic, and social ones as well. Because it was the seventeenth century, interpuritan discord never revolved purely around religion. Evolving within the turbulent contexts of state centralization and the rapid economic and demographic changes sweeping early modern England, interpuritan disputation also became a catalyst for popular politicization and class-conscious10 social criticism and reform. For many well-to-do saints, mastering the poor, seditious, and morally degenerate elements of the commonality became part of their own wide-ranging reformation project, although commoners inside and outside the godly fold would challenge such efforts by “work[ing] their own reformation.” As a result, from the late sixteenth century through the middle of the next, the desire for reformation, to transform the world in the image of divine purity and justice, ranged far beyond the realm of religion and remained a matter of ideological conflict rather than cohesion for the diverse echelons within the godly camp.

Reformation work also took the saints far from home in the early seventeenth century, when Coleman Street puritans emerged at the forefront of English commercial and colonial expansion in the Atlantic world. Inspired by the lure of profits and the ideals of English humanism, puritans from the ward and their godly partners spearheaded privateering ventures and joint stock companies that created colonies and trading networks in New England, the Chesapeake, and the West Indies. As an alternative to the crown’s seemingly weak stance against Catholic Spain, the saints promoted these colonial projects as militant Protestant, civic solutions to the manifold crises facing the English nation at home and abroad. Their efforts created an English Atlantic of largely autonomous colonial commonwealths; a generation later, England’s Revolutionary government, led by many of the same colonial projectors, would try to consolidate these scattered Atlantic enclaves into a mighty and prosperous empire, a project that, as we will see, only exaggerated the ideological discord that radicals like Samuel How had helped to excite within the ranks of those who would lead England into revolution.

AS one of the hundreds of thousands of desperately poor people living in London in December 1619, Walter Hill embodied the most tragic features of life in the booming metropolis. As a young, homeless child, Hill wandered the streets of a City whose resident gentry reaped rising rents and woolens profits from their newly enclosed country estates.11 Members of London’s mercantile elite looked outside England for their riches and expanded their fortunes in proportion to the reach of their global ventures. Predictably, wealth accumulated rapidly at the top. The city’s population grew as well, but mostly at the bottom, doubling in the seventy years following the turn of the seventeenth century so that London became Europe’s largest city, a sprawling metropolis of half a million people.12 While higher birth rates can help account for the growing English population, they alone do not explain England’s appalling levels of poverty and the destitution of London’s swelling masses: for such an explanation we must consider how those who owned the English economy actually organized it. When John Winthrop, a future founder of the Bay Colony, took note of the suffering of poor people in the City like young Walter Hill, he saw a social crisis “groaning for reformation.” “Why,” asked this Suffolk puritan in 1623, “meet we so many wandering ghosts in the shape of men, so many spectacles of misery in all our streets, our houses full of victuals, and our entries of hunger starved Christians? Our shops full of rich wares and under our stalls lie our own flesh in nakedness?”13 Historians have borne out the reality behind Winthrop’s lament. According to the research of the historian Paul Slack, the numbers of people on poor relief increased four times over and above the rate of population increase during the Tudor/Stuart era.14

When Winthrop wondered aloud about the causes of poverty, he posed rhetorical questions—he knew that vagrants did not drop from the sky. The poverty of people like Walter Hill was produced, as Winthrop later wrote, largely by the greed of opportunistic, enclosing, and rack-renting gentry. Eager to capitalize on profits from foodstuffs and the woolens trade, landlords enclosed common lands for grazing, converted other commons to private fields for arable agriculture, dispensed with feudal land tenures, and paid poverty wages to rural laborers, who emerged as a new class during the early modern period due in large part to these changes. Rural wage laborers had come to make up about half the English population at this time, although the roads, towns, and cities were also choked with homeless wanderers, made so in many cases through the so-called economic improvements undertaken by landlords. Rising rents, soaring food prices, and periodic declines in trade and agricultural prices: the personal impact of impersonal markets that operated increasingly on national and international scales hurt rural workers as well as the small producers of England’s towns, villages, and cities. The English poor surged forth from this unsettling yet profitable confluence of market forces, made worse in times of dearth and disease, taking to the roads in search of work in unprecedented numbers in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.15

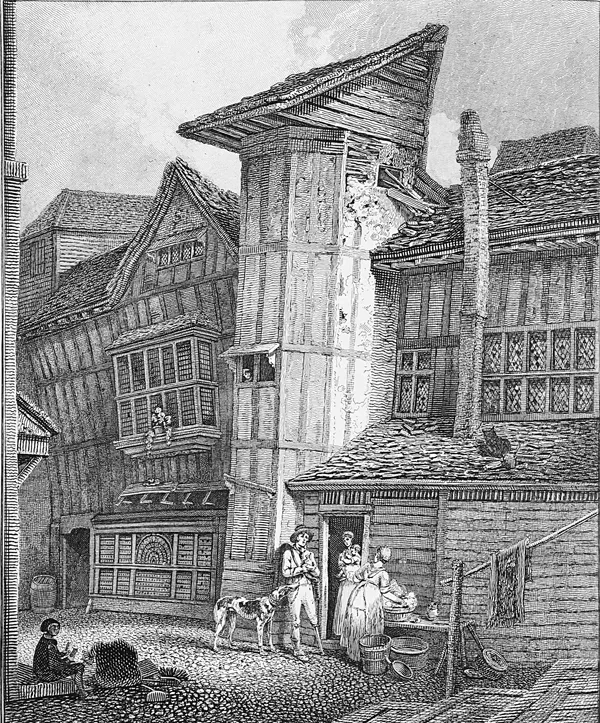

Arriving in London, poor newcomers who could afford it settled in the backstreets. The novelist Daniel Defoe, whose family owned a warehouse in Coleman Street Ward, noted that the neighborhood “was, and is still remarkable particularly, above all the parishes in London, for a great number of alleys and thoroughfares, very long,” where people on the economic margins crowded into rickety, jerry-rigged tenement buildings. These tenements lined the alleys that traversed Coleman Street proper in a series of long, narrow, crooked passages that led to a warren of courtyards and lanes. The most important of these byways were Swann Alley, Bell Alley, and White Alley. One account described Swann and Bell Alleys as “so narrow that a horse and cart could not pass through.” The narrowness of the streets, coupled with the lack of open space within the Square Mile, forced Londoners to build up when they added on, and often three and four stories were piled atop the original timber-framed daub-and-wattle dwellings, with each addition jutting several feet farther into the street. Seventeenth-century London poll taxes illustrate how the burst of tenement building affected the back lanes of Coleman Street Ward, which, like London’s other subterranean warrens, grew steadily more crowded in the decades before the Revolution. Between 1603 and 1637, the number of buildings in the ward tripled, with 176 new multi-tenant houses sprouting up in the midst of 102 preexisting single-family dwellings. One can easily imagine the swelling concourse of the poor streaming through the City streets. There, as a contemporary noted, “posts are set up of purpose to strengthen the houses, lest with jostling one another” the crowds of people “should shoulder them down.” Lost in these crowds were many children like Walter Hill who, having entered the ranks of the destitute after being orphaned or abandoned, had not even a hovel to call home. Home was in the streets.16

The descent of impoverished youngsters like Hill contrasted starkly with the ascent of self-made men like the wealthy Maurice (or Morris) Abbot, who like others of his station, lived on Coleman Street proper, “a fair and large street, on both sides builded with diverse fair houses.” While Abbot and those from his class typed Hill and other indigent children as wild and masterless threats to the commonwealth, they entertained high opinions of themselves as the founding fathers of England’s economic expansion. As Abbot’s friend the East India Company member Dudley Digges wrote in 1615, within a “few years . . . well-minded merchants . . . like Hercules in the cradle” would make England “a staple of commerce for all the world . . . to advance the reputation and revenue of the Commonwealth.” Hercules, as the historians Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker have written, “served as a model for the exploration, trade, conquest, and plantation” that inspired writers, statesmen, and colonial venturers of the early modern period.17 Maurice Abbot had taken on the labors of Hercules, through which he acquired a level of wealth and influence that few in London’s mercantile community could hope to rival. His initial voyage to Aleppo in 1588 provided him with an insider’s knowledge of the Mediterranean trade that vaulted him to the Levant Company chairmanship from 1607 to 1611. In 1600, a budding acumen for Asian commerce had led to a founding membership in the East India Company, where he would serve as a director until 1624, when his peers elected him company governor, a post he held until 1639.18 The commercial ventures launched by Abbot and other cosmopolitan capitalists reached northward into the Baltic, circled the Atlantic, lined the African coastline, ranged across the Mediterranean, and spread into the East Indies and beyond all the way to Japan. As a colonial entrepreneur, Abbot partnered with a faction of puritan noblemen and merchants looking to unite their trading interests in the Mediterranean and Indian Oceans with a commercial and plantation empire in the Americas. Joining forces with the militant Protestant earl of Warwick, Robert Rich, to secure profits and to thwart the imperial expansion of their most despised foreign enemy, Catholic Spain, Abbot’s faction helped found the Virginia Company (1606) and the Somers Island (or Bermuda) Company (1615). Abbot’s career offers an excellent case study of how the rise of the English Atlantic depended on previous experience with commerce and cash-crop plantation production in Africa and all the lands encompassing the Mediterranean Sea and Indian Ocean regions. But as wild as his dreams of riches grew, as high as his hopes for godly reform soared, and as far as his ships sailed into the world’s oceans, the London poor would always be with Maurice Abbot.19

IMAGE 1. This early nineteenth-century drawing of seventeenth-century housing in Moorfields, immediately adjacent to the northwest of Coleman Street Ward, gives us a vivid image of the conditions in which the London poor lived during the era of the English Revolution. Taken from J. T. Smith, Ancient Topography of London (London, 1815). Photo appears courtesy of The Newberry Library (folio F 02455 .798).

As a member of the St. Stephen’s parish vestry and as a common councilor and alderman for the City of London, Abbot administered poor relief in the parochial and municipal realms. He also helped draft ordinances against poor people like Walter Hill who, in violation of sixteenth-century antivagrancy laws, illegally decamped in London parishes. Importantly, Abbot paid the poor relief rates that he helped to set, a duty to the public good that we can be sure he and the more economically ambitious people from his class did not relish. While trying to keep the poor from starving, these self-styled guardians of the public weal also argued that the poor must not be allowed to starve the commonwealth of their labor. Their idle destitution, as the argument ran, equated economically with lost productivity and an upward trend in relief rates.20

Abbot’s public-spirited concern about the poor’s detrimental impact on the commonwealth found ample support in the literature of early modern English humanism. The commonwealth writers of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries who worked within this tradition had a highly class-conscious view of politics and confined what they alternately called “the people,” “the body politic,” or “civil society” to three orders: the nobility, the gentry, and the propertied men of the third order. In his much-studied book De Republica Anglorum, the Elizabethan scholar, diplomat, and statesman Thomas Smith defined the commonwealth as “a society or common doing of a multitude of free men collected together by common accord and covenants among themselves for the conservation of themselves as well in peace as in war.” Smith argued that the commonwealth (or state) existed primarily for two reasons; first, it must uphold the rule of law in civil society as the foundation of the people’s liberties; second, the public good required the state to create conditions conducive for free men to enrich themselves in ways that worked toward the “common profit” of the people, as the body politic would waste away without fresh infusions of economic lifeblood. For Smith and other political anatomists, increasing prosperity depended upon increasing economic innovation, which often came at the expense of the fourth order, the unpropertied commonality. In Smith’s concept of the commonwealth, propertyless commoners did not belong to civil society. They were not part of “the people,” who according to the fictional covenant struck by its constituent members existed to conserve themselves as well as their civil liberties, which flowed from their status as property owners. Smith, along with most other English humanists, classified the propertyless as subjects without rights, to be mastered by their social superiors. Without a stake in the state, they were bound to remain in profitable subjection to the propertied, to become, as the famous biblical phrase had it, “hewers of wood and drawers of water.”21

As Smith wrote, in the body politic “only the wealth of the lord is . . . sought for, not the profit of the slave or bondman.” The commonality were “bondsmen,” “slaves,” and tools to be used as “instruments” for the gain of their “lord(s),” the “multitude of men” in the body politic. Through the liberty allowed them in their covenant, free men possessed the sovereign power to expropriate the value of the commonality’s labor for their own increase and for the increase of the commonwealth at large. Smith saw a role for the state in this relationship and according to some historians even went so far as to craft a 1547 statute calling for the temporary enslavement of poor commoners. Regardless of the question of Smith’s authorship, the slave statute enjoyed a very short life, as his compatriots were unwilling to take the bold step of legally enslaving other English people, at least in England itself.

Perhaps the most important aspect of Smith’s thinking on the body politic and the public good is that it evolved mere political theory into a nascent political economy, a move that reveals how humanist principles regarding the commonwealth could translate easily into an ideology of colonization and empire-building. Smith and his contemporaries applied theory to practice in Ireland through the bloodshed of the Elizabethan conquests. Hundreds of thousands of Irish Catholics were killed in the Desmond (1569–73, 1579–83) and Tyrone Rebellions (1594–1603), through violence or planned famine, after resisting the “plantation” or colonization of Munster and Ulster. Few lofty-minded English humanists lost much sleep over the carnage; some such as Edmund Spenser infamously gloried in it. Less poetic than Spenser, Lord ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I

- Part II

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Index