- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Emile Durkheim on Institutional Analysis

About this book

Ranging from Durkheim's original lecture in sociology to an excerpt from the work incomplete at his death, these selections illuminate his multiple approaches to the crucial concept of social solidarity and the study of institutions as diverse as the law, morality, and the family. Durkheim's focus on social solidarity convinced him that sociology must investigate the way that individual behavior itself is the product of social forces. As these writings make clear, Durkheim pursued his powerful model of sociology through many fields, eventually synthesizing both materialist and idealist viewpoints into his functionalist model of society.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Emile Durkheim on Institutional Analysis by Emile Durkheim, Mark Traugott in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2013Print ISBN

9780226173719, 9780226173306eBook ISBN

9780226015361 Notes

A NOTE ON THE TRANSLATIONS

1. For a more discursive treatment of Durkheim’s use of this term, see Harry Alpert, Emile Durkheim and His Sociology (New York: Russell and Russell, 1961), pp. 163ff.; also, Terry N. Clark, “Emile Durkheim and the Institutionalization of Sociology in the French University System,” Archives Européenes de sociologie 9 (1968): 51ff. For Durkheim’s own discussion, see part 2 of “Sociology and the Social Sciences,” chapter 2, this volume.

2. For a discussion of the concept’s broader import, see Steven Lukes, Emile Durkheim, His Life and Work: A Historical and Critical Study (Harper and Row: New York, 1972), p. 4ff.

3. As Bohannan has pointed out, in either language the concept of “consciousness” involves a further ambiguity which is superimposed upon the difficulty of French-English translation, namely, that it may refer to any of the following: subjective awareness, the cognitive instruments whereby that awareness is achieved, or the objects to which that awareness is applied. See Paul Bohannan, “Conscience Collective and Culture,” in Emile Durkheim et al., Essays on Sociology and Philosophy, edited by Kurt H. Wolff (Harper and Row: New York, 1960), pp. 77–96.

INTRODUCTION

1. Harry Alpert, Emile Durkheim and His Sociology (New York: Russell and Russell, 1961).

2. Célestin Bouglé, “Quelques Souvenirs,” part of a hommage to Durkheim which appeared as Célestin Bouglé et al., “L’Oeuvre sociologique d’Emile Durkheim,” Europe: Revue mensuelle 22 (1930): 281–304. The play on words is lost in English. The French word chaire means at once rostrum, pulpit, and academic chair.

It is curious to note in this transference of religious sentiments rejected in childhood a distinct parallel to Weber, who declared himself to be “tonedeaf” in religious matters, while similarly devoting much of his academic work to their explication. In both cases, the proselytical impulse had been ruthlessly secularized. Bouglé continues the passage cited with this qualification: “But this preacher wanted above all to be an expositor; he hoped to convince on the strength of the facts.”

Georges Davy has also stressed the quality of Durkheim’s scholarship as vocation in “Emile Durkheim: L’Homme,” Revue de metaphysique et de morale 26 (1919): 181–98; 27 (1920): 71–112.

3. Steven Lukes, Emile Durkheim, His Life and Work: A Historical and Critical Study (New York: Harper and Row, 1972), p. 299. The committee’s decision was unanimous despite the fact that it included such arch-critics as Paul Genet, who had once solicitously warned Durkheim that the study of sociology led to madness. See Raymond Lenoir, “Lettre à R. M.,” in Célestin Bouglé et al., “L’Oeuvre sociologique d’Emile Durkheim,” p. 294.

4. Terry N. Clark, “Emile Durkheim and the Institutionalization of Sociology in the French University System,” Archives Européenes de sociologie 9 (1968): 54. A brief summary of the substance of this course on “Social Solidarity” will be found in the opening lecture of the course on “The Family” which Durkheim offered in the following year. See “Introduction to the Sociology of the Family,” chap. 5, this volume.

5. See “Opening Lecture,” chap. 1, this volume.

6. Ibid., p. 65. Robert K. Merton cites Durkheim as inspirator of his more explicit formulation of this doctrine, referring specifically to “Two Laws of Penal Evolution.” See Social Theory and Social Structure (Glencoe, Ill.: Free Press of Glencoe, 1968), p. 115ff.

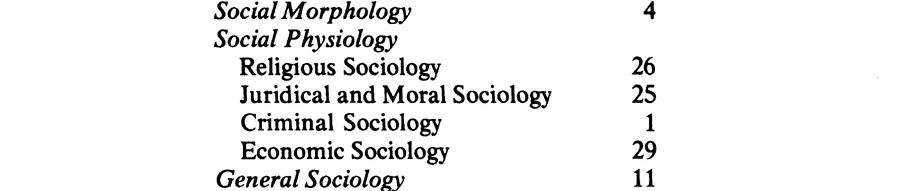

7. Of Durkheim’s three categories, social physiology is most fully elaborated into the following subdivisions: the sociology of religion, the sociology of morality, the sociology of law, economic sociology, linguistic sociology, and aesthetic sociology. Not surprisingly, these categories correspond almost exactly to those used to organize material in L’Année sociologique. A reworking of Terry Clark’s classification and coding of articles which appeared in the twelve volumes of that journal reveals the relative importance which Durkheim, as editor in chief, attributed to each:

See Terry N. Clark, “The Structure and Functions of a Research Institute: The Année sociologique,” Archives Européenes de sociologie 9 (1968): 76–77.

8. If, for present purposes, we emphasize the points of continuity between this article and Suicide itself, it should be noted that Durkheim introduced a number of significant changes in his reasoning in the later piece. These are discussed in detail in an excellent article by Philippe Besnard, “Durkheim et les femmes ou le Suicide inachevé,” Revue française de Sociologie 14 (1973): 27–61.

9. Having shown that the suicide rate in Catholic countries tended to be lower than that of Protestant countries, it remained for him to prove that the obvious conclusion was the correct one. It was possible and even plausible, after all, that the higher rate of suicide in Protestant countries resulted largely from an increased propensity to self-destruction on the part of a Catholic minority oppressed by life in a predominantly Protestant social environment. He looked, therefore, at second-order political divisions—for example, the constituent states of the German federation—and noted that the relation was reproduced in these more homogeneous units.

In point of fact, Selvin has shown that, while under specifiable conditions this technique can set limits upon the extent of ecological fallacy, these conditions are not met in the study of a low frequency phenomenon such as suicide. See Hanan C. Selvin, “Durkheim’s Suicide: Further Thoughts on a Methodological Classic,” in Emile Durkheim, edited by Robert A. Nisbet (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1965), pp. 113–36.

10. Robert N. Bellah sought to correct this misapprehension in “Durkheim and History,” in Emile Durkheim, edited by Robert A. Nisbet (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1965), pp. 153–76.

11. See, for example, “Introduction to the Sociology of the Family,” chap. 13, this volume.

12. “Sociology and Social Sciences,” p. 85, this volume.

13. Ibid., p. 261. In this statement, and also in his remarks concerning “social morphology,” Durkheim’s position bears a remarkable resemblance to that of the European school of historians known collectively as les Annalistes, from the title of the journal, Annales: Economies, societés, civilisations, which served as their focal point. See, for example, Femand Braudel, “History and the Social Sciences,” in Economy and Society in Early Modem Europe; Essays from Annales, edited by Peter Burke (New York: Harper and Row, 1972), pp. 11–42.

This convergence is no accident. Durkheim had a direct and significant impact on the thought of Henri Berr, the philosopher-historian around whom the founding circle of the Annales first gathered. A generation of “synthetic historians,” among them Lucien Fevre and Marc Bloch, were avid readers of L’Année sociologique. In this connection, see Lukes, Emile Durkheim, His Life and Work, p. 394 and Fernand Braudel, “Personal Testimony,” Journal of Modem History 44 (December, 1972): 448–67.

14. “Divorce by Mutual Consent,” pp. 247–48, this volume. Durkheim’s most concise statement of this principle is found in Moral Education (New York: The Free Press, 1973), p. 42. “The totality of moral regulations really forms about each person an imaginary wall, at the foot of which a multitude of human passions simply die without being able to go further. For the same reason—that they are contained—it becomes possible to satisfy them. But if at any point this barrier weakens, human forces—until now restrained—pour tumultously through the open breach; once loosed, they find no limits where they can or must stop. Unfortunately, they can only devote themselves to the pursuit of an end that always eludes them.”

15. See chap. 5, this volume.

16. See pp. 121–22, this volume. I do not wish to imply that Durkheim selected these terms directly in response to Tönnies, but only in response to the type of argument which Tönnies, like other German scholars before him, was advancing. It should be pointed out that in a reply to Durkheim’s review, Tönnies asserts that it was never his intention to make the argument Durkheim attributes to him. In any case, Durkheim’s terminology was already fixed in 1886 or 1887.

17. See “Course in Sociology: Opening Lecture,” especially part 1, below.

18. In his early descriptions of societies based on mechanical solidarity, Durkheim often relies on a rather indecorous simile which likens their aggregation of individual, familial, or clanic units to the arrangement of the segments of a worm (whence “segmental”). In The Division of Labor, he describes the consequences of this form of social organization in the following terms: “When society is made up of segments, whatever is produced in one of the segments has as little chance of re-echoing in the others as the segmental organization is strong. The cellular system naturally lends itself to the localization of social events and their consequences . . . ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Series Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- A Note on the Translations

- Introduction

- The Origins and Objectives of Sociology

- Reviews and Critical Analyses

- Law, Crime, and Social Health

- The Science of Morality

- Sociology of the Family

- Notes

- Index