- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Nutrition in the Middle and Later Years

About this book

Nutrition in the Middle and Later Years focuses on the behavioral and biochemical aspects of eating geared to the population aged 45 or older. The selection first offers information on nutrition and lifestyle and nutritional requirements and the appropriate use of supplements. Topics include proteins, carbohydrates, fat soluble vitamins, minerals, status and aging, social isolation, and loss of income or reliance on fixed income. The text then elaborates on animal models in aging research and evaluation and treatment of obesity. The manuscript takes a look at alcoholism and nutritional factors in cardiovascular disease. Discussions focus on diet and atherosclerosis, general aspects of carbohydrate, lipid, and protein metabolism in the alcoholic, and management of elderly alcoholic. The text also examines the relationship of nutrition and cancer, nutrition and gastrointestinal tract disorders, and neurological manifestations of nutritional deficiencies. The selection is highly recommended for nutritionists and readers wanting to conduct studies on nutrition during the middle and later years.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Nutrition in the Middle and Later Years by Elaine B. Feldman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Alternative & Complementary Medicine. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Nutrition and Lifestyle

Sandra J. Edwards

Publisher Summary

The social aspects of food and eating relate to the nutritional status of the middle aged and elderly. This chapter discusses both the sociologic and the psychologic aspects of the middle-aged and elderly lifestyles that relate to nutritional status. Important issues that interfere with the pleasurable aspects of eating are the status of aging, social isolation, loss of mobility, the effects of decreased or fixed income, food beliefs and practices, and attitudes toward illness and death. Several factors relate to eating behavior: marital status, household composition, and mealtime companionship. Aging individuals vary in their choice of social relationship; some become isolates, some desolates. Social changes may be reflected in eating patterns. Men tend to eat more meals away from home; eating becomes more of a social event for them. Women spend less on groceries and the amount goes down proportionately as the income rises.

The social aspects of food and eating relate to the nutritional status of the middle aged and elderly. Food and eating patterns themselves are sociological variables. For example: food is seen as a form of currency; eating is a pleasurable recreational activity; food and eating are sources of aesthetic and creative satisfaction, supernatural, religious or even magical significance. Food is related to security. Food and eating are cultural factors; they symbolize interpersonal acceptance, friendliness, sociability, and warmth. Eating is seen as a duty, a virtue, a gustatory pleasure.1 Adults who build their social life around the pleasures of food and drink are approaching the subject of nutrition from a social rather than physiologic point of view. This chapter will address that approach by considering both the sociologic and the psychologic aspects of the middle-aged and elderly lifestyles that relate to nutritional status. Important issues that interfere with the pleasurable aspects of eating are the status of aging, social isolation, loss of mobility, the effects of decreased or fixed income, food beliefs and practices, and attitudes toward illness and death. These issues will be discussed.

Most of the available literature deals with the elderly and only recently has research on the middle aged become notable. Middle age begins at the midlife transition, which begins around 40 according to Levinson,2 between 45 and 64 in some United States census reports, when children leave home, or whenever perceived by the individual.3 Old age generally is defined as 65 and over, but social milestones such as retirement and eligibility for social security also serve as demarcations of elderly status. While middle age may represent the prime of life for many persons, for purposes of this paper it will be viewed (as in real life) as the preamble of old age.

Demographic information on aging gives dramatic indication of changes in the United States population. The average life span of a United States resident has increased 20 years in the past century primarily due to decreases in mortality in infancy and early childhood. The median age has increased from 27.9 years in 1970 to 29.0 in 1976.4

In 1977 a male baby was expected to live to 68.7 years and a female baby to 76.5 years. The Bureau of the Census predicts that by the year 2050 the life expectancy at birth of a male will be 71.8 years and of a female 81 years. One interesting note, however, is that the longevity of men in affluent classes has changed little since the 18th century. For example, George Washington lived to age 67, John Adams to 91, Thomas Jefferson to 83, James Madison to 85, Monroe to 73, John Quincy Adams to 81, and Andrew Jackson to 78 compared with a general life expectancy in those days of about 35 for men.5

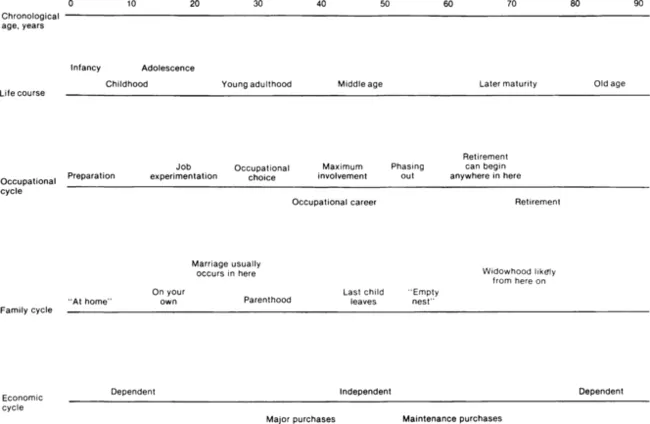

The continuous increase in the age of the United States population requires more consideration of the lifestyle of the aging. Many changes in social roles take place. Figure 1-1 gives a general overview of the relationship between lifecourse and other aspects of the life cycle including occupational cycle, family cycle, and economic cycle. The social role that an individual plays in the organization of society can mean one of three things: 1) what is expected of a person in a given position, 2) what most people do in a given position, or, 3) what a particular person does in a given position. There is often a gap between the ideal, the expected and the actual behavior.6 This chapter will deal with the actual behavior of the older population, and the social and psychological aspects of this lifestyle that influence nutritional status.

Figure 1-1 Relationships among age, life cycle, occupational cycle, and family cycle. (These relationships fluctuate widely for specific individuals and for various social categories such as ethnic groups or social classes.) Reprinted by permission from: Atchely RC: The Social Forces in Later Life, ed 3. Belmont, CA, Wadsworth, Inc, 1980.

Status and Aging

Since American society values high attainment, wealth, and youth, age per se does not necessarily engender prestige, status, or influence. More often, it is socioeconomic status rather than age that brings these benefits. In other societies—the Chinese society, for example, individuals are given more respect and deference as they age. In Western societies, aging leads to diminished activity, because of actual physical limitations, aging individuals perceive themselves differently, or the people around them perceive them as old.7

A press toward conforming to age norms also exists. The young are often less constrained by norms because these norms include divesting themselves of parental expectations, but older people invest more in acting in a desirable or appropriate fashion.8 Adjustments to role changes, which result from loss of status and acceptance of age-related norms, influence self-esteem.9

Since food is a social activity, any feelings of loss of status and resulting loss of self-esteem may be reflected in food and eating patterns. Since food is power and security, it may be a symbol of prestige and status, an overture of hospitality and friendship, and a positive outlet for emotions.10 If food is used in this way, then good nutritional practices may be maintained. However, if food and eating become an outlet for negative emotions, such as feelings of depression or anxiety, nutritional status may deteriorate.

Studies indicate that dissatisfaction with social role or with life in general may influence appetite. Harrill, Erbes, and Schwartz11 found that the women nursing home residents who were most dissatisfied with their lives had lower than normal calorie nutrient intake for all nutrients except ascorbic acid. A study by Rankin12 described observations by the staff of a geriatric living facility of the positive effect of residents coming to a community dining room for meals. The meal became the high point of the day. It stimulated socialization activities, less meal skipping, and reduced plate waste. This change probably resulted from increasing the sense of community (see the next section), but also reflects an increase in the level of self-esteem among the residents of this facility. Institutions often depersonalize individuals by not allowing free access to food.9 Yet, institutions are not the only source of low morale among this population. For example, Learner and Kivett13 describe a relationship between low morale and frequent diet problems in a rural population (418 subjects, age 65 and older).

The general feelings of powerlessness, inability to make decisions, frustrations resulting from submission to decisions by others, all contribute to a sense of dependence and loss of status and can influence eating patterns. Howell and Loeb14 also describe age-appropriate concerns of changing body image that may influence diet, such as preoccupations with digestion, constipation, and “iron-poor” blood. There is, however, a positive side. Lewis Harris15 reports that the vast majority of the aged are satisfied with life, happy, and live meaningful existences, which is contrary to the usual stereotype of the older person in American society. Morale is based on comparisons with peers and one’s own earlier self.9

Social Isolation

Data are inconsistent on the impact of companionship on nutritional status. One of the features most salient in an elderly person’s life is the loss of significant others—the loss of relatives, friends, neighbors through death or change of residence.

Several factors relate to eating behavior: marital status, household composition, and mealtime companionship.13 Aging individuals vary in their choice of social relationship; some become isolates, some desolates.10,16 Isolates are people who live alone by choice; that is, they have lost spouses but choose to remain independent. More women than men tend to be isolates, because women more often outlive men; women tend to marry men older than themselves who, therefore, die before they do; older women often have fewer opportunities to remarry; and women are more likely to b...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Copyright

- Table of Contents

- CONTRIBUTORS

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- PREFACE

- FOREWORD

- Chapter 1: Nutrition and Lifestyle

- Chapter 2: Nutritional Requirements and the Appropriate Use of Supplements

- Chapter 3: Animal Models in Aging Research

- Chapter 4: Evaluation and Treatment of Obesity

- Chapter 5: The Elderly Alcoholic

- Chapter 6: Nutritional Factors in Cardiovascular Disease

- Chapter 7: Nutrition and Cancer

- Chapter 8: Nutrition and Gastrointestinal Tract Disorders

- Chapter 9: Nutritional Therapy of Renal Failure

- Chapter 10: Neurological Manifestations of Nutritional Deficiencies

- Chapter 11: The Histological Heterogeneity of Osteopenia in the Middle-Aged and Elderly Patient

- Chapter 12: Nutrition-Related Oral Problems

- Chapter 13: Enteral and Parenteral Feeding

- Chapter 14: Quackery and Fad Diets

- Chapter 15: Dietary Compliance

- Chapter 16: Federal Nutritional Support of the Elderly

- INDEX