- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Ship Construction

About this book

Ship Construction, Seventh Edition, offers guidance for ship design and shipbuilding from start to finish. It provides an overview of current shipyard techniques, safety in shipyard practice, materials and strengths, welding and cutting, and ship structure, along with computer-aided design and manufacture, international regulations for ship types, new materials, and fabrication technologies. Comprised of seven sections divided into 32 chapters, the book introduces the reader to shipbuilding, including the basic design of a ship, ship dimensions and category, and development of ship types. It then turns to a discussion of rules and regulations governing ship strength and structural integrity, testing of materials used in ship construction, and welding practices and weld testing. Developments in the layout of a shipyard are also considered, along with development of the initial structural and arrangement design into information usable by production; the processes involved in the preparation and machining of a plate or section; and how a ship structure is assembled. A number of websites containing further information, drawings, and photographs, as well as regulations that apply to ships and their construction, are listed at the end of most chapters. This text is an invaluable resource for students of marine sciences and technology, practicing marine engineers and naval architects, and professionals from other disciplines ranging from law to insurance, accounting, and logistics.- Covers the complete ship construction process including the development of ship types, materials and strengths, welding and cutting and ship structure, with numerous clear line diagrams included for ease of understanding- Includes the latest developments in technology and shipyard methods, including a new chapter on computer-aided design and manufacture- Essential for students and professionals, particularly those working in shipyards, supervising ship construction, conversion and maintenance

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part 1

Introduction to Shipbuilding

1

Basic design of the ship

Chapter Outline

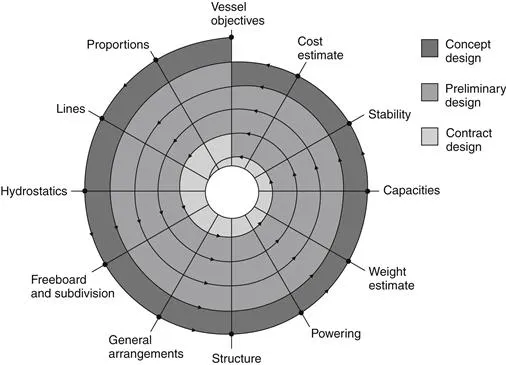

Preparation of the design

Information provided by design

Many vessels are required to make passages through various canals and straits and pass under bridges within enclosed waters, and this will place a limitation on their dimensions. For example, locks in the Panama Canal and St Lawrence Seaway limit length, breadth, and draft. At the time of writing, the Malacca Straits main shipping channel is about 25 meters deep and the Suez Canal could accommodate ships with a beam of up to 75 meters and maximum draft of 16 metres. A maximum air draft on container ships of around 40 meters is very close to clear the heights of the Gerard Desmond Bridge, Long Beach, California and Bayonne Bridge, New York. Newer bridges over the Suez Canal at 65 meters and over the Bosporus at 62 meters provide greater clearance.

A service speed is the average speed at sea with normal service power and loading under average weather conditions. A trial speed is the average speed obtained using the maximum power over a measured course in calm weather with a clean hull and specified load condition. This speed may be a knot or so more than the service speed.

Unless a hull form similar to that of a known performance vessel is used, a computer-generated hull form and its predicted propulsive performance can be determined. The propulsive performance can be confirmed by subsequent tank testing of a model hull, which may suggest further beneficial modifications.

The owner may specify the type and make of main propulsion machinery installation with which their operating personnel are familiar.

Purchase of a new vessel

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- copyright

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Part 1 Introduction to Shipbuilding

- Part 2 Materials and Strength of Ships

- Part 3 Welding and Cutting

- Part 4 Shipyard Practice

- Part 5 Ship Structure

- Part 6 Outfit

- Part 7 International Regulations

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app