- 276 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

Ocular transporters and receptors contains detailed descriptions of major transporters and receptors expressed in the eye, with special emphasis on their role in drug delivery. The complex anatomy and the existence of multiple barriers in the eye pose a considerable challenge to successful drug delivery to the eye. Hence ocular transporters and receptors are important targets for drug delivery. A significant advancement has been made in the field of ocular transport research and their role in drug delivery. In this book the cutting edge research being carried out in this field is compiled and summarized. The book focuses on key areas, including the anatomy and physiology of the eye, biology of ocular transporters and receptors, techniques in characterization of transporters and receptors, transporters and receptors in the anterior and posterior segment in the eye, the role of ocular transporters and receptors in drug delivery, and transporter-metabolism interplay in the eye.- Highly focused on ocular transporters- Most up-to-date research compilation- Detailed description of role of transporters and receptors in ocular drug discovery and delivery

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

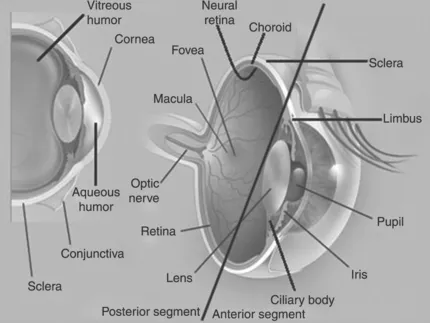

Eye: anatomy, physiology and barriers to drug delivery

Abstract:

1.1 Introduction

1.2 Anatomy and physiology of the eye

1.2.1 Anterior segment

Cornea

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- List of figures and tables

- About the authors

- Chapter 1: Eye: anatomy, physiology and barriers to drug delivery

- Chapter 2: Biology of ocular transporters: efflux and influx transporters in the eye

- Chapter 3: Characterization of ocular transporters

- Chapter 4: Transporters and receptors in the anterior segment of the eye

- Chapter 5: Transporters and receptors in the posterior segment of the eye

- Chapter 6: Transporters in drug discovery and delivery: a new paradigm in ocular drug design

- Chapter 7: Transporter–metabolism interplay in the eye

- Index