- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Electronic and algorithmic trading has become part of a mainstream response to buy-side traders' need to move large blocks of shares with minimum market impact in today's complex institutional trading environment. This book illustrates an overview of key providers in the marketplace. With electronic trading platforms becoming increasingly sophisticated, more cost effective measures handling larger order flow is becoming a reality. The higher reliance on electronic trading has had profound implications for vendors and users of information and trading products. Broker dealers providing solutions through their products are facing changes in their business models such as: relationships with sellside customers, relationships with buyside customers, the importance of broker neutrality, the role of direct market access, and the relationship with prime brokers.

Electronic and Algorithmic Trading Technology: The Complete Guide is the ultimate guide to managers, institutional investors, broker dealers, and software vendors to better understand innovative technologies that can cut transaction costs, eliminate human error, boost trading efficiency and supplement productivity. As economic and regulatory pressures are driving financial institutions to seek efficiency gains by improving the quality of software systems, firms are devoting increasing amounts of financial and human capital to maintaining their competitive edge. This book is written to aid the management and development of IT systems for financial institutions. Although the book focuses on the securities industry, its solution framework can be applied to satisfy complex automation requirements within very different sectors of financial services – from payments and cash management, to insurance and securities. Electronic and Algorithmic Trading: The Complete Guide is geared toward all levels of technology, investment management and the financial service professionals responsible for developing and implementing cutting-edge technology. It outlines a complete framework for successfully building a software system that provides the functionalities required by the business model. It is revolutionary as the first guide to cover everything from the technologies to how to evaluate tools to best practices for IT management.

- First book to address the hot topic of how systems can be designed to maximize the benefits of program and algorithmic trading

- Outlines a complete framework for developing a software system that meets the needs of the firm's business model

- Provides a robust system for making the build vs. buy decision based on business requirements

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1 Overview of Electronic and Algorithmic Trading

1.1 Overview

Electronic and algorithmic trading has become a significantly larger focus for financial institutions, securities regulators, and different exchanges. Market developments along with tougher regulations have made equity trading more complicated and less profitable. Automation and new technologies have changed the trading game dramatically in the past five years or so. The speed of financial information is outpacing anyone’s forecast. Higher networking speeds through financial engineering are altering the way traders and market participants address the demand for lower commissions and enabling the creation of automated model-based trading. The increase in competition for lower transaction costs has been forcing firms to invest significantly in their trading and processing infrastructure. The proliferation of electronic and algorithmic trading has been staggering on Wall Street. A broker can no longer fulfill order flow without using some method of electronic execution. The traditional clerks running across the trading floor with order slips and men in pits negotiating bid prices may soon be replaced by the sound of traders typing in their parameters onto their broker screens to facilitate order flow using programs and algorithms. In the past, there were limited opportunities to apply technology to the trading process or interact directly with exchanges and market participants. This has all changed with the introduction of programs, direct market access, and algorithmic trading. Although automated trade flow can carry connotations of computerized trading taking over without human supervision, the actual decisions to buy and sell are made by people, not computers. Humans make the final trading decisions and the parameters behind implementing them, but computers may calculate algorithms that route the order flow efficiently and in many cases, computers help the breakdown of trades to each individual stock within the program.

1.2 The Emergence of Electronic Trading Networks

Algorithmic trading has become another method for large brokerage firms to grasp an advantage over their competitors for lower-cost executions; however, smaller players such as agency brokers also see algorithms as a way to level the playing field and infringe on the bigger bulge-bracket firms. Algorithmic trading originated on proprietary trading desks of investment banking firms. It began to expand executing client orders because of new markets and the need to remain in line with new players in the brokerage industry. This has created a more competitive environment for traditional dealers with services such as direct market access through the Internet. According to Manny Santayana, managing director at Credit Suisse’s Advanced Execution Services Group (AES), “Algorithmic trading has created a level playing field which ultimately benefits shareholders with smarter, more efficient, and cheaper execution.” NASDAQ and other electronic exchanges have threatened the traditional model of the New York Stock Exchange with their phone-based order flow, and its utilization of floor brokers.

In 2001, the Securities and Exchange Commission imposed decimalization. This mandate forced market makers and buy-side institutions to switch from valuing stocks in traditional sixteenths ($.0625) to valuing them in penny spreads ($.01), which increased price points from 6 for every dollar to 100. Trading margins have been significantly reduced by 84% as a result. The SEC mandate has had unintentional impacts. The idea was to lower the cost of transactions for smaller investors and individuals, but it inadvertently reduced trading margins for big dealers to the point where many left the industry or reduced their market presence. The remaining participants were forced to quickly adopt electronic order management systems and more efficient routing technology. The emergence of electronic trading networks and new sophisticated trading systems further diminished profitability through lower trading costs. Decimalization and the availability of FIX are the two drivers that have promoted algorithmic trading along with the reduction of soft dollar commissions buy-side firms are willing to pay. The Financial Information Exchange (FIX) Protocol is a series of messaging specifications for electronic communication protocol developed for international real-time exchange of securities transactions in the finance markets. It has been developed through the collaboration of banks, broker-dealers, exchanges, industry utilities institutional investors, and information technology providers from around the world. A company called FIX Protocol, Ltd., established for this purpose, maintains and owns the specification, while keeping it in the public domain. FIX is open and free, but it is not software. FIX is a specification around which software developers can create commercial or open-source software, as they see fit. As the market’s leading trade communications protocol, FIX is integral to many order management and trading systems. Eric Goldberg, CEO of Portware, a global securities industry’s leading developer of broker-neutral trading software states, “FIX as a standardized protocol has made it possible for independent software vendors to provide destination-neutral systems for electronic trading. As the proliferation of FIX continues to increase the use of electronic trading worldwide, algorithmic trading won’t be far behind. As use of FIX grows, so will the use of algorithmic trading.”1 FIX was first developed at Salomon Brothers in 1992 to facilitate equity trading between Fidelity Investments.2 It has become the messaging standard for pre-trade and trade communication globally. This communication is done through electronic communication networks (ECNs), which use Web-based platforms. This collects limit and market orders and matches them or displays them on an Internet-based order book. The largest ECN, Instinet, was estimated to represent 12% of the trading volume on NASDAQ in February 2002, while Island, another Web-based transparent limit order book, amounted to 9.6%, RediBook 6.5%, and Archipelago 10.5%.3 ECNs compete with traditional NASDAQ market makers, but do not take on proprietary positions. They simply handle and display customer orders. They also cannot conduct trades away from the current best market price and must allocate orders according to price priority. Decimal pricing decreased the volume of stocks that had been available at prices that were fractions of a dollar into smaller pools available at prices that differ by just a penny. Algorithmic trading has become a solution for the problem of smaller spreads and market fragmentation. Algorithmic programs have the ability to slice parent orders, which are large blocks of shares, efficiently, ensuring that each tiny order or child order gets the best price. The emergence of new niche players in the algorithmic market has created variety among market makers but does not seem to pose a serious threat to bigger Wall Street broker-dealers. There will always be niche players, but noncompetitive market makers are likely to step aside, while the better ones will form alliances or be acquired by larger participants. Algorithmic trading may not replace traders; it is only as effective as the traders who design and use it. However, traders who learn to use algorithmic programs more effectively will theoretically replace a large number of traders who do not understand how to use the new technologically advanced resources to their advantage. There are currently many execution choices available to traders. Some require greater human intervention and complexity; others can be automated and less complex. Each option has its drawbacks depending on the nature of a particular trade. Algorithmic trading currently focuses on equity markets but frontiers such as small cap stock have not been tapped yet. In the future, these could include fixed income, futures, options, and foreign exchange. Whether or not algorithms can work effectively with illiquid securities such as small cap stock and many fixed income instruments remains to be seen. Algorithms, which were traditionally associated with one particular asset class, namely equities, are diversifying into other markets that are rapidly evolving toward electronic trading. Participants in other asset classes such as derivatives tend to be comfortable and savvy with technology to begin with, so moving to a more systematic algorithmic approach to some of these classes may not seem as radical. Algorithmic trading may soon find a place in futures, options, and foreign exchange. Fixed-income instruments are most likely to be the last asset class to move into algorithmic trading or rely on electronic communication networks to facilitate order flow. However, this technologically advanced strategy is offered in small quantities or to very liquid markets in fixed income such as U.S. Treasuries and other government securities.

1.3 The Participants

Sell-side brokerage firms originally developed algorithmic programs to execute transactions on behalf of their firm’s proprietary accounts. They were originally designed in-house, but outside vendors provide direct market access/order management systems for customer trading and provide a centralized order processing and clearing system. Sell-side players constantly innovate and customize their algorithms to be more competitive than their peers to offer more efficient order flow while further lowering transaction costs. They also offer their in-house algorithms to clients and smaller firms. Algorithmic strategies offered by sell-side firms to clients are often customized, with customers having the ability to create their own stylized versions. The increase in options for customized algorithms can better serve portfolio managers’ trading styles. Customized algorithms for buy-side clients can be appealing, but the wealth of options can complicate the client’s ability to make the most appropriate selection, and measuring performance between different algorithms can become a daunting task. A proposed algorithmic trade should give you a visual representation of the impact cost and volatility. Post-trade data reports can theoretically guide clients with quickly available data regarding how efficiently trades have been executed. Measuring performance is crucial but often gets difficult and complex with customized order flow.

Big brokerage firms are not the only participants offering algorithm strategies; agency brokers and other vendors are providing these services to clients (see Exhibit 1.1). Algorithms are increasingly becoming more complex with average execution size decreasing to a few hundred shares from several thousand five years ago. Big brokerage firms are losing trading commissions by offering algorithms to fund managers, but they have no choice because of intense competition to lower execution costs. The role of the sales trader at brokerage firms will also change. Sell-side traders will increasingly offer consulting services advising how clients should get the best execution depending on market conditions as opposed to their traditional role of providing the execution service themselves.

Exhibit 1.1 Source: Algorithmic Trading Hype or Reality, Aite Group 2005.

The customers who use algorithmic strategies are institutions such as mutual funds, pension funds, and private money managers called hedge funds. Hedge funds are private investment firms that have fairly unrestricted investment criteria. Unlike most mutual funds, hedge funds can invest in a wide selection of investments, as well as sell-short investment products. Advances in technology and regulation-driven changes in market structure have transformed the kinds of trading options available to ensure the best execution for institutional investors. After years sitting on the sidelines, these institutions, also known as the buy side, have finally entered the algorithmic trading game. The latest advance in electronic tools allows users of algorithmic trading strategies to predefine rules regarding how an order should be executed. Traders must calibrate the algorithms to suit their portfolio strategy. Buy-side firms such as Putnam Investments, the mutual fund giant that manages about $200 billion in assets, have used algorithms for the past couple of years. Approximately 5% of trades placed by money managers are currently executed with an in-house algorithm. This number is expected to increase to over 20% in the next couple of years. Algorithms are a step up from the more familiar program trading and pose dangers for inexperienced hedge and mutual fund traders. Algorithmic trading strategies can become predictable and display patterns. Regulators are aware of the potential problems in algorithmic trading. The NASD is currently cooperating with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), collecting documents and interviewing traders to learn more about the programs and their potential for abuse. Many buy-side institutions are building their own algorithms or are considering it in the near future.

Algorithmic trading usually increases message traffic on the exchanges by adjusting and readjusting orders. According to information provided by NASDAQ, message traffic has doubled in the last year and is up more than threefold since the beginning of 2004 to the end of 2005. A significant part of electronic trading is being carried out via an algorithm or program. Program trading currently accounts for more than 50% of trading on the New York Stock Exchange. This figure is bound to climb as more fund managers trade stocks in baskets because trading algorithms allow them to do so with greater ease.

1.4 The Impact of Decimalization

The NASDAQ Stock Market implemented decimalization in 2001. The change was intended to lower trading costs and make stock prices easier to understand for investors and was proposed by Congress in the Common Cents Pricing Act of 1997, which was later mandated by the Securities and Exchange Commission Order 34-42360 in January2000. Since 1997, U.S. markets were the only major stock markets in the world that utilized fraction prices and quotes. The introduction of decimalization was executed in three phases in order to respect either capacity or market quality considerations and cause minimal disruption in financial markets:

- Phase I On March 12, 2001, 14 non–NASDAQ 100 securities were decimalized.

- Phase II On March 26, 2001, another 197 securities representing 174 companies were decimalized.

- Phase III All remaining NASDAQ securities were converted to penny increments on April 9, 2001.

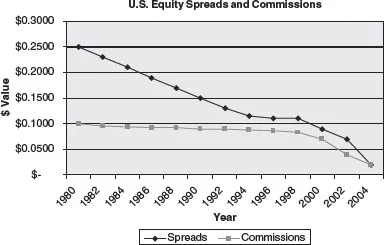

Decimalization lowered trading costs particularly for retail investors by allowing tighter bid-ask spreads (see Exhibit 1.2); however, this also resulted in significantly reduced profit for market makers, and the exit of many of those participants. According to the NASDAQ decimalization report to the SEC, for most actively traded securities, the quoted spread fell from 6.6 cents to 1.9 cents when penny increments were introduced. Among the major concerns with trading smaller tick size is the capacity impact on message traffic. The two general classes of messages that were mainly considered include quote updates disseminated by the various market centers, and the Last Sale trade report disseminated by NASDAQ.

Exhibit 1.2 Source: Institutional Equity Trading in America, TABB Group, June 2005.

With the introduction of decimalization, large institutional orders will most likely ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- About the Author

- Series Preface

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Overview of Electronic and Algorithmic Trading

- Chapter 2: Automating Trade and Order Flow

- Chapter 3: The Growth of Program and Algorithmic Trading

- Chapter 4: Alternative Execution Venues

- Chapter 5: Algorithmic Strategies

- Chapter 6: Algorithmic Feasibility and Limitations

- Chapter 7: Electronic Trading Networks

- Chapter 8: Effective Data Management

- Chapter 9: Minimizing Execution Costs

- Chapter 10: Transaction Cost Research

- Chapter 11: Electronic and Algorithmic Trading for Different Asset Classes

- Chapter 12: Regulation NMS and Other Regulatory Reporting

- Chapter 13: Build vs. Buy

- Chapter 14: Trading Technology and Prime Brokerage

- Chapter 15: Profiling the Leading Vendors

- Appendix: The Implementation of Trading Systems

- Glossary of Terms

- Index

- Instructions for online access

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Electronic and Algorithmic Trading Technology by Kendall Kim in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Computer Science & Investments & Securities. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.