![]()

Chapter 1

History of Rabies Research

Alan C. Jackson, Departments of Internal Medicine (Neurology) and Medical Microbiology University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba R3A 1R9, Canada

1 Ancient Greek and Roman times

The ancient Greeks coined the word lyssa for rabies in dogs, apparently from the root lud, meaning “violent.” The writings of Democritus, Aristotle, Hippocrates, and Celsus described the clinical features of rabies (Fleming, 1872). For example, Aristotle wrote “the disease is fatal to the dog itself and to any animal that it may bite, man excepted,” but it is unclear whether or not he thought humans were susceptible to rabies (Wilkinson, 1977). Fracastoro (1930) has suggested that Aristotle was merely emphasizing that humans may not develop disease after a bite. Hippocrates probably refers to rabies when he wrote that persons in a frenzy drink very little, are disturbed and frightened, tremble at the least noise, or are seized with convulsions (Fleming, 1872). In 100 AD, the physician Celsus described human rabies and used the term hydrophobia (hudrophobian), which is derived from Greek words meaning “fear of water.” Celsus recognized that the saliva of the biting animal contained the poisonous agent: “every bite has mostly some venom” (aiitem omnis morsus hahetfere quoddam virus), and he recommended the practice of using caustics, burning, cupping, and also sucking the wounds due to rabid dog bites (Fleming, 1872). Hence, rabies was prevalent and reasonably well understood in these ancient times.

Thomsen & Blaisdell (1994) have postulated that these early ideas about rabies may have come from writings about Cerberus, the multi-headed dog of Hades. A variety of literary sources in the period 800–700 BC, including Homer’s Iliad, contained passages describing this creature, whose task it was to guard the underworld. Homer is also thought to refer to rabies when he refers to the “dog-star, or Orion’s dog, as exerting a malignant influence upon the health of mankind” (Fleming, 1872). The myth likely originated in oral folklore. Cerberus manifested mad behavior and emitted poisonous substances from his jaws. In this myth, Cerberus has features of rabies, and the myth may have influenced classical beliefs about rabies (Thomsen & Blaisdell, 1994).

2 Girolamo Fracastoro

Girolamo Fracastoro (1478–1553) was an Italian physician who proposed a scientific germ theory of disease (theory of contagion) more than 300 years before the experimental studies of Robert Koch and Louis Pasteur laid the foundations of modern microbiology. In 1546, Fracastoro wrote: “Since, then, this contagion is not communicated by fomes, and is not produced in the skin by simple contact, but requires laceration of the skin, we must suppose that its germs are not very viscous, and that they are perhaps too thick to be able to establish themselves in pores” (Fracastoro, 1930). Although the nature of viruses was not understood until centuries later, Francastoro had great insight into the nature of the viral agent causing rabies. Francastoro also described clinical rabies in humans.

3 John Morgagni

In 1769, the pathologist John Morgagni (1735–1789), who has been described as the father of pathological anatomy, speculated that rabies “virus does not seem to be carried through the veins, but by the nerves, up to their origins” (Morgagni, 1960). He apparently concluded this because he noted that the early symptom of paresthesias in rabies occurred in the area of the original wound (Johnson, 1965)

4 Earliest Pathogenesis Studies

In 1804, Georg Gottfried Zinke (1771–1813) published a volume that was designed to prove that the infective agent of rabies was transmitted in infected saliva (Zinke, 1804). This work contained the first planned experimental studies on transmission of a viral disease. He took saliva from a rabid dog and painted it with a small brush into incisions he had made in healthy animals, including other dogs, cats, and rabbits, and the animals subsequently developed rabies (Wilkinson, 1977). These experiments proved that rabies was an infectious disease. A few years earlier, in 1793, John Hunter (1754–1809) suggested evaluating the transmissibility of rabies between species and indicated that transmission by incision and transfer of infected saliva on the point of a lancet should be feasible (Hunter, 1793). However, it is unclear if Zinke had read this article and whether or not it provided the inspiration for his experiments (Wilkinson, 1977). In 1821, the French neurophysiologist François Magendie (1783–1855) reported the transmission of rabies to a dog by inoculation of saliva from a human case of rabies (Magendie, 1821), but there was no indication that he was familiar with the previous writings of either John Hunter or Georg Zinke (Wilkinson, 1977).

5 Louis Pasteur and Rabies Vaccination

In 1879, Pierre-Victor Galtier (1846–1908), who was a professor at a veterinary school in Lyon, France, used rabbits in his rabies experiments, which was technically much less difficult and less dangerous than experiments using dogs and cats, and he noted the paralytic and convulsive features of the disease in this species (Galtier, 1879; Wilkinson, 1977). Experimental transmission from dogs to rabbits was also associated with a marked reduction in the incubation period of rabies to an average of 18 days in rabbits (versus about a month in dogs), in addition to the advantages of being relatively cheap, easy to handle, and easy to keep (Geison, 1995). Shortly afterwards, the experimental model in rabbits was taken up by Pasteur.

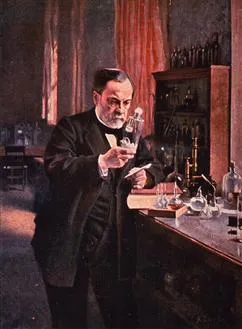

Louis Pasteur (1822–1895) experimentally transmitted rabies virus by inoculating central nervous system (CNS) material of rabid animals into the brains of other animals (Figure 1.1). In 1881, Pasteur published his first paper on rabies (Pasteur, Chamberland, Roux, & Thuillier, 1881). A technique was developed to transmit the disease from one animal to another. Brain tissue was extracted from a rabid dog under sterile conditions and then inoculated subdurally onto the surface of the brain of a healthy dog via trephination, which reduced the incubation period from a month in dogs with transmission from bites to less than three weeks. Subsequently, Pasteur noted progressive shortening of the incubation period to a limit of 6 to 7 days, in which the virus and the incubation period became “fixed” (Pasteur, 1885), and the term “fixed” has persisted and has become standard terminology for laboratory strains that have been generated in this manner. The fixed virus was found to be more neurovirulent than the street (wild-type) virus, and it had a shorter and more reproducible incubation period. Pasteur also observed that sequential passage in the CNS led to attenuation after peripheral inoculation (Pasteur, Chamberland, & Roux, 1884). In 1885, Pasteur successfully immunized the first patient, Joseph Meister, with his rabies vaccine.

Figure 1.1 Portrait of Louis Pasteur working in his laboratory. From Images from the History of Medicine (National Library of Medicine) (http://ihm.nlm.nih.gov/images/B30055).

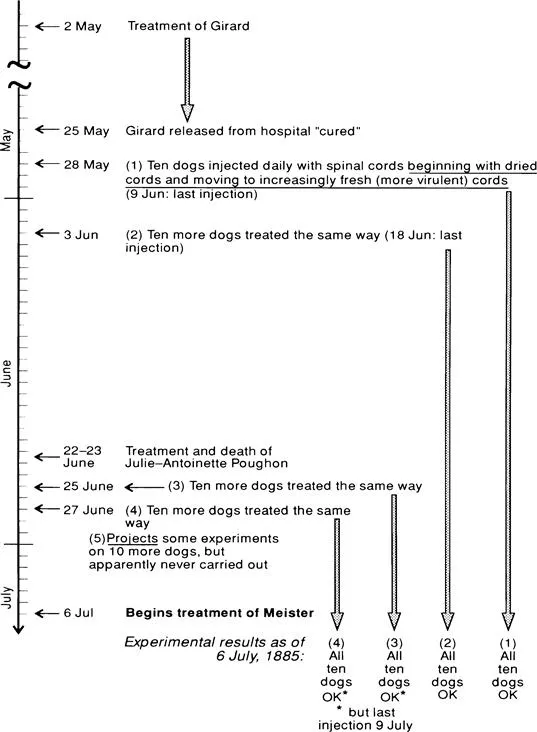

Gerald Geison published information acquired from Pasteur’s private laboratory notebooks, which did not become available until after the death of Pasteur’s grandson in 1971. There was no printed catalogue of the collection until 1985 (Geison, 1995). Pasteur had actually treated two patients with suspected rabies with his rabies vaccine prior to Meister (Figure 1.2), which never appeared in any of his publications. The first case was Girard, a 61-year-old Parisian man who had been bitten by a dog in March and was admitted to the Necker Hospital with a suspicion of rabies (Geison, 1995). On May 2, 1885, Girard was injected with a dose of Pasteur’s vaccine prepared from desiccated rabbit spinal cords, but no further doses were given because of concerns by hospital authorities and the absence of Girard’s attending physician. Girard deteriorated through May 6th, then improved and was discharged as cured on May 25th without further follow-up. In retrospect, it seems clear that Girard did not actually have rabies. The second case was Julie-Antoinette Poughon, an 11-year-old girl who had been bitten on the lip by her puppy in May and had clinical features of rabies and was admitted to the Hospital of St. Denis (Geison, 1995). She was given two doses of Pasteur’s vaccine beginning on June 22, 1885, and she died on June 23rd. Interestingly, Pasteur had not done any experimental studies using the rabies vaccine on animals that had already exhibited clinical signs of rabies, with the exception of an unsuccessful treatment of a rabbit with rabies a few days after Girard’s treatment had begun (Geison, 1995).

Figure 1.2 Timeline of therapy of Girard, Julie-Antoinette Poughon, and Joseph Meister and of experimental studies on dogs with rabies vaccine by Louis Pasteur. (Reproduced with permission from GL Geison in The Private Science of Louis Pasteur, 1995, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, pp 234–256; Copyright Princeton University Press.)

On July 6, 1885 Pasteur initiated treatment of a 9-year-old boy from a village in Alsace, Joseph Meister, who had been severely bitten two days earlier by a rabid dog with a dozen bites or more (some deep) involving his finger, thighs, and calves. He was treated with 13 inoculations of infected rabbit spinal cord material over 11 days, and physician Dr. Jacques-Joseph Grancher actually administered the vaccine. Pasteur used spinal cord tissue because this tissue was associated with a higher viral titer than brain tissue. The spinal cord tissue contained previously passaged virus that had been partially inactivated with progressively shorter periods of desiccation, which ranged from 15 days (first dose) to 1 day (last dose) (Pasteur, 1885). Joseph Meister never developed rabies. Émile Roux w...