- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Molecular Biology and Genomics

About this book

Never before has it been so critical for lab workers to possess the proper tools and methodologies necessary to determine the structure, function, and expression of the corresponding proteins encoded in the genome. Mulhardt's Molecular Biology and Genomics helps aid in this daunting task by providing the reader with tips and tricks for more successful lab experiments. This strategic lab guide explores the current methodological variety of molecular biology and genomics in a simple manner, addressing the assets and drawbacks as well as critical points. It also provides short and precise summaries of routine procedures as well as listings of the advantages and disadvantages of alternative methods.

- Shows how to avoid experimental dead ends and develops an instinct for the right experiment at the right time

- Includes a handy Career Guide for researchers in the field

- Contains more than 100 extensive figures and tables

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Molecular Biology and Genomics by Cornel Mulhardt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Genetics & Genomics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

What Is Molecular Biology?

Publisher Summary

This introductory chapter discusses how molecular biology is better characterized by biochemistry rather than the biology of molecules. Pursuits in the field of molecular biology involve genetic engineering and techniques such as cloning and may be interpreted as being quite adventuresome. Molecular biology deals with nucleic acids, which come in two forms: deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA). The chemical differences between the two substances are minimal. They are both polymers that are made of four building blocks each: deoxynucleotides in DNA and nucleotides in RNA. The nucleotides of RNA are composed of a base constituent (adenine, cytosine, guanine, or uracil), a glucose component (ribose), and a phosphoryl residue, whereby two nucleotides are connected to each other through phosphoglucose bonds. In this way, one nucleotide can be connected to the next, forming a long chain known as a polynucleotide, which is designated as RNA. DNA is formed in almost the same manner. The deoxynucleotides of DNA are composed of a base constituent (adenine, cytosine, guanine, or thymine), two deoxyribose (instead of ribose), and a phosphoryl residue. In molecular biology, experimenters work with a handful of proteins—including polymerases, restriction enzymes, kinases, and phosphatases—in processing nucleic acids, although the functions of these proteins are not fully understood, which is not absolutely necessary as long as they do function.

Gib nach dem löblichen

von vorn Schöpfung anzufangen!

Zu raschem Wirken sei bereit!

Da regst du dich nach ewigen Normen

durch tausend, abertausend Formen,

und bis zum Menschen hast du Zeit.

Yield to the noble inspiration

To try each process of creation,

And don’t be scared if things move fast;

Thus growing by eternal norms,

You’ll pass through many a thousand forms,

Emerging as a man at last.

–Goethe, Faust1

Pursuits in the field of molecular biology involve genetic engineering and techniques such as cloning, and they may be interpreted as being quite adventuresome and almost divine. As a molecular biologist, declaring how you spend your days may garner boundless admiration from some people and disapproval from others. Consequently, you must consider carefully with whom you are speaking before describing your activities. You should not mention how many problems and how much frustration you must endure daily, because one group will be disillusioned, and the other will inevitably ask why you continue to work in this field.

I confess that I like the debates about whether we should clone humans, although the discussion often is not engaged at a scientific level. One individual makes a stupid suggestion, and one half of the media and the nation explain why the cloning of humans may not be justified by any means. It seems much ado about nothing, and I cannot comprehend what advantage it would be for me to clone myself. Why should I wish to invest $75,000 for a small crybaby, whose only common ground with me is that it looks like me as I did 30 years ago, if I could instead come to a similar result in a classic manner for the price of a bouquet of flowers for my wife and a television-free evening?

This example reveals the problems that are associated with molecular biology. Incited by spectacular reports in the media, everybody has his or her own, usually quite extreme, ideas on the benefits or disasters related to this topic. In reality, the picture is deeply distressing. Molecular biology, also known as the molecular world, generally deals with minute quantities of chiefly clear, colorless solutions. There are no signs of ecstatic scholars who have gone wild in the cinematic setting of flickering, steaming, gaudy-colored liquids. The molecular world deals with molecules, evidence for the existence of which has been attempted in many textbooks, although there is generally little more than a fluorescing spot to be seen on the agarose gel. Every procedure seems to take 3 days, and no Nobel Prize is associated with any of them.

Molecular biology is primarily a process of voodoo—sometimes everything works, but usually nothing works. Very unusual parameters seem to play a role in the result of an experiment, which should represent the subject of the research itself—the last, great taboo of modern science. Based on the empirical data, I have come to the realization that the results of an experiment can be calculated as the quotient of air pressure and the remaining number of scribbled note pages in the drawer raised to the power of grandmother’s dog. Until I have been able to verify this experimentally, however, I will continue to limit myself to the classic explanations based on mathematics, which have admittedly enabled this profession to progress quite far.

1.1 The Substrate of Molecular Biology: The Molecular World for Beginners

War es ein Gott, der diese Zeichen schrieb,

die mir das innre Toben stillen,

das arme Herz mit Freude füllen

und mit geheimnisvollem Trieb

die Kräfte der Natur rings um mich her enthüllen?

Was it a God, who traced this sign,

Which calms my raging breast anew,

Brings joy to this poor heart of mine,

And by some impulse secret and divine

Unveils great Nature’s labors to my view!

Molecular biology is by no means the biology of molecules, which is better characterized by biochemistry. Molecular biology is the study of life as reflected in DNA. It is a small, closely knit world that differentiates itself from all other related fields, including zoology, botany, and protein biochemistry. Only a few individuals in the field of molecular biology are biologists, and those who are biologists would be most happy to deny it. If you are not a biologist, be assured that you now find yourself in the best of company and that the small amount of material needed to master this work can quickly be understood.

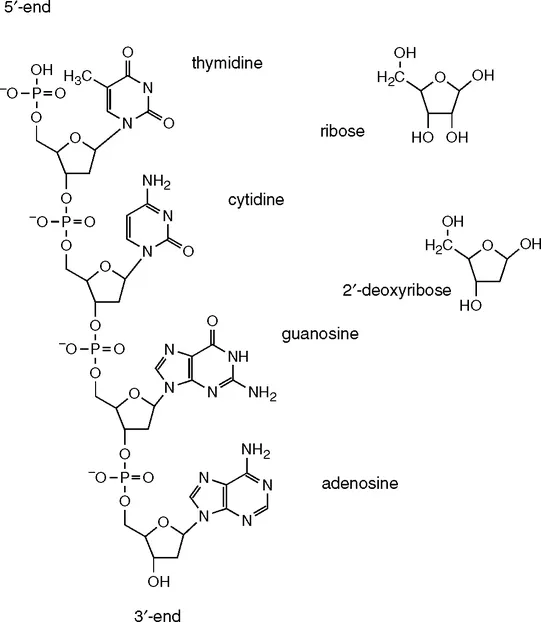

Molecular biology deals with nucleic acids, which come in two forms: deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA). The chemical differences between the two substances are minimal. They are both polymers that are made of four building blocks each, deoxynucleotides in DNA and nucleotides in RNA.

The nucleotides of RNA are composed of a base constituent (adenine, cytosine, guanine, or uracil), a glucose component (ribose), and a phosphoryl residue, whereby two nucleotides are connected to each other through phosphoglucose bonds. In this way, one nucleotide can be connected to the next, forming a long chain known as a polynucleotide, which is designated as RNA. DNA is formed in almost the same manner. The deoxynucleotides of DNA are composed of a base constituent (adenine, cytosine, guanine, or thymine), 2’-deoxyribose (instead of ribose), and a phosphoryl residue.

More details can be found in textbooks of biochemistry, cell biology, or genetics. I limit my comments on these topics to a few aspects that are significant for laboratory practice.

Deoxynucleotide is a tongue twister, which is avoided whenever possible. Researchers instead speak of nucleotides when using these substances in the laboratory, although they generally refer to the deoxy variant.

The names of the nucleotides are based on the names of their bases: adenosine (A), cytidine (C), guanosine (G), thymidine (T), or uridine (U). Many confuse these bases with the nucleotides (Figure 1-1), although this rarely makes a difference in practice. The abbreviations A, C, G, T, and U have been used to immortalize all the DNA and RNA sequences known to the world.

The phosphoryl group of the nucleotides is connected to the 5’ carbon atom of the sugar component. The synthesis of nucleic acid begins with a nucleotide at whose 3’-OH group (i.e., the hydroxyl group at the 3’ carbon atom) a phosphodiester bond connects the phosphate group with the next nucleotide. Another nucleotide can be connected to the 3’-OH group of the nucleotide and so on. Synthesis proceeds in the 5’ to 3’ direction, because a 5’ end and a 3’ end exist at all times, and a new nucleotide is always added to the 3’ end. All known sequences are read from the 5’ end to the 3’ end, and attempts to alter this convention can only create chaos.

If no 3’-OH group exists, it is impossible to connect a new nucleotide. In nature, this situation is rarely observed, although it plays a large role in the sequencing performed in the laboratory. In addition to the four 2’-deoxynucleotides, 2’,3’-dideoxynucleotides are used in DNA synthesis. They can be connected to the 3’ end of a polynucleotide in the normal manner, but because a 3’-OH group is lacking, the DNA cannot be lengthened any further. This principle is essential for understanding sequencing, a subject that will be discussed in more detail later.

Each nucleotide or polynucleotide with a phosphoryl group at its 5’ end can be bonded (ligated) to the 3’ end of another polynucleotide with the aid of a DNA ligase. In this way, even larger DNA fragments can be bonded to one another. Without the phosphoryl group, nothing works, and elimination of a phosphoryl residue with a phosphatase can be used to help inhibit such ligations.

Two nucleotides bonded to one another are known as a dinucleotide, and three together are known as a trinucleotide. If more nucleotides are bonded together in a group, the structure is called an oligonucleotide, and if very many are bonded together, the entire structure is known as a polynucleotide. The boundary between oligonucleotides and polynucleotides is not defined precisely, but oligonucleotides usually are considered to contain fewer than 100 nucleotides.

Whether the structure is a mononucleotide, dinucleotide, oligonucleotide, or polynucleotide, the substance always represents a single molecule, because a covalent bond is formed between each of the initial molecules involved. The length of the chain formed in this way plays no role, because even a nucleic acid that is 3 million nucleotides long is a single molecule.

Polynucleotides have a remarkable and important characteristic: Their bases pair specifically with other bases. Cytosine always pairs with guanine, and adenine pairs with thymine (in DNA) or with uracil (in RNA); no other combinations are functional. The more bases that pair with one another, the more stabile this combination becomes, because hydrogen bonds are formed between the bases of each pair, and the power of these bonds is cumulative. A sequence that pairs perfectly with another sequence is said to be complementary. The nucleic acid sequences of two complementary nucleic acid...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Foreword to the First Edition

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1: What Is Molecular Biology?

- Chapter 2: Fundamental Methods

- Chapter 3: The Tools

- Chapter 4: The Polymerase Chain Reaction

- Chapter 5: RNA

- Chapter 6: Cloning DNA Fragments

- Chapter 7: Hybridization: How to Track Down DNA

- Chapter 8: DNA Analysis

- Chapter 9: Investigating the Function of DNA Sequences

- Chapter 10: Using Computers

- Chapter 11: Suggestions for Career Planning: The Machiavelli Short Course for Young Researchers

- Chapter 12: Concluding Thoughts

- Appendix 1

- Appendix 2

- Index