eBook - ePub

Managing Agricultural Greenhouse Gases

Coordinated Agricultural Research through GRACEnet to Address our Changing Climate

- 572 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Managing Agricultural Greenhouse Gases

Coordinated Agricultural Research through GRACEnet to Address our Changing Climate

About this book

Global climate change is a natural process that currently appears to be strongly influenced by human activities, which increase atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases (GHG). Agriculture contributes about 20% of the world's global radiation forcing from carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide, and produces 50% of the methane and 70% of the nitrous oxide of the human-induced emission. Managing Agricultural Greenhouse Gases synthesizes the wealth of information generated from the GRACEnet (Greenhouse gas Reduction through Agricultural Carbon Enhancement network) effort with contributors from a variety of backgrounds, and reports findings with important international applications.

- Frames responses to challenges associated with climate change within the geographical domain of the U.S., while providing a useful model for researchers in the many parts of the world that possess similar ecoregions

- Covers not only soil C dynamics but also nitrous oxide and methane flux, filling a void in the existing literature

- Educates scientists and technical service providers conducting greenhouse gas research, industry, and regulators in their agricultural research by addressing the issues of GHG emissions and ways to reduce these emissions

- Synthesizes the data from top experts in the world into clear recommendations and expectations for improvements in the agricultural management of global warming potential as an aggregate of GHG emissions

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Managing Agricultural Greenhouse Gases by Mark Liebig,A.J. Franzluebbers,Ronald F Follett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Tecnologia e ingegneria & Biologia. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

BiologiaSection 1

Agricultural Research for a Carbon-Constrained World

Chapter 1 Agriculture and Climate Change

Chapter 2 GRACEnet

Chapter 1

Agriculture and Climate Change: Mitigation Opportunities and Adaptation Imperatives

1USDA-ARS, Northern Great Plains Research Laboratory, Mandan, ND

2USDA-ARS, J. Phil Campbell Sr., Natural Resource Conservation Center, Watkinsville, GA

3USDA-ARS, Soil Plant Nutrient Research Unit, Ft. Collins, CO

Chapter Outline

Introduction

Mitigating and Adapting To Climate Change

Mitigation

Enhance Soil C Sequestration

Improve N-use Efficiency

Increase Ruminant Digestion Efficiency

Capture GHG Emissions from Manure and Other Wastes

Reduce Fuel Consumption

Adaptation

Increase Crop Diversity

Implement Efficient Irrigation Methods

Adopt Integrated Pest Management (IPM)

Improve Soil Management

Co-Benefits

Summary

NB: The U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service is an equal opportunity/affirmative action employer and all agency services are available without discrimination.

Abbreviations: C, carbon; CO2, carbon dioxide; CO2e, carbon dioxide equivalent; GWP, global warming potential; GRACEnet, Greenhouse gas Reduction through Agricultural Carbon Enhancement Network; GHG, greenhouse gas; IPCC, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Ch4, methane; N, nitrogen; N2O, nitrous oxide.

Introduction

Carbon (C) and nitrogen (N) are critically important elements for sustaining life on earth. The balance of photosynthesis and respiration, along with methanotrophy and methanogenesis, regulate the presence of C among the atmosphere, biomass, and soil. Nitrogen, as an integral part of nucleotides and proteins, often limits net primary production (Schlesinger, 1997). Accordingly, C and N—and the key metabolic processes that regulate their transfer between compartments in the biosphere—affect the production of food, feed, fiber, and fuel needed for our daily lives.

Carbon and N also play important roles in regulating environmental quality. Reactive forms of both elements—when present in excess of biological requirements—can adversely impact environmental quality across a range of spatial scales (Vitousek et al., 1997; Janzen, 2005). Balancing concurrent needs of food security and a healthy environment is a crucial challenge given projections for human population growth (Godfrey et al., 2010). As such, documenting C and N dynamics within the biosphere will be essential to assess our relative success in achieving these concurrent goals.

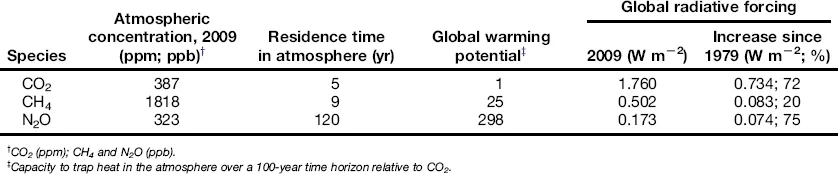

Agricultural production contributes to C and N dynamics through the flux of carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4,), and nitrous oxide (N2O), which represent the three greenhouse gases (GHG) principally associated with agricultural activities (Paustian et al., 2006). These three GHGs differ considerably in their atmospheric concentration, residence time in the atmosphere, global warming potential, and radiative forcing (Table 1.1). Carbon dioxide, the most abundant of the three GHGs, is fixed by plants and a portion of it is respired back to the atmosphere. Destruction of plant material through harvesting, natural decay, or burning also contributes to CO2 emissions through microbial respiration and/or direct combustion. Agricultural-induced fluxes of CH4 include emissions from ruminant livestock, flooded rice paddies, wetlands, livestock manure, and burned biomass, and, conversely, uptake by methanotrophic bacteria in soil under aerobic conditions. Fluxes of N2O from agriculture are typically unidirectional through processes of nitrification or denitrification, with emissions most prevalent from cultivated soils, livestock manure, and biomass burning (Schlesinger, 1997; Greenhouse Gas Working Group, 2010; Climate Change Position Statement Working Group, 2011).

TABLE 1.1. Attributes of atmospheric CO2, CH4, and N2O (IPCC, 2007; NOAA, 2011)

Agricultural contributions to total GHG emissions in the U.S. are relatively small, accounting for approximately 6.3% of total emissions in 2009, or 419 of 6633 Tg CO2e yr−1 (U.S.-EPA, 2011). Of the three agricultural GHGs, emissions of CH4 and N2O are dominant, and considered in the U.S.-EPA Agriculture report exclusive of CO2 emissions and removals. Methane emissions from enteric fermentation and manure management account for 96% of the total CH4 emissions from agriculture (189 Tg CO2e yr−1), and are the second and fifth largest anthropogenic sources of CH4 emissions in the U.S., respectively. Nitrous oxide emissions from soil management practices make up 92% of agricultural N2O emissions (205 Tg CO2e yr−1), and are by far the largest source of anthropogenic N2O emissions in the U.S., accounting for 69% of the total. Emissions of CO2 from agriculture are largely constrained to fossil fuel combustion, land conversion to cropland, lime application, and urea fertilization (Σ = 83.1 Tg CO2 yr−1). However, agricultural practices in the U.S. sequester approximately 49.3 Tg CO2 yr−1 through conversion of cropland to grassland, increased use of conservation tillage and continuous cropping, and improved management of organic fertilizers (U.S.-EPA, 2011).

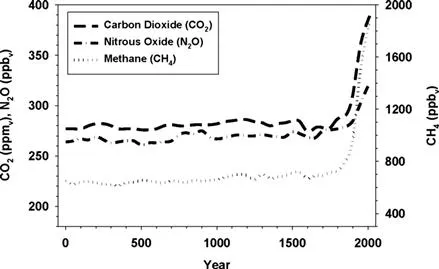

Atmospheric concentrations of GHGs have increased significantly since the mid-1700s (Figure 1.1). This increase has been driven mainly by fossil fuel combustion and land-use change resulting from human activities. The capacity of GHGs to trap outgoing long-wave radiation and emit it back to the earth’s surface as heat has contributed to global-scale climate change (Paustian et al., 2006). Direct effects of climate change are significant and long-lasting, and include an increase in global average surface temperature, altered precipitation patterns, reduced snow cover, increased sea level rise, and ocean acidification (IPCC, 2007). These projected changes will have broad effects on agriculture (Follett, 2012). Shifts in vegetation zones, increased potential for droughts and floods, elevated rates of soil erosion, and increased photosynthetic rates (from higher CO2 concentration) represent potential outcomes affecting agriculture, as well as how agriculture affects the broader environment (Climate Change Position Statement Working Group, 2011; Janzen et al., 2011). Moreover, positive feedbacks from climate change—such as accelerated soil organic matter decomposition and release of CH4 from northern soils—could exacerbate such effects.

FIGURE 1.1 Concentrations of atmospheric CO2, CH4, and N2O during the previous two millennia.

(after IPCC, 2007)

Challenges to agriculture associated with climate change are not short term. Momentum in human population growth through the mid-21st century will almost surely result in increased rates of GHG emissions, particularly from the energy sector (IPCC, 2007). Furthermore, even if GHG emissions were to stabilize or decrease, consequences from global climate change would continue well into the next century due to momentum from climate processes and feedbacks (IPCC, 2007; Armour and Roe, 2011). This reality has led to an increased awareness that agriculture has a crucial role to play in responding to climate change, both in mitigating its causes and adapting to its impacts (Climate Change Position Statement Working Group, 2011).

Mitigating and Adapting To Climate Change

Recent reviews have provided extensive lists documenting how agricultural practices can mitigate and/or adapt to climate change (CAST, 2011; Eagle et al., 2010; Greenhouse Gas Working Group, 2010; Delgado et al., 2011; Lal et al., 2011; Climate Change Position Statement Working Group, 2011). Broadly, suggested GHG mitigation practices either contribute to soil organic C (SOC) accrual, reduce CH4 and/or N2O emissions, or reduce fuel consumption. Adaptation responses to climate change address agroecosystem adjustments to alterations in environmental conditions (Climate Change Position Statement Working Group, 2011). Such responses extend beyond regulating GHG fluxes through management, to address broader themes related to reducing negative impacts on agroecosystems while taking advantage of potential benefits associated with climate change.

Mitigation

The ASA-CSSA-SSSA Greenhouse Gas Working Group provided five broad strategies for mitigating agricultural GHG emissions (Greenhouse Gas Working Group, 2010):

1. Enhance soil C sequestration;

2. Improve N-use efficiency;

3. Increase ruminant digestion efficiency;

4. Capture GHG emissions from manure and other wastes; and

5. Reduce fuel consumption.

These five strategies are well established to either remove GHGs from the atmosphere (1) or reduce GHG emissions from known sources (2, 3, 4, 5). Because each mitigation strategy has been thoroughly addressed in previous reviews, only a synopsis of each is provided here.

Enhance Soil C Sequestration

Enhancement of soil C sequestration can be achieved by maintaining plant residues on the soil surface, minimizing soil disturbance and erosion, adopting complex cropping systems that provide continuous ground cover, and applying C-rich substrates to soil (Lal and Follett, 2009). The magnitude and rate of soil C sequestration is dependent on various edaphic and climatic factors that directly affect biomass productivity and C retention in soil (Brady and Weil, 1999). In some instances, management practices have had variable effects on soil C dynamics and CH4 and N2O flux, resulting in either enhancing (e.g. increased soil C, decreased N2O emission) or negating (e.g. increased soil C, increased N2O emission) net GHG emissions. Such variable responses emphasize the importance of inclusive GHG assessments to ascertain GHG tradeoffs associated with management (Eagle et al., 2010).

Improve N-use Efficiency

Improving N-use e...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Contributors

- Executive Summary

- Section 1. Agricultural Research for a Carbon-Constrained World

- Section 2. Agricultural Management and Soil Carbon Dynamics

- Section 3. Agricultural Management and Greenhouse Gas Flux

- Section 4. Modeling to Estimate Soil Carbon Dynamics and Greenhouse Gas Flux from Agricultural Production Systems

- Section 5. Measurements and Monitoring: Improving Estimates of Soil Carbon Dynamics and Greenhouse Gas Flux

- Section 6. Economic and Policy Considerations Associated with Reducing Net Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Agriculture

- Section 7. Looking Ahead: Opportunities for Future Research and Collaboration

- Index

- Color Plates