![]()

Part 1

The Elements: Data, Variables, Concept, and the Server

Part I. The Elements: Data, Variables, Concept, and the Server

Chapter 1 Structure–Activity Databases for Medicinal Chemistry

Chapter 2 The Variables

Chapter 3 Variables and Data

Chapter 4 The AtlasCBS Application

![]()

Part I. The Elements: Data, Variables, Concept, and the Server

The vast amount of data relating the affinity of small molecules (ligands) to the biological molecules to which they have any activity (targets) is now stored in several public and private databases of considerable complexity and magnitude (Structure–Activity or SAR Databases: BindingDB, PDBBind, ChEMBL, PubChem, WOMBAT, and others). These data comprise the currently known chemicobiological space (CBS). Although comprehensive in scope and extent, the databases themselves do not provide dramatic insights as to the basic principles that govern the interaction between ligands and targets, nor do they provide a graphic road map to guide the drug-discovery process.

Ligand efficiency indices (LEIs) represent a novel way to look into the affinity of the ligands toward their targets by taking into consideration the affinity, size, polarity, and other physicochemical properties using combined variables. The various formulations are presented and discussed and a combined framework is introduced that permits graphing the content of the SAR databases in an atlas-like representation. A web tool (AtlasCBS) is described that allows the user to map CBS online and summarizes the content of those databases in efficiency planes. This representation is akin to an atlas of CBS that could guide drug-discovery efforts in the future.

![]()

Chapter 1

Structure–Activity Databases for Medicinal Chemistry

1.1 PDB

1.2 PDBBind, MOAD

1.3 ChEMBL

1.4 WOMBAT

1.5 DrugBank

1.6 BindingDB

1.7 PubChem

1.8 Proprietary Databases

1.9 Perspective

1.10 Discussion

On October 30, 2011, the community of macromolecular crystallographers and structural biologist gathered at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the origins of the Protein Data Bank (PDB), the most notable of the three-dimensional structural repositories of macromolecules of biological interest. It had been 40 years since the concept of a public access collection of protein structures took hold in the incipient community for protein crystallographers. The spectacular growth and development of this global resource has been described by one of the pioneers of the PDB1. The idea of a common depository (a database) of crystallographic results relevant to the biological and chemical community was a visionary concept. These were the days well before the Internet was invented and a “data set,” a protein structure, was contained in a box of about one thousand IBM computer cards (80 columns across), one card per atom, with the three Cartesian coordinates for each atom.

Since then, many databases have developed within the scientific community at large and the advent of the Internet has given these public resources tremendous flexibility of content, access, and interrelation. For the purpose of drug discovery, three kinds of databases are of special relevance: chemical, biological, and the most recent ones that relate both. Chemical databases typically store small molecule structures of both drug and nondrugs, usually linked to the commercially available chemical compounds and they represent a tremendous resource for virtual or experimental screening (e.g., ZINC)2. The content of biological databases is predominantly gene nucleotide sequences and/or protein amino acid sequences as they relate to their biological function. Most important among them is the originally named SwissProt3, which now contains over half a million protein sequences and has evolved into a formidable bioinformatics resource to become the Swiss Institute for Bioinformatics (SIB) (www.isb-sib.ch). The increasing accumulation of structure–activity data, originating from various in vitro and in vivo assays of a myriad of small molecules, targeting a growing number of biological macromolecules from an increasing number of biological targets, has resulted in databases that are referred to as large-scale SAR databases. These databases typically relate a document (D, journal or patent) reporting the data or the result(s) from one or various assays (A) of a certain compound (C, small molecule), on a certain protein target (P) with a quantitative result (R), given in concrete units4,5. Various SAR databases obtain (or extract) these data and organize the content in different ways to facilitate access to the information. This chapter provides an overview of the most prominent databases (private and public) of interest for drug discovery; it is by no means meant to be exhaustive. It focuses on the databases most relevant to the drug-discovery community and the ones that have been used for the development of the ideas and concepts presented here.

The most veteran public chemical databases, Chemical Entities of Biological Interest (ChEBI) and PubChem, made their appearance in 2004 and have grown and developed considerably since that time. ChEBI is a database of endogenous and synthetic bioactive compounds that features a chemical ontology classification of the chemical entities6, 7. PubChem is a massive open repository of experimental data that is organized in three distinct databases: PubChem Substance, PubChem Compound, and PubChem BioAssay. Only the PubChem Compound branch contains the strictly chemical information with links to the chemical substances and bioassay data. It also provides links to the literature citations via PubMed. From these initial efforts, a large variety of databases of interest to the drug-discovery community have matured. A brief description of the most relevant (public and private) SAR databases follows. Their order reflects the historical path that the different databases have played in the development of the ideas presented in this book.

1.1 PDB

As a protein crystallographer, my early contact with databases originates from the existence of the PDB. The PDB is a unique database because since its inception, the focus has been to make the three-dimensional structures of proteins and macromolecules available to the community of structural biologists at large. In the early years of protein crystallography, the solution of each new structure was the result of several years of hard labor by a committed group of researchers and the concept of making those results publicly available was not an obvious thought. Generally speaking, the growth of the PDB has been exponential through the years with the number of entries doubling approximately every 2.75 years8. However, there was a slow down of the deposition rates in the mid-1980s related to the relevance and importance of macromolecular structures for drug discovery. Details of the history of the PDB can be found in the historical perspective by Berman1 and a more detailed analysis of the deposition rates can be found in a brief essay commemorating the 40th anniversary of its birth8.

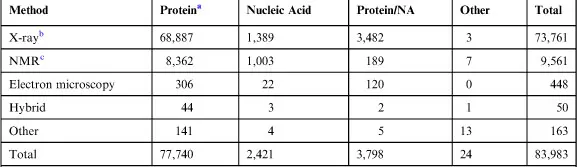

Currently, the PDB is the central repository of macromolecular structures including proteins, nucleic acids, and virus structures, as well as a rather large number (>6,000) of protein–ligand complexes, determined by experimental methods. Ligands are any small molecule that binds to the protein/macromolecule in the crystalline environment. Although the vast majority of the structures have been determined by X-ray crystallographic methods, entries now also include structures determined by alternative physicochemical techniques such as nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and high resolution electron microscopy. It should be noted that although at the beginning the PDB was physically located at Brookhaven National Laboratory (Long Island, NY), since 2003, the PDB is a global organization called the Worldwide PDB9 (www.wwpdb.org). It has four centers distributed on three continents: Research Collaborative for Structural Bioinformatics (RCSB) and the BioMagResBank (BMRB) in the USA, the Protein Data Bank Japan (PDBj) and the Protein Data Bank in Europe (PDBe; PDBe.org). The four wwPDB partners accept, process, and curate new structures (further details can be found at Velankar et al.10). A quick consultation of one of the PDB websites (www.rcsb.org) reveals that at the time of writing, the number of entries is 83,983 (13,887 target–ligand complexes). Of those structures, 73,761 were determined by X-ray methods, 9,561 by NMR, and 448 using electron microscopy (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1

PDB Current Holdings

aProtein includes protein, viruses, and protein–ligand complexes. As of August 21, 2012, 5 p.m. PDT.

b63,188 structures in the PDB have a structure factor file.

c6,868 structures have an NMR restraint file. 628 structures have a chemical shifts file.

Each entry is defined by an alphanumeric access code (i.e., 1A4G) that gives access to the atomic coordinates, crystallographic details of the structure determination including the structure factors if available, and a few key references to the published report of the structure. From these key items, the PDB resource branches off to provide a tremendous number of options (too many to list here) that help the user digest, expand, and relate the information on the protein (target and related entries) and the available ligands (if any) including salts, ions, precipitants, and other pertaining information. The PDB is a key hub of information consulted routinely by other databases that relate proteins (targets) to the ligands interacting with them.

1.2 PDBBind, MOAD

The expanding knowledge of biomacromolecular structures (including complexes) and the advances in computational and in silico tools for drug discovery prompted the almost simultaneous development of two databases derived from PDB: PDBBind11 and MOAD (Mother of all Databases)12. These resources are based on the curated and extended content of the PDB with the specific purpose of aiding computational chemists to test, validate, and improve their software tools.

In both cases, the objective was to extract a subset of well-refined structures from the existing target–ligand complexes in the PDB and complement these data with the corresponding binding affinity data (Kd, Ki, and IC50) from the primary references. A very importa...