- 398 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Fossil Fungi

About this book

Fungi are ubiquitous in the world and responsible for driving the evolution and governing the sustainability of ecosystems now and in the past. Fossil Fungi is the first encyclopedic book devoted exclusively to fossil fungi and their activities through geologic time. The book begins with the historical context of research on fossil fungi (paleomycology), followed by how fungi are formed and studied as fossils, and their age. The next six chapters focus on the major lineages of fungi, arranging them in phylogenetic order and placing the fossils within a systematic framework. For each fossil the age and provenance are provided.

Each chapter provides a detailed introduction to the living members of the group and a discussion of the fossils that are believed to belong in this group. The extensive bibliography (~ 2700 entries) includes papers on both extant and fossil fungi. Additional chapters include lichens, fungal spores, and the interactions of fungi with plants, animals, and the geosphere. The final chapter includes a discussion of fossil bacteria and other organisms that are fungal-like in appearance, and known from the fossil record. The book includes more than 475 illustrations, almost all in color, of fossil fungi, line drawings, and portraits of people, as well as a glossary of more than 700 mycological and paleontological terms that will be useful to both biologists and geoscientists.

- First book devoted to the whole spectrum of the fossil record of fungi, ranging from Proterozoic fossils to the role of fungi in rock weathering

- Detailed discussion of how fossil fungi are preserved and studied

- Extensive bibliography with more than 2000 entries

- Where possible, fungal fossils are placed in a modern systematic context

- Each chapter within the systematic treatment of fungal lineages introduced with an easy-to-understand presentation of the main characters that define extant members

- Extensive glossary of more than 700 entries that define both biological, geological, and mycological terminology

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fossil Fungi by Thomas N Taylor,Michael Krings,Edith L. Taylor in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

Fungi are fundamental to the health and success of almost every ecosystem in the world today, and they certainly played equally important roles in ancient ecosystems. We now know that there is an extraordinary abundance of fungal remains in the fossil record; however, systematic studies of fungal lineages based on fossils are lacking to date, owing primarily to the inherent problems and limitations connected to the fossil record of the fungi. Moreover, when fungi were reported in the past they were rarely placed within a broader context. Today, however, there is an increasing interest in fossil fungi and their importance in ancient ecosystems, which has been stimulated by a generally growing scientific awareness of the microbial world and the interrelatedness of all organisms. This book chronicles the fossil record of fungi through geologic time, places them within a systematic context where possible, and describes various types of fungal associations that existed in ancient ecosystems. Paleomycology is defined and discussed within the historical context of both extant and fossil fungi, and linked to other closely interrelated disciplines dealing with fungi and fungus-like microorganisms.

Keywords

anamorph; biodiversity; decomposition; fungi; fossil; geobiology; heterotrophs; holomorph; mutualists; paleomicrobiology; paleomycology; teleomorph; geologic time

Fungi are extraordinary. Although fungi represent the largest life forms on Earth (Angier, 1992), and are instrumenta to the health and success of almost every ecosystem, they are perhaps the most underappreciated group of organisms. There are approximately 100,000 species of fungi and fungal-like organisms currently recognized, and as a result of molecular techniques it is estimated that there may be more than 5 million species of fungi inhabiting the Earth (e.g. Blackwell, 2011). Since there are estimated to be more than 400,000 species of flowering plants (angiosperms), the group we depend upon for food (e.g. Joppa et al., 2011), this means that there are more than 10 times more fungi than angiosperms. To realize and accurately document the biodiversity of fungi in the future it will be as important to develop and integrate data-based platforms (e.g. Halme et al., 2012) as it will be to document fungi in tropical forests and unexplored habitats (Hawksworth, 2004). Fungi impact just about every aspect of life and have played a major role in the evolution of life on land (e.g. Blackwell, 2000). In fact, the colonization of land by plants is hypothesized to have occurred as the result of symbiotic interaction(s) between a fungus and a photosynthesizing organism. Today this association continues in the form of mycorrhizae, which occur in and around the roots of vascular plants and increase nutrient uptake in an estimated 90% or more of all plant species.

Fungi range from single celled to complex multicellular organisms and can be found in all aerobic ecosystems where they colonize numerous substrates and perform multiple functions, some of which are poorly understood (e.g. Cantrell et al., 2011). For example, they occur in habitats ranging from Antarctica (e.g. Onofri et al., 2007; Kochkina et al., 2012) to salt flats to laminated organo-sedimentary ecosystems termed microbial mats. They have even been reported as epiphytes on unicellular or multicellular plant hairs or trichomes (Pereira-Carvalho et al., 2009), in deep-sea ecosystems (e.g. Schumann et al., 2004; Le Calvez et al., 2009; Nagano and Nagahama, 2012), and in 100 m of deep sea mud (Biddle et al., 2005). Fungi are the primary degraders of complex organic compounds such as lignin and cellulose and, through this recycling, are important in returning minerals to the soil. As a result of decomposition, carbon dioxide is returned to the atmosphere. They are especially important decomposers in acidic soils where bacteria often cannot exist. Fungi also bind soil particles to their mycelium, thus contributing to soil structure. In all of these functions they are crucial in the maintenance of the biosphere. Fungi, together with soil fauna, roots, and other microorganisms, are major drivers of ecosystems and in this capacity are involved in the critical processes of landscape sustainability, including nutrient cycling, in which they accumulate, store, and distribute minerals and carbon (e.g. Johnston et al., 2004). Most are filamentous, which allows them to readily explore and exploit new habitats including their own parental hyphae (e.g. Gadd, 2007).

Because fungi are carbon heterotrophs they have, by necessity, mastered various levels of cooperation with other organisms: they partner with certain types of algae and cyanobacteria to form lichens, and their intimate relationships with land plants include mycorrhizal associations. They also occur as endophytes in some vascular plants and in such cases can be involved in contributing to pathogen resistance. What may be interpreted as the “dark side” of the fungal kingdom is that as plant pathogens they impact broad areas of agriculture by infecting all major crop plants and producing various mycotoxins involved in food contamination and in some cases human disease. Fungi are also known to negatively affect animals and humans as causative agents of diseases (e.g. Sternberg, 1994; Fisher et al., 2012). One of these diseases, chytridiomycosis, has made it into the news because it is believed to have caused the decline and even extinction of some amphibian populations on several continents (e.g. Longcore et al., 1999; Weldon et al., 2004).

In buildings, fungi and other microbes contribute to altering and erasing cultural structures by deteriorating historical stone in the form of statues, tombstones, historic buildings, and archaeological sites (McNamara and Mitchell, 2005; Mitchell and McNamara, 2010; Steiger and Charola, 2011). In addition, microbial activities and fungi are involved in the deterioration of paintings, wood, paper, textiles, metals, waxes, polymers, and various types of coatings (Koestler et al., 2003; Martin-Sanchez et al., 2012). Fungi also show no respect for some of the “pillars” of our modern society such as utility poles (Wang and Zabel, 1990).

Fungi also enter into mutualistic associations with animals; some even thrive within the animal, in anaerobic environments (Mountford and Orpin, 1994). Especially interesting are fungi that play a pivotal role in the rumen by physically and enzymatically attacking the fibrous plant material ingested by the ruminant animal (e.g. Kittelmann et al., 2012). By breaking down plant cell wall carbohydrates, such as cellulose and hemicellulose, these anaerobic fungi deliver readily accessible nutrients, mainly acetate, propionate, and butyrate, to their ruminant hosts (e.g. Gordon and Phillips, 1998).

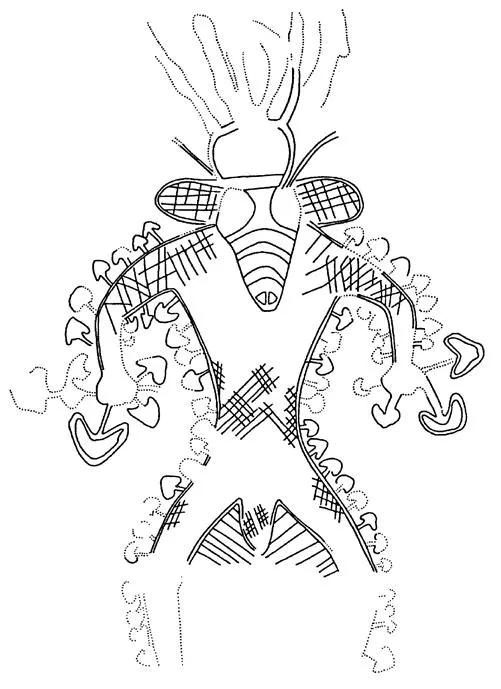

Fungi affect our lives in innumerable ways; some are even believed to have shaped civilizations (e.g. Money, 2007; Dugan, 2008). For example, mushrooms are quite frequently depicted in ancient, medieval, and modern fine art. A group of ethnomycological rock paintings in the Sahara Desert (Tassili n’ Ajjer National Park, Algeria) – the work of pre-Neolithic early hunter-gatherers some 7,000–9,000 years old – shows the offering of mushrooms, and large masked “gods” covered with mushrooms, suggestive of an ancient hallucinogenic mushroom cult (Figures 1.1, 1.2). These paintings may reflect the most ancient human culture yet documented in which the ritual use of hallucinogenic mushrooms is explicitly represented (Samorini, 1992). The Temptation panel in Mathias Grünewald’s famous Isenheim Altarpiece, painted between 1510 and 1515, is believed to represent a depiction of ergot poisoning from rye flour contaminated by the fungus Claviceps purpurea (e.g. Battin, 2010). Ergot poisoning has also been suggested to be the reason for the strange behavior of women accused of witchcraft in Salem, Massachusetts Colony, in the late 1690s (Caporael, 1976), although some have refuted this hypothesis (Spanos and Gottlieb, 1976). Ergotism is known to cause jerky movements, which are characteristic of Sydenham’s chorea or St. Anthony’s fire, as it was called in the Middle Ages (Lapinskas, 2007). Today fungi are also used in criminal investigations, i.e. forensics (Hawksworth and Wiltshire, 2011).

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- About the Authors

- 1. Introduction

- 2. How Fungal Fossils Are Formed and Studied

- 3. How Old are the Fungi?

- 4. Chytridiomycota

- 5. Blastocladiomycota

- 6. Zygomycetes

- 7. Glomeromycota

- 8. Ascomycota

- 9. Basidiomycota

- 10. Lichens

- 11. Fungal Spores

- 12. Fungal Interactions

- 13. Bacteria and Fungus-Like Organisms

- Glossary

- References

- Index

- Chart