- 636 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Colorants for Non-Textile Applications

About this book

This volume examines the chemistry of natural and synthetic dyes produced for non-textile markets, where much new basic research in color chemistry is now taking place.The first group of chapters covers the design, synthesis, properties and application technology pertaining to dyes for digital printing and photography. The reader will be pleased with the breadth and depth of information presented in each case. Of particular interest is the discussion of strategies for the design of dyes in these categories, with emphasis on enhancing technical properties. In view of certain new developments, the ink-jet chapter includes results from studies pertaining to dyes for textiles.The three chapters comprising Section II of this volume cover the broad subject of dyes for food, drug and cosmetic applications and then provide an in-depth look at dyes for biomedical applications and molecular recognition. The chapter on dyes for molecular recognition places emphasis on applications in the biological sciences, including sensory materials and artificial receptors. While the former two topics have been covered elsewhere in the past, the present chapters are unequalled in scope.Section III provides an in-depth review of the design of laser dyes and dye-based functional materials. In the first of the two chapters, the major principles of laser operation are summarized. This is followed by a discussion of spectroscopic properties, such as activation and deactivation of absorbed light by laser dyes. Approaches to the development of new laser dyes are presented. The second chapter pertains to the synthesis of dicyanopyrazine-based multifunctional dyes. The visible and fluorescence spectra of these dyes in solution and the solid state are correlated with their three-dimensional molecular structures. Molecular stacking behavior and solid state properties of these "multifunctional" dye materials are presented.The final group of chapters pertains to natural dyes and dyes for natural substrates. In recent years, the impression among certain consumers that "natural" is better/safer has generated much interest in the use of natural dyes rather than synthetics. This has led to a few short discussion papers in which the environmental advantages to using natural dyes have been questioned. The initial chapter in this group provides both a historical look at natural dyes and a comprehensive compilation of natural dye structures and their sources. Though natural dyes are of interest as colorants for textiles, selected ones are used primarily in food and cosmetics.Chapter ten provides an update on the author's previous reviews of structure-color-relationships among precursors employed in the coloration of hair. Chemical constitutions characterizing hair dye structures are presented, along with a summary of available precursors and their environmental properties. Similarly, the chapter on leather dyes covers constitutions and nomenclature, in addition to providing interesting perspectives on the origin and use of leather, the dyeing of leather, and key environmental issues.This volume is concluded with another look at colors in nature. In this case, rather than revisiting colors in plant life, an interesting chapter dealing with color in the absence of colorants is presented. Chapter twelve covers basic concepts of color science and illustrates how 3-D assemblies leading to a plethora of colors are handled in nature. It is our hope that this atypical "color chemistry" chapter will invoke ideas that lead to the design of useful colorants.The chapters presented in this volume demonstrate that color chemistry still has much to offer individuals with inquiring minds who are searching for a career path. This work highlights the creativity of today's color chemists and the wide variety of interesting non-textile areas from which a career can be launched.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Natural Dyes

1 INTRODUCTION AND HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

Back to nature - a road to the future?

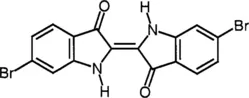

1.1 Isotins

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Preface

- Contributors

- I: PRINTING AND IMAGING TECHNOLOGIES

- II: FD&C AND MEDICAL DYES

- III: FUNCTIONAL MATERIALS

- IV: NATURAL COLOR/SUBSTRATES

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app