![]()

Chapter 1. Measuring the Unexpected - Understanding Economic Capital

In this chapter we introduce economic capital: what it is and what the key underlying concepts are. The origin of economic capital usually is traced back to the late 1970s, when Bankers Trust introduced the RAROC (risk-adjusted return on capital) concept for the evaluation of the profitability of its transactions, using economic capital as uniform measure of risk.[1] Since then, an increasing number of banks have adopted economic capital and RAROC in their decision making. Subsequently, other financial institutions such as insurance companies have caught on to the concept.

When tracing back to the roots of economic capital, an important development was the growth of the trading activities, and in particular the trading of derivative instruments, by financial institutions. This increased the sensitivity of a bank's profit to market variables such as interest rates, exchange rates, and equity prices. To manage these risks, value-at-risk (VaR) models were developed to measure the worst loss that can be incurred from holding a portfolio of securities over a given time and with a specified probability. As the experience of banks with these models grew, regulators became comfortable to allow their use to determine how much capital a bank should hold as buffer against these risks.[2]

Up to that moment, credit risk management did not make much use of quantitative methods. However, the growth of the credit derivative market introduced market risk elements into the credit arena. Modelers started to apply VaR-like models to credit risk, which was still the single most important risk type for most banks. The innovation of Bankers Trust was to use economic capital in performance management by adjusting returns for the economic risks associated with an activity or transaction. Although the fate of Bankers Trust, which was taken over in 1998 by Deutsche Bank after suffering heavy losses, indicates that economic capital and RAROC are no guarantee for success, the underlying ideas proved to be conceptually so appealing that many others continued with its further development and use.

The appeal of economic capital was enhanced by the growth in scale and complexity of many financial institutions, because as a comprehensive risk measure it can be used to monitor and manage the risks efficiently and consistently across the organization. The scope gradually has been extended from market and credit risk to cover all material risks to which an institution is exposed.

The actual use of economic capital was made possible because of the tremendous increase in the power of computers and associated possibilities of information technology. This has enabled the efficient handling of large data sets and performance of complex financial calculations in a fast manner, both of which are crucial for economic capital calculations.

In Section 1.1, we will explain what economic capital intends to measure, and how it relates to the available capital of an institution. Section 1.2 introduces the concepts of expected and unexpected loss, and we indicate their relationship with economic capital. In Section 1.3 we review two conceptual issues related to economic capital as risk measure. The first one concerns the distinction between risk and uncertainty, and we discuss how and to what extent economic capital can reflect both. The second issue concerns a property that one would like any risk measure to possess, but that economic capital (and, in fact, any type of value-at-risk measure) could violate. As we will discuss, this violation does not tend to cause problems in realistic settings, however. Although we believe that economic capital is a valuable and important risk measure for financial institutions, no single risk measure can capture the full spectrum of risks that an institution faces. In Section 1.4 we review reasons for, and examples of, other risk measures that financial institutions use in addition to economic capital.

1.1. What Is Economic Capital?

The capital of a firm protects the firm against insolvency in case the difference in value between its assets and its liabilities decreases. Such a decrease can occur if the value of the liabilities increases more than the value of the assets, or if the value of the assets decreases more than the value of the liabilities. Insolvency occurs if the value of the assets falls below the value of the liabilities and the amount of capital becomes negative. Assuming a given level of capital, the more volatile the difference in value between assets and liabilities is, the more likely it is that insolvency will occur. Increasing the amount of capital will decrease the likelihood of insolvency, but it will not be possible to prevent insolvency with 100 percent certainty. This would also not be an attractive proposition for the providers of capital, because they want to earn an attractive return on their investment. Hence, capital will protect a firm only against insolvency with a certain probability. This probability typically is referred to as the confidence level.

Economic capital represents an estimate of the worst possible decline in the institution's amount of capital at a specified confidence level, within a chosen time horizon. As such, it is a direct function of the risks to which an institution is exposed. If the confidence level at which economic capital is calculated equals the probability with which an institution wants to remain solvent over the chosen time horizon, then economic capital can be viewed as the amount of capital that an institution should possess. The confidence level and time horizon have to be specified by the institution in order to make the definition operational. We will discuss this in Chapter 3.

Financial institutions will not be able to operate normally long before they become insolvent. Once doubts arise whether the amount of capital of an institution is sufficient in relation to the institution's risks, investors, depositors, clients, and other financial institutions will sell the stock, withdraw money, and stop doing business with the institution. This will cause immediate continuity problems. Hence, financial institutions typically do not fail because their capital is depleted, but because the probability of potential capital depletion is deemed too high. It is thus crucial for a financial institution to ensure that its capital is large enough that the probability of insolvency is sufficiently low. This is where economic capital can help to prevent an institution's failure, on which we will elaborate in Chapter 2.

The adjective economic in economic capital reflects that the aim of economic capital is to measure potential changes in the economic value of assets and liabilities, as opposed to changes in value that are determined by accounting rules. The choice for economic values relates to the fact that most firms use economic capital as a measure of risk in risk-return evaluations of their activities. Such risk-return evaluations typically aim to maximize value for the firm's shareholders, and shareholders will focus on the economic value of a firm as opposed to its value according to accounting rules. This obviously presupposes that shareholders are able to determine the economic value of a firm, and the extent to which it differs from the accounting value, something that may not in all cases be straightforward. We will see in Chapter 3 that there will be some tension in the precise definition of economic capital depending on whether economic capital is used in the context of solvency assessment or shareholder value maximization. Differences between accounting values and economic values for assets and liabilities contribute to this tension.

1.2. Expected and Unexpected Losses

When defining economic capital for financial institutions, we need to distinguish between expected and unexpected losses. In the course of doing business, a financial institution expects to incur a certain amount of losses. From experience, a bank knows that there will be a number of customers who will not be able to repay in full the money that was lent by the bank, giving rise to credit losses. Similarly, insurance companies expect to face payouts on a certain number of insurance policies in the normal course of business. In addition, both banks and insurers will account for a certain amount of operational losses to occur. The amount that an institution expects to lose is called the expected loss.

Expected loss can be viewed as a cost of doing business. Consequently, the pricing of products will incorporate a margin to compensate for expected losses. Otherwise, a firm would structurally lose money. We can thus reasonably assume that the pricing of products covers expected losses, and there is therefore no need to hold capital for expected losses. In fact, expected loss does not represent risk, as it constitutes the amount of loss that a financial institution should anticipate to incur.

In any period, however, actual losses will either be higher or lower than the expected amount of losses. Statistically speaking, the probability of ending up exactly with the expected amount of losses is almost zero. To the extent that actual losses are higher than the expected losses, we call them unexpected losses. The size of the unexpected losses is what constitutes risk for a financial institution. If unexpected losses are not too large, they may be compensated by the profit margin in the product pricing if this profit margin is larger than strictly necessary to compensate for expected losses. In that case, the realized profit will be lower than the expected profit, but the capital of the institution is not impaired. If unexpected losses are large, however, then they may exceed the profit margin and eat into the capital of the institution. The potential decline of a financial institution's capital is thus directly related to the potential for (large) unexpected losses.

The sub-prime crisis of 2007–2008 has presented many illustrations of the impact of unexpected losses on capital. During this crisis, many banks had to report large net losses that reduced the amount of available capital. As a result, several banks have sought new capital injections from outside investors to maintain their desired capital levels.

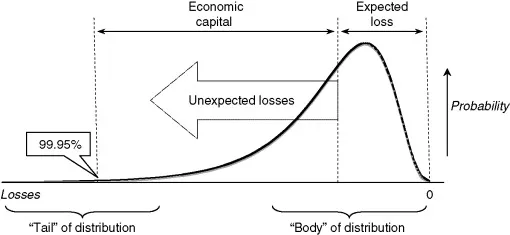

Graph 1.1 illustrates the concepts of expected loss, unexpected loss, and economic capital. The curved line depicts a loss distribution. On this loss distribution, we have indicated the amount of expected loss, as well as the amount of economic capital corresponding to a 99.95% confidence level. Unexpected losses are the losses that exceed the expected loss. For future reference, we also have indicated below the graph what constitutes the “body” of the distribution (i.e., the range of losses around the expected loss that have the highest probability of occurring) and the “tail” of the distribution (i.e., the area corresponding to large but unlikely losses).

Graph 1.1. Graphic depiction of expected loss, unexpected loss, and economic capital.

We note that the distinction between expected and unexpected losses is not directly applicable to all types of risk. For example, for trading activities we focus on potential changes in market values, and there is no natural interpretation of expected loss in this case. Market values are such that the expected return is sufficiently positive for market participants to invest in the assets. If the actual return falls short of the expected return, then the difference can be viewed as unexpected loss.

1.3. Conceptual Issues with Economic Capital

Economic capital has intuitive appeal, as it can be used as a direct estimate of the amount of capital that a financial institution should possess. There are, however, also drawbacks attached to its use as a risk measure. The first one relates to the fact that economic capital is an estimate of a very improbable event. As the confidence level that is used in the definition of economic capital is typically around 99.95%, we are trying to estimate a loss that will be exceeded in only 0.05% of all possible situations (or once every 2000 years if we measure economic capital over a one-year horizon and assume a constant universe). Being an estimate of such an improbable event, economic capital is unavoidably surrounded by uncertainty. In Section 1.3.1 we discuss the difference between risk and uncertainty, and how they impact the measurement of economic capital.

A second drawback relates to the mathematical properties of economic capital as a risk measure. Like the value-at-risk (VaR) measure, it violates one of the properties that have been postulated in the academic literature for coherent risk measures. In Section 1.3.2 we elaborate on this issue.

1.3.1. Risk Versus Uncertainty

Models that are used to calculate economic capital typically yield an estimate of the full probability distribution of potential gains and losses of a firm's assets and liabilities. We will often refer to this probability distribution as loss distribution, but it may also reflect potential gains. Estimating a loss distribution may not always be possible, however. Frank Knight already pointed out in 1921 that in many cases in economics and business it is very difficult if not impossible to know the loss distribution. He refers to risk when the probability distribution of events is known (measurable), and to uncertainty when this probability distribution is not known (immeasurable).[3]

An example of a situation in which we face risk is the throw of a fair die. All possible outcomes are known as well as their likelihood of occurrence (i.e., 1/6 for each number). To know the likelihood or probability that a certain number is thrown becomes complicated if we were told that the die is loaded. By rolling the die many times we can observe the fraction that each of the numbers turns up, and assume this is the true probability that we are looking for. However, even with a fair die the same number can be thrown many times in a row. Thus, if we depend on observations to estimate the loss distribution it will take many observations to be confident about our estimates. The problem of estimating the probability that a certain number will be thrown is even greater if we do not know whether we roll the same die each time, or if we do not know how many sides the die has. In the first instance, each throw of the die could be unique and earlier experiences are of little relevance. In the second instance, we do not know the range of possible outcomes. We have now reached the realm of uncertainty.

Few problems in risk management are like rolling a fair die. Seldom are the probabilities of possible events known a priori. As a result, we have to rely on observations to estimate them. These estimates are complicated by the fact that in business and economics there is continuous change. For example, technical progress and innovation change products and production techniques. Human behavior and social change influence consumer preferences.

In a broader perspective, the philosopher Karl Popper has made the point that the course of history is strongly influenced by t...