- 569 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Freshwater Ecology: Concepts and Environmental Applications is a general text covering both basic and applied aspects of freshwater ecology and serves as an introduction to the study of lakes and streams. Issues of spatial and temporal scale, anthropogenic impacts, and application of current ecological concepts are covered along with ideas that are presented in more traditional limnological texts. Chapters on biodiversity, toxic chemicals, extreme and unusual habitats, and fisheries increase the breadth of material covered. The book includes an extensive glossary, questions for thought, worked examples of equations, and real-life problems.

- Broad coverage of groundwaters, streams, wetlands, and lakes

- Features basic scientific concepts and environmental applications throughout

- Includes many figures, sidebars of fascinating applications, and biographies of practicing aquatic ecologists

- Materials are presented to facilitate learning, including an extensive glossary, questions for thought, worked examples of equations, and real life problems

- Written at a level understandable to most undergraduate students, with explanations of complex contemporary concepts in freshwater ecology described to promote understanding

- Featuring small chapters that mainly stand alone, this book can be read in the order most suited to the specific application

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Freshwater Ecology by Walter K. Dodds,Walter Dodds in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sciences biologiques & Écologie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Why Study Continental Aquatic Systems?

Human Utilization of Water: Pressures on a Key Resource

What Is the Value of Water Quality?

Summary

Questions for Thought

FIGURE 1.1 Crater Lake, Oregon.

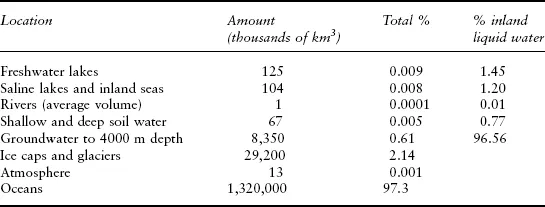

Although the majority of our planet is covered by water, only a very small proportion is associated with the continental areas on which humans are primarily confined (Table 1.1). Of the water associated with continents, a large amount (over 99%) is in the form of groundwater or ice and is difficult for humans to use. Human interactions with water most often involve fresh streams, rivers, marshes, lakes, and shallow groundwaters; thus, we rely heavily on a relatively rare commodity. As is true of all organisms, our very existence depends on this water; we need an abundance of fresh water to live.

TABLE 1.1

Locations and Amounts of Water on the Eartha

aData from Todd (1970).

Why study the ecology of continental waters? To the academic, the answer is easy: because it is fascinating and one enjoys learning for its own sake. Thus, the field of limnology1 (the study of lakes and streams) has developed. The study of limnology has a long history of academic rigor and broad interdisciplinary synthesis (Hutchinson, 1957, 1967, 1975, 1993; Wetzel, 2001). One of the truly exciting aspects of limnology is the integration of geological, chemical, physical, and biological interactions that define aquatic systems. No limnologist exemplifies the use of such academic synthesis better than G. E. Hutchinson (Biography 1.1); he did more to define modern limnology than any other individual. Numerous other exciting scientific advances have been made by aquatic ecologists, including the refinement of the concept of an ecosystem, ecological methods for approaching control of disease, methods to assess and remediate water pollution, ways to manage fisheries, restoration of freshwater habitats, understanding of the killer lakes of Africa, and conservation of unique organisms. Each of these will be covered in this text. I hope to transmit the excitement and appreciation of nature that comes from studying aquatic ecology.

Further justification for study may be necessary for those who insist on more concrete benefits from an academic discipline or are interested in preserving water quality and aquatic ecosystems in the broader political context. There is a need to place a value on water resources and the ecosystems that maintain their integrity and to understand how the ecology of aquatic ecosystems affects this value. Water is unique, has no substitute, and thus is extremely valuable. A possible first step toward placing a value on a resource is documenting human dependence on it and how much is available for human use.

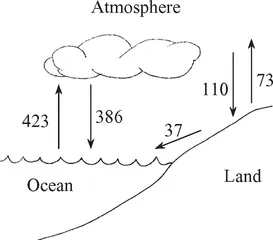

Humankind would rapidly use all the water on the continents were it not replenished by atmospheric input of precipitation. Hydrologic fluxes, or movements of water through the global hydrologic cycle, are central to understanding water availability. Much uncertainty surrounds some aspects of these fluxes. Given the difficulty that forecasters have predicting the weather over even a short time period, it is easy to understand why estimates of global change and the local and global effects on water budgets are beset with major uncertainties (Mearns et al., 1990; Mulholland and Sale, 1998). We are able to account moderately well for evaporation of water into the atmosphere, precipitation, and runoff from land to oceans. This accounting is accomplished with networks of precipitation gauges, measurements of river discharge, and sophisticated methods for estimating groundwater flow and recharge.

The global water budget is the estimated amount of water movement (fluxes) between compartments (the amount of water that occurs in each area or form) throughout the globe (Fig. 1.2). This hydrologic cycle will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 4 but is presented here briefly to allow for discussion of water available for human use. The total runoff from land to oceans via rivers has been reported as 22,100, 30,000, and 35,000 km3 per year by Leopold (1994), Todd (1970), and Berner and Berner (1987), respectively. These estimates vary because of uncertainty in gauging large rivers in remote regions. Next, I discuss demands on this potential upper limit of sustainable water supply.

FIGURE 1.2 Fluxes (movements among different compartments) in the global hydrologic budget (in thousands of km3 per year; data from Berner and Berner, 1987).

HUMAN UTILIZATION OF WATER: PRESSURES ON A KEY RESOURCE

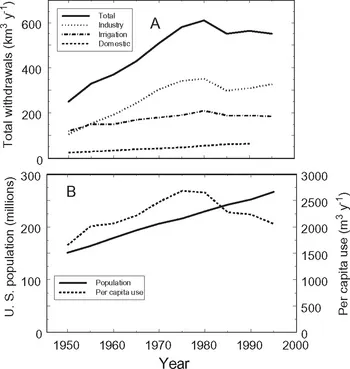

People in developed countries generally are not aware of the quantity of water that is necessary to sustain their standard of living. In North America particularly, high-quality water often is used for such luxuries as filling swimming pools and watering lawns. Perhaps people notice that their water bills increase in the summer months. Publicized concern over conservation may translate, at best, into people turning off the tap while brushing their teeth or using low-flow showerheads or low-flush toilets. Few understand the massive demands for water by industry, agriculture, and power generation that their lifestyle requires (Fig. 1.3).

FIGURE 1.3 Estimated uses of water (A), total population and per capita water use (B) in the United States from 1950 to 1990 [after Gleick (1993) and Solley et al. (1983)]. Note that industrial and irrigation uses o...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- AQUATIC ECOLOGY Series

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1: Why Study Continental Aquatic Systems?

- Chapter 2: Properties of Water

- Chapter 3: Movement of Light, Heat, and Chemicals in Water

- Chapter 4: Hydrology and Physiography of Groundwater and Wetland Habitats

- Chapter 5: Physiography of Flowing Water

- Chapter 6: Physiography of Lakes and Reservoirs

- Chapter 7: Types of Aquatic Organisms

- Chapter 8: Microbes and Plants

- Chapter 9: Animals

- Chapter 10: Biodiversity of Freshwaters

- Chapter 11: Aquatic Chemistry Controlling Nutrient Cycling: Redox and O2

- Chapter 12: Carbon

- Chapter 13: Nitrogen, Sulfur, Phosphorus, and Other Nutrients

- Chapter 14: Effects of Toxic Chemicals and Other Pollutants on Aquatic Ecosystems

- Chapter 15: Unusual or Extreme Habitats

- Chapter 16: Nutrient Use and Remineralization

- Chapter 17: Trophic State and Eutrophication

- Chapter 18: Behavior and Interactions among Microorganisms and Invertebrates

- Chapter 19: Predation and Food Webs

- Chapter 20: Nonpredatory Interspecific Interactions among Plants and Animals in Freshwater Communities

- Chapter 21: Fish Ecology and Fisheries

- Chapter 22: Freshwater Ecosystems

- Chapter 23: Conclusions

- Experimental Design in Aquatic Ecology

- Glossary

- References

- Index