eBook - ePub

Urban Disasters and Resilience in Asia

- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Urban Disasters and Resilience in Asia

About this book

Urban Disasters and Resilience in Asia presents the latest information on the intensity and frequency of disasters. Specifically, the fact that, in urban areas, more than 50% of the world's population is living on just 2% of the land surface, with most of these cities located in Asia and developing countries that have high vulnerability and intensification.

The book offers an in-depth and multidisciplinary approach to reducing the impact of disasters by examining specific evidence from events in these areas that can be used to develop best practices and increase urban resilience worldwide.

As urban resilience is largely a function of resilient and resourceful citizens, building cities which are more resilient internally and externally can lead to more productive economic returns. In an era of rapid urbanization and increasing disaster risks and vulnerabilities in Asian cities, Urban Disasters and Resilience in Asia is an invaluable tool for policy makers, researchers, and practitioners working in both public and private sectors.

- Explores a broad range of aspects of disaster and urban resiliency, including environmental, economic, architectural, and engineering factors

- Bridges the gap between urban resilience and rural areas and community building

- Provides evidence-based data that can lead to improved disaster resiliency in urban Asia

- Focuses on Asian cities, some of the most densely populated areas on the planet, where disasters are particularly devastating

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Urban Disasters and Resilience in Asia by Rajib Shaw,Atta-ur-Rahman,Akhilesh Surjan,Gulsan Ara Parvin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Local & Regional Planning Public Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Urban Disasters and Approaches to Resilience

Atta-ur -Rahman1, Rajib Shaw2, Akhilesh Surjan3, and Gulsan Ara Parvin4 1Associate Professor, Institute of Geography, Urban and Regional Planning, University of Peshawar, Peshawar, Pakistan 2Professor, Graduate School of Global Environmental Studies, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan 3Associate Professor, Faculty of Engineering, Health, Science and the Environment, Charles Darwin University, Darwin, Australia 4Researcher, Graduate School of Global Environmental Studies, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan

Abstract

Globally, the intensity and frequency of disasters are escalating and urban areas, where half of the world population lives, have been exposed to numerous disasters. Extreme events have hit urban areas in both developing and developed locations, but cities in the developing world have high vulnerability and low resilience. In the past, numerous cities were damaged by natural and human-induced disasters, with thousands of inhabitants either buried under debris or washed away by gushing water. Such disasters had impacted residential activities and put unprecedented impacts on city budgets because urban centers are the hub of industrial and commercial activities. Whenever a disaster hits an urban area, it creates widespread damage, and redirects budget allocation from development to emergency response. Currently, of 20 megacities in the world, 13 are in Asia, predominantly in the developing world. Cities in developing world are growing at an alarming rate, and as a consequence increases its vulnerability to numerous disasters. During the same period, the total population of Karachi, Pakistan, has grown by 80%, a remarkable increase. In these cities, over 37% of residents are living in slums and squatter settlements. As a consequence, the intensity and occurrences of urban disasters has increased, and authorities have been hard-pressed to cope with and build urban resilience to such events. The analysis in this chapter reveals that urban resilience is largely a reflection of resilient and resourceful citizens. The strong and committed involvement of citizens at the grass-roots level may result in cities that can withstand and react well to disasters.

Keywords

Urban resilience; Risk reduction; megacities; coastal hazards1.1. Introduction

More than half of the world population is now living in urban areas (UN, 2014). The urban population is increasing at a rapid rate, and it is projected that by the year 2030, 65% of the world’s population will be living in cities, mostly in the developing world (Sharma et al., 2011). Most of the top 20 cities in the world are in Asia, mainly located in the developing world. The data reveals that in the developing world, urban populations are increasing at a rapid pace that poses a series of threats to them. It has been estimated that in Asia, over 40% of its urban dwellers are living in slums and squatter settlements. Large cities are particularly vulnerable to a wide variety of hazards, with the majority of these populations living in high- to moderate-risk zones.

The so-called super cities, including Tokyo, Delhi, Shanghai, Dhaka, Mumbai, Karachi, Manila, Jakarta, Bangkok, and Calcutta, have experienced serious incidents of flooding, cyclone surges, and earthquakes in the past decade (Douglass, 2013). Meanwhile, several other Asian cities have faced heat waves, droughts, urban flooding, and intense rainfall. The effects of such incidents have been intensified by climate change. Cities are the hub of educational and cultural innovation and provide industrial, commercial, and infrastructure services (Shaw et al., 2009). Such links have positive implications to accelerate both the economic and political situations. Cities are certainly strong, but they are also vulnerable to wide range of disasters. This is why the urban authorities are called upon to develop city disaster risk reduction (DRR) plan(s) to cope, adapt to, or withstand shock, stress, and disturbances with minimum human casualties and damage (Rahman & Shaw 2015).

The continent of Asia is where the world’s least-urbanized countries are located. In Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Bangladesh, Vietnam, Nepal, India, Thailand, and Laos, less than 30% of the population lives in urban areas (UN, 2014). Singapore, Hong Kong, Qatar, Kuwait, Israel, South Korea, and Japan are among the most urbanized countries, with over 90% of the total population residing in cities. As a whole, the urban population in Asia is rapidly increasing compared to other continents. In Asia, in terms of degree of urbanization, 27 countries have more than 50% of their population living in urban areas. Of the top 20 megacities in the world, 13 are in Asia—namely, Tokyo, Delhi, Shanghai, Mumbai, Beijing, Osaka, Dhaka, Karachi, Calcutta, Istanbul, Chongqing, Manila, and Guangzhou, with populations of over 10 million (UN, 2014). Out of these cities, four are in China, three in India, two in Japan, and one each from Bangladesh, Pakistan, Turkey, and the Philippines. It is urban centers that accelerate the economic growth rate of high-income countries (i.e., Japan, South Korea, China, and Singapore), middle-income countries (i.e., Azerbaijan, India, Iran, and Pakistan) and low-income nations (i.e., Bangladesh, Cambodia, and Kyrgyzstan) (UNHABITAT, 2010).

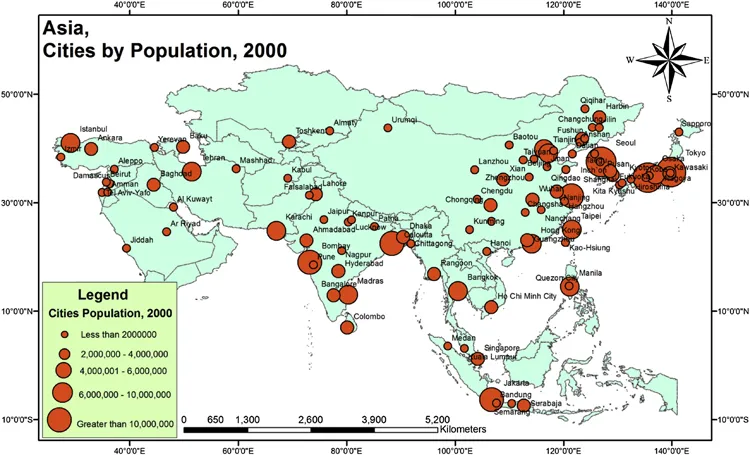

Figure 1.1 depicts the spatial distribution of the major urban centers in Asia in the year 2000. These cities are growing at an alarming rate, and between 2000–2010, cities in the developing world accounted for a two-thirds increase. During the same period, the population of Karachi, Pakistan, has grown remarkably, by 80%. In these cities, over 37% of urban citizens are living in slums and squatter developments. As a consequence, the intensity and occurrences of urban disasters has increased, and as a result the urban authorities have been hard-pressed to cope with and build urban resilience to these events. The analysis presented here shows that urban resilience is largely a function of resilient and resourceful citizens. The strong and committed involvement of citizens at the grass-roots level may lead to cities that can withstand and react well to disasters.

In the scientific research that is currently available, city resilience is considered as the capability of an established system to cope with and withstand the impact of a major disaster and recover quickly to normal city functioning. However, resilience largely varies from city to city and study to study, depending on the use and application of resilience methods. Similarly, vulnerability and exposure to such events also vary from city to city. Some cities are extremely vulnerable to coastal hazards, like Mumbai, Shanghai, Karachi, Chennai, Chittagong, Yangon, Ho Chi Minh City, Osaka, Singapore, and Semarang. The urban agglomerations in the Bohai Bay area (China), the Ganges-Brahmaputra deltaic region (Bangladesh), the Indus river delta (Pakistan), the Yangtze River delta (China) and the Pearl River delta region (China) are exposed to various coastal hazards. Some Asian cities are exposed to river flooding, like Dhaka, Delhi, Bangkok, Lahore, and Bandung. Several cities in India, the Philippines, Vietnam, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Myanmar, and China are frequently exposed to violent storms. Earthquakes are another type of devastating event, to which many cities in Japan, Indonesia, China, India, Pakistan, Iran, Bangladesh, Vietnam, and Thailand are comparatively more vulnerable.

It has been observed that developing cities generally spend only a small fraction of their budgets on disaster preparedness. Such limited investment in urban resilience can lead to massive damage after catastrophic events occur. Experience has shown that even a small investment in urban risk reduction is much more effective than picking up the pieces after a disaster (Rahman & Shaw, 2015). As cities are the hubs of commercial, industrial, and social activities, they contain large numbers of people in zones of great population density. They also act as engines for national economic growth and prosperity. It is cities that empower societies, and hence it is important to give them the attention they need in order to withstand disastrous events. The resilient capability of a city varies from location to location, and for this reason, increasing resilience is mainly a function of a city’s resilient and resourceful citizens. The committed and effective participation of city dwellers at the community level, and effectively addressing both internal and external negative factors, may yield productive and resilient cities.

Figure 1.1 Distribution of Asian cities, 2000.

1.2. Resilience in a Global Context

An earthquake occurring in the Indian Ocean in 2004, followed soon after by a tsunami, was a turning point in the history of global disaster risk management systems. After the Indian Ocean tsunami, the United Nations World Conference on Disaster Reduction (UNWCDR) was held on January 18–22, 2005, in Kobe, Japan. The UNWCDR provided a platform to bring together the scientific community, government stakeholders, and practitioners under a single but comprehensive agenda of reducing disaster vulnerabilities. The Hyogo Framework for Action: Building the Resilience of Nations and Communities to Disaster (HFA 2005–2015) was the outcome of this conference, which insisted that nations explicitly work on five priority areas (GoP, 2012).

HFA 2005–2015 is the agreed structure for making the world safer from extreme events and enhancing community resilience against disasters. In this agreement, 168 UN member-states decided on five action priorities, and a 10-year plan was set up to achieve a sizable lessening of disaster impacts on human lives and economic, social, and environmental assets of communities and nations.

Overall, the HFA has provided critical guidance in efforts to reduce disaster risk and contributed toward the achievement of the UN’s Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). The HFA priorities included ensuring that DRR is a national and a local priority with a strong institutional basis for its implementation; identifying, assessing, and monitoring disaster risks and enhancing early-warning systems; using knowledge, innovations, and education to build a culture of safety and resilience at all levels; reducing the underlying risk factors; and strengthening disaster preparedness for effective response at all levels (Queensland Government, 2014).

During the third United Nations World Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction, held in Sendai, Japan, from March 14–18, 2015, it was stated that 10 years after the adoption of the HFA, disasters continue to undermine efforts to achieve sustainable development in the developing world. Because of this, an HFA 2015-2030 agreement was reached with the aim of achieving, in the next 15 years, a substantial reduction of disaster risk and damage to lives, livelihoods, and health and the economic, physical, social, cultural, and environmental assets of people, businesses, communities, and countries as a whole. This will require strong political commitment and involvement in each country at all levels. Governments throughout the world are fully dedicated to enhancing communities’ capacity to handle disasters and building nations and community resilience against extreme events. Almost all UN member states have taken legislative and constitutional actions to establish disaster management agencies to mitigate, prepare for, prevent, and effectively respond to disasters and recover from emergency situations. In Asia, almost all the UN member states have approved legislation to establish disaster management authorities.

The Queensland Government, 2014 defined resilience as the capacity to prepare for, withstand, respond to, and recover from disasters. From this perspective, the basic idea is to build cities that are stronger and more resilient. UNISDR (2009) defined resilience as the ability of a system, community, or society to absorb, resist, accommodate to, and recover from disaster impacts in a timely and efficient manner, including through the restoration of its essential basic functions and structures. The condition of resilience has strengthened with time, which enhances the ability of many cities to minimize the effects of disasters in the future.

1.3. Impact of Disasters and Extent of Resilience

Of the 10 most damaging natural disasters throughout the world in 2013, 8 were reported in Asia (Caulderwood, 2014). The Philippines, China, and Vietnam suffered the most from Typhoon Haiyan in November 2013. Similarly, India, Nepal, and Pakistan were hit by flooding, which resulted in 7194 deaths, while an earthquake in Pakistan killed 825 people in September. In 2013, the most economically expensive disasters were that of flooding in central Europe, which cost $22 billion; an earthquake that occurred in Sichuan province, China, on April 20, which cost $14 billion; Super Typhoon Haiyan, which cost $13 billion; Typhoon Fitow in October in China and Japan, which cost $10 billion;droughts in China, which cost $10 billion; a series of droughts in Brazil, which cost $8 billion;flooding in Alberta, Canada, in July, which cost $5.2 billion; floods in north China in August–September, which cost $5 billion; another flood in southwest China, which cost $4.5 billion; and Hurricane Manuel in Mexico, which cost $4.2 billion(Caulderwood, 2014).

Disastrous events have occurred in both developing and developed nations, but developing nations are more vulnerable and experience such incidents more intensely (Rahman & Shaw, 2015). In the past decade, numerous cities have been affected by natural and human-induced disasters, where thousands of inhabitants either buried under debris or swept away by gushing water. Eventually, such urban disasters have extraordinary impacts on city budgets (Rahman & Shaw, 2015). Whenever any extreme event strikes an urban center, it seriously affects the residents in terms of both human casualties and physical and economic losses. Historically, urban centers are designed to empower the societies that contain them, as cities are the hubs of commercial and industrial activities. When disaster strikes, this pr...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- List of Contributors

- About the Editors

- Preface

- About the Book

- 1. Urban Disasters and Approaches to Resilience

- 2. Urban Risk, City Government, and Resilience

- 3. Cities, Vulnerability, and Climate Change

- 4. Resilient Homes Make Cities Resilient

- 5. Urban Regulation and Enforcement: A Challenge

- 6. Expanding Coastal Cities: An Increasing Risk

- 7. Impact of Urban Expansion on Farmlands: A Silent Disaster

- 8. Enhancing City Resilience Through Urban-Rural Linkages

- 9. Urban Disaster Risk Reduction in Vietnam: Gaps, Challenges, and Approaches

- 10. Urban Disasters and Microfinancing

- 11. Urban Food Security in Asia: A Growing Threat

- 12. Identifying Priorities of Asian Small- and Medium-Scale Enterprises for Building Disaster Resilience

- 13. Urban Disasters and Risk Communication Through Youth Organizations in the Philippines

- 14. Flood Risk Reduction Approaches in Dhaka, Bangladesh

- 15. Postdisaster Urban Recovery: 20 Years of Recovery of Kobe

- 16. Community Resilience Approach for Prioritizing Infrastructure Development in Urban Areas

- 17. Vernacular Built Environments in India: An Indigenous Approach for Resilience

- 18. Building Community Resiliency: Linkages Between Individual, Community, and Local Government in the Urban Context

- 19. Climate Migration and Urban Changes in Bangladesh

- 20. Water Stress in the Megacity of Kolkata, India, and Its Implications for Urban Resilience

- Index