Publisher Summary

The normal function of the immune system is to provide protection against invasion by pathogens. It is, unfortunately, also the source of less welcome events, such as graft rejection and autoimmune diseases, in which the system reacts against normal body constituents. An immune response, whether it be beneficial or harmful, is a multi-layered phenomenon. There are two forms of immunities present in a living body—innate immunity that is present through the course of the being’s lifetime and acquired immunity that stems from adaptations by the body to foreign stimulus with effector functions working in response to that particular stimulus. Adaptation shows itself in two characteristics, specificity and memory, that combine to give the system its efficiency. The three defining characteristics of the acquired response—specificity, memory, and self/nonself discrimination—reflect the properties and activities of lymphocytes. These cells are directly responsible for the acquired immune response, although in many instances the response also requires the involvement of cells of the monocyte/macrophage lineage.

I THE ORGANIZATION OF IMMUNE PROTECTION

The normal function of the immune system is to provide protection against invasion by pathogens. It is, unfortunately, also the source of less welcome events, such as graft rejection and autoimmune diseases, in which the system reacts against normal body constituents. An immune response, whether it be beneficial or harmful, is a multi-layered phenomenon. The purpose of this chapter is twofold. The first is to provide an introductory description of the various layers, in conjunction with an indication of some of the interactions that occur both between the layers and within them. The second is a more detailed consideration of those aspects of the system that are of most interest and importance to scientists who wish simply to use immunological techniques, particularly antibodies, in their research. The emphasis is on the genetic, cellular, and molecular events that give rise to the production of antibodies, rather than on immunochemistry per se. Nonimmunologists frequently complain that the language and terminology used in immunology present major barriers to an appreciation of the system, obscuring rather than clarifying. Although this chapter is in no sense a replacement for a comprehensive dictionary, it may make some aspects of the immune system more understandable.

II INNATE AND ACQUIRED IMMUNITY

The first broad separation is the discrimination between innate and acquired immunity. Innate immunity is, as its name suggests, present at birth and persists throughout life. It represents the first line of defense against insult (the word “insult” is used broadly in immunology and refers to invasion by pathogenic microorganisms, parasites, and, in some instances, tumors) and is composed of a number of physical, cellular, and chemical barriers. Skin and mucous membranes physically impede invasion. Chemical barriers include gastric pH, enzymes such as lysozyme in tears and saliva, and other biologically active molecules such as the interferons and the proteins of the complement system. Cells, such as polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) and natural killers (NKs) are also integral components of this aspect of protection. Thus at least three layers of protection exist in innate immunity. Although each is mechanistically quite different in the way in which protection is effected, there are characteristics that all layers have in common. Each layer is either continuously present, or very rapid in response to insult. The layers show no specificity vis a vis the insult: they are incapable of discriminating between different pathogens. Also, they show no memory of prior insults: neither the quality nor the quantity of innate immunity is increased by a second exposure to the same pathogen. Acquired immunity differs from innate immunity in each of these characteristics. Table I shows a comparison between innate and acquired immunity. The elements of innate immunity provide a significant degree of protection; the severity of immune deficiency syndromes that reflect a lack of individual components of this system provides ample evidence of its importance.

TABLE I

Differences between Innate and Acquired Immunity

| Property | Innate immunity | Acquired immunity |

| Components | Physical barriers, e.g., skin; chemical barriers, e.g., lysozyme, interferons; cellular components, e.g., NK cells | Lymphocytes and accessory cells |

| Specificity | None | Specific for insult or pathogen |

| Presence at birth | Yes | Some elements; others develop postnatally |

| Effect of exposure to insult | None; no memory generated | Effector function and memory elicited |

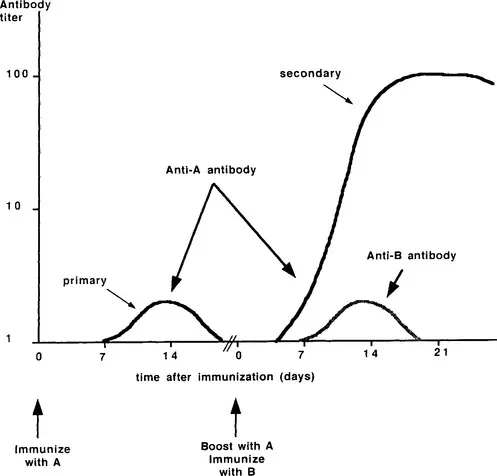

In contrast, acquired immunity is adaptive, since it responds to the particular insult with effector functions that act only on that insult. Adaptation shows itself in two characteristics, specificity and memory, which combine to give the system its efficiency. Figure 1 shows the time courses and magnitudes of (antibody) responses to two immunologically unrelated substances, designated A and B. The figure illustrates the difference in response subsequent to first (primary) and second (secondary) exposure to a foreign substance; this behavior reflects immunological memory. Specificity is the ability to discriminate between different insults; in the figure, the primary immunization with A elicits antibodies that recognize A only; the memory that this response generates is specific for A. Specificity may be maintained even when the substances are closely related biologically and chemically. One of the best known examples of the system’s ability to distinguish subtle differences is the human ABO blood group system (Landsteiner, 1946). Perhaps an even more striking example of the level of discrimination possible is that antibody populations may be identified that are capable of discriminating between closely related nitrophenyl groups (Little and Eisen, 1969). Immunological memory is very much like that observed in the functioning of the nervous system: the cells have the ability to recognize, and respond to, the second (or third, and so on) exposure to a given insult in a way that is both quantitatively and qualitatively different from the response to the first, or primary, exposure. Moreover, memory is itself specific because the enhanced response subsequent to re-exposure is directed only toward the foreign substance used for initial immunization.

FIGURE 1 Kinetic and quantitative differences between primary and secondary humoral (antibody) responses. The primary response to immunization with A shows a lag period of ~7 days, followed by a logarithmic increase, a relatively low plateau titer, and a rapid decay. In contrast, secondary immunization with A gives rise to a response with a shorter lag period, a steeper logarithmic increase reaching a significantly higher plateau (note the logarithmic scale of the ordinate), and a slow decay phase. The difference between primary and secondary responses reflects immunological memory, which has been generated as a consequence of primary immunization, but which requires rechallenge to be expressed. The secondary immunization with A is accompanied by primary immunization with an immunologically distinct substance, B. The indicated response to B is characteristic of a primary response, indicating that memory itself is specific.

The acquired immune response shows an additional characteristic that is of considerable significance for homeostasis, the ability to discriminate between self and nonself. The phenomenon was first shown in the 19th century by Paul Ehrlich (1900), who gave it the name “Horror Autotoxicus.” In its simplest terms, the observation is that, although vertebrates may be immunized with foreign (i.e., nonself) material and be shown to mount an immune response, spontaneous responses to the animal’s own molecules leading to autoimmune disease (i.e., anti-self) are rare. The process by which recognition of self is minimized is referred to as self-tolerance. Self-tolerance is not simply a failure to recognize self components, but is an active process involving the regulation of lymphocyte survival and function (see subsequent text and Figures 7 and 8; Nossal, 1994).

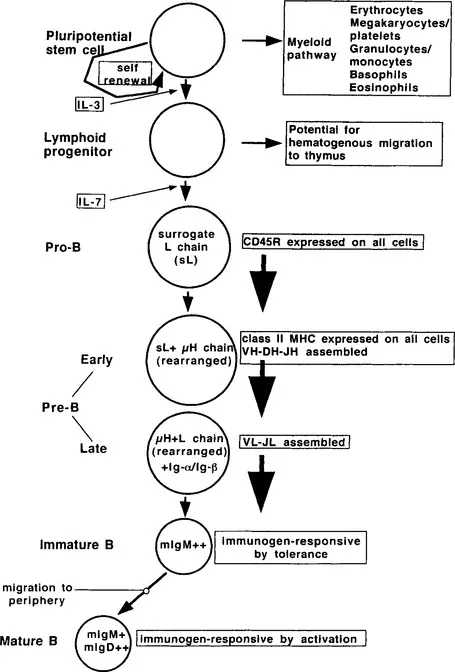

FIGURE 7 Developmental sequence of B cells. B cells are derived from the pluripotential stem cell, which has self-renewing capacity and is also able to give rise to all elements of the hemopoietic system. Interleukin-3 (IL-3) is required for development of the lymphoid progenitor, a cell that is irreversibly committed to the lymphocytic pathway. This cell can give rise to both B and T lymphocytes. The latter require migration from bone marrow to thymus for development. Pro-B cell development is driven by IL-7. Pro-B cells express CD45 and surrogate light chain and are the first unambiguous step in the B cell pathway. Pre-B cells are the stage at which class II MHC becomes expressed and the Ig loci undergo the rearrangements that result in the expression of variable region domains. The heavy chain locus rearranges prior to the light chain. Immature B cells express mIgM and the signal-transducing complex of Ig-α and Ig-β. As such, these are the first cells in the pathway to be responsive to external immunogen. However, exposure to immunogen results in tolerization. The final step is the mature B cell. This is recognized by the co-expression of mIgM and mIgD. These cells migrate to the...