eBook - ePub

Postharvest Biology and Technology of Tropical and Subtropical Fruits

Mangosteen to White Sapote

- 536 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Postharvest Biology and Technology of Tropical and Subtropical Fruits

Mangosteen to White Sapote

About this book

While products such as bananas, pineapples, kiwifruit and citrus have long been available to consumers in temperate zones, new fruits such as lychee, longan, carambola, and mangosteen are now also entering the market. Confirmation of the health benefits of tropical and subtropical fruit may also promote consumption further. Tropical and subtropical fruits are particularly vulnerable to postharvest losses, and are also transported long distances for sale. Therefore maximising their quality postharvest is essential and there have been many recent advances in this area. Many tropical fruits are processed further into purees, juices and other value-added products, so quality optimisation of processed products is also important. The books cover current state-of-the-art and emerging post-harvest and processing technologies. Volume 1 contains chapters on particular production stages and issues, whereas Volumes 2, 3 and 4 contain chapters focused on particular fruit.Chapters in Volume 4 review the factors affecting the quality of different tropical and subtropical fruits from mangosteen to white sapote. Important issues relevant to each product are discussed, including means of maintaining quality and minimising losses postharvest, recommended storage and transport conditions and processing methods, among other topics.With its distinguished editor and international team of contributors, Volume 4 of Postharvest biology and technology of tropical and subtropical fruits, along with the other volumes in the collection, are essential references both for professionals involved in the postharvest handling and processing of tropical and subtropical fruits and for academics and researchers working in the area.

- Along with the other volumes in the collection, Volume 4 is an essential reference for professionals involved in the postharvest handling and processing of tropical and subtropical fruits and for academics and researchers working in the area

- Reviews factors affecting the quality of different tropical and subtropical fruits, concentrating on postharvest biology and technology

- Important issues relevant to each particular fruit are discussed, such as postharvest physiology, preharvest factors affecting postharvest quality and pests and diseases

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Postharvest Biology and Technology of Tropical and Subtropical Fruits by Elhadi M. Yahia in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technologie et ingénierie & Agrobusiness. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.)

S. Ketsa, Kasetsart University Thailand

R.E. Paull, University of Hawaii at ManoaUSA

Abstract:

Mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) is one ofthe most admired tropical fruit and known widely as the Queen of Fruits for its beautiful purple blue pericarp and delicious flavor. The edible aril is white, soft and juicy with sweet pleasant taste. Mangosteen is a climacteric fruit that undergoes rapid postharvest changes resulting in a short shelf life at ambient temperature. Physiological disorders induced by preharvest and postharvest factors have a major impact on the appearance and eating quality. In addition to fresh consumption, the aril is processed into other products. The fruit pericarp also contains many chemical compounds that have possible medicinal value.

Key words

mangosteen

postharvest change

physiological disorder

postharvest handling quality

1.1 Introduction

1.1.1 Origin, botany, morphology and structure

The mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) originated in Southeast Asia and is a member of the family Clusiaceae. In earlier works, the genus had been placed in the Guttiferae. The genus name Garcinia was given by Linnaeus in honor of French naturalist Laurent Garcin for his work as a botanist in the eighteenth century. Laurent Garcin with others had made one of the most detailed descriptions of the fruit. Although the word ‘mango’ occurs in the word ‘mangosteen’ there is no botanical relationship at the genus or family levels. The name mangosteen is thought to have been derived from Malay or Javanese.

According to Verheij (1991: 443):

The mangosteen as a fresh fruit is in great demand in its native range and is savored by all who find its subtle flavors a refreshing balance of sweet and sour. It should be pointed out that Asians consider many foods to be either ‘cooling’ such as the mangosteen or ‘heating’ such as the durian depending on whether they possess elements that reflect yin and yang. This duality is commonly used to help describe balance in many aspects of life in general and food in particular throughout Asia.

Morton (1987: 505) describes the mangosteen as follows:

The mangosteen is a very slow-growing, erect tree with a pyramidal crown. The tree can attain 6 to 25 m (20 to 82 ft) and has dark-brown or nearly black, flaking bark, the inner bark containing much yellow, gummy, bitter latex. This evergreen has opposite, short-stalked leaves that are ovate-oblong or elliptic, leathery and thick, dark-green, slightly glossy above and yellowish-green and dull beneath. New leaves have a rosy hue. The mature leaves are 9 to 25 cm long (3 1/2 to 10 in) and 4.5 to 10 cm wide (1 3/4 to 4 in) with conspicuous, pale midribs. Female flowers are 4 to 5 cm wide (1 1/2 to 2 in). The flowers are borne singly or in pairs at the tips of young branchlets; their fleshy petals may be yellowish-green, edged with red or mostly red, and the petals are quickly shed.

No male flowers or trees have been described, though it is said to be dioecious. Mangosteen is only known as a female cultivated plant. Based on morphological characters, mangosteen may be a sterile allopolyploid hybrid (2n = 88 – 90) between two Garcinia spp.

Morton (1987: 505) further describes that:

the smooth round fruit, 3.4 to 7.5 cm in diameter (1 1/3 to 3 in), is capped by a prominent calyx at the stem end that has 4 to 8 triangular, flat remnants of the stigma in a rosette at the apex. When the fruit is mature and ripe, it is dark-purple to reddish-purple. The rind (pericarp) is 6 to 10 mm thick (1/4 to 3/8 in) and spongy and in cross-section is red outside and purplish-white on the inside. The pericarp has a bitter yellow latex, and a purple, staining juice. Inside the pericarp are 4 to 8 triangular segments of snow-white, juicy, soft edible flesh (aril) that clings to the seeds. The fruit may be seedless or have 1 to 5 fully developed seeds. The seeds are ovoid-oblong, somewhat flattened, 2.5 cm (1 in) long and 1.6 cm wide (5/8 in).

The edible aril is white, juicy, sweet and slightly-acid, with a pleasant flavor (Fu et al., 2007; Ji et al., 2007). It is similar in shape and size to a tangerine. The circle of wedge-shaped arils contains 4 to 8 segments, the larger of which contain the apomictic seeds that are unpalatable unless roasted. Fruit are harvested at various stages of ripeness, referred to as Stage 1 to Stage 6. During ripening, Hue angle and pericarp firmness decline significantly, while soluble solids contents (SSC) increases and titratable acidity (TA) decreases resulting in an increase of SSC: TA ratio, and better tasting fruit. Fruit harvested at Stage 1 and allowed to ripen to Stage 6 show no significant differences in sensory quality and fruit appearance to fruit harvested at Stage 6.

In the absence of fertilization, asexual ovary nucellus tissue development occurs that ensures fruit and aril growth. The asexual embryos develop from the nucellus tissue and these apomixic ‘seed’ are used in propagation. The ‘seed’ is a clone of the mother plant with little variation (Richards, 1990; Ramage et al., 2004), but the absence of true seed associated with sexual fertilization limits varietal development and selection. DNA and RNA marker analysis from material sourced globally has shown variation among the different mangosteen populations. The majority of the samples had essentially the same genetic make-up (genotype) but significant differences were found in same samples (Yapwattanaphun and Subhadrabandhu, 2004). This difference could be due to chance mutation or selection within the limited variation that is known to occur.

1.1.2 Worldwide importance

Mangosteen fruit is now grown worldwide and is being exported and marketed in more developed countries. Often it is advertised and marketed as a novel functional food and is sometimes called a ‘super fruit’. It is presumed to have a combination of

• appealing characteristics, such as taste, fragrance and visual qualities,

• nutrient richness,

• antioxidant strength, and

• potential impact for lowering risk of human diseases (Gross and Crown, 2007).

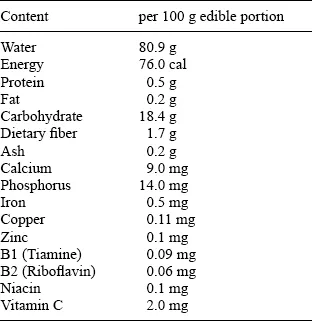

1.1.3 Nutritional value and health benefits

The aril, though having a pleasant taste and flavor, has a low nutrient content (Table 1.1). Recent research on antioxidant determination showed that plant foods with rich colors had high scores of oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC) whereas those that were white (without pigments) had low ORAC (Wu et al., 2004). Following this simple and subjective index, the white mangosteen aril should have a low ORAC, though no ORAC results have been reported for the aril to date. Some mangosteen juice products contain whole fruit purée or polyphenols extracted from the inedible pericarp (rind) as a formulation strategy to add phytochemical value. The resulting juice has a purple color and astringency derived from pericarp pigments. Xanthone extracts taken from the pericarp (Jung et al., 2006) and added to a juice could be beneficial (Anon, 2007). Apha-mangostin, a xanthone, can stimulate apoptosis in leukemia cells in vitro (Matsumoto et al., 2004). The preliminary nature of this research means that no definite conclusions can be drawn about possible health benefits for humans eating mangosteen.

Table 1.1

Nutritional values of mangosteen fruit (per 100 g edible portion).

Source: Anon. (2004). Fruits in Thailand. Department of Agricultural Extension, Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives, Bangkok, Thailand.

1.2 Fruit development and postharvest physiology

1.2.1 Fruit growth, development and maturation

At fruit set, fruit shape is almost spherical, with fruit length and width b...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Contributor contact details

- Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition

- Foreword

- Chapter 1: Mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.)

- Chapter 2: Melon (Cucumis melo L.)

- Chapter 3: Nance (Byrsonima crassifolia (L.) Kunth)

- Chapter 4: Noni (Morinda citrifolia L.)

- Chapter 5: Olive (Olea europaea L.)

- Chapter 6: Papaya (Carica papaya L.)

- Chapter 7: Passion fruit (Passiflora edulis Sim.)

- Chapter 8: Pecan (Carya illinoiensis (Wangenh.) K. Koch.)

- Chapter 9: Persimmon (Diospyros kaki L.)

- Chapter 10: Pineapple (Ananas comosus L. Merr.)

- Chapter 11: Pistachio (Pistacia vera L.)

- Chapter 12: Pitahaya (pitaya) (Hylocereus spp.)

- Chapter 13: Pitanga (Eugenia uniflora L.)

- Chapter 14: Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.)

- Chapter 15: Rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum L.)

- Chapter 16: Salak (Salacca zalacca (Gaertner) Voss)

- Chapter 17: Sapodilla (Manilkara achras (Mill) Fosb., syn Achras sapota L.)

- Chapter 18: Soursop (Annona muricata L.)

- Chapter 19: Star apple (Chrysophyllum cainito L.)

- Chapter 20: Sugar apple (Annona squamosa L.) and atemoya (A. cherimola Mill. × A. squamosa L.)

- Chapter 21: Tamarillo (Solanum betaceum (Cav.))

- Chapter 22: Tamarind (Tamarindus indica L.)

- Chapter 23: Wax apple (Syzygium samarangense (Blume) Merr. and L.M. Perry) and related species

- Chapter 24: White sapote (Casimiroa edulis Llave & Lex)

- Index