eBook - ePub

Bacterial Biogeochemistry

The Ecophysiology of Mineral Cycling

- 312 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Bacterial Biogeochemistry

The Ecophysiology of Mineral Cycling

About this book

Bacterial Biogeochemistry, Third Edition focuses on bacterial metabolism and its relevance to the environment, including the decomposition of soil, food chains, nitrogen fixation, assimilation and reduction of carbon nitrogen and sulfur, and microbial symbiosis. The scope of the new edition has broadened to provide a historical perspective, and covers in greater depth topics such as bioenergetic processes, characteristics of microbial communities, spatial heterogeneity, transport mechanisms, microbial biofilms, extreme environments and evolution of biogeochemical cycles.

- Provides up-to-date coverage with an enlarged scope, a new historical perspective, and coverage in greater depth of topics of special interest

- Covers interactions between microbial processes, atmospheric composition and the earth's greenhouse properties

- Completely rewritten to incorporate all the advances and discoveries of the last 20 years such as applications in the exploration for ore deposits and oil and in remediation of environmental pollution

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Bacterial Biogeochemistry by Tom Fenchel,Henry Blackburn,Gary M. King in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Environmental Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Bacterial Metabolism

1.1 General Considerations: Functional Properties of Bacteria

Bacteria are small: typical bacteria measure between 0.5 and 2 μm in diameter. A few are somewhat smaller, the so-called nanoarchaea, represented by Nanoarchaeum equitans, which is about 0.4 µm in diameter is an obligate symbiont of another, larger archaeum (Waters et al., 2008). Structures smaller than about 0.4 µm have been claimed to be bacteria, but in what is regarded as free-living forms, none of these have yet proven to be metabolically active organisms, nor have their fossils.

A few bacteria are considerably larger than 2 µm: some cyanobacterial cells exceed 5 μm and some sulfide oxidizing bacteria may reach a size of 20 μm or more (Thiovulum, Beggiatoa); Achromatium has been recorded to measure up to 0.1 mm, and Thiomargarita has a diameter of 0.75 mm (Schultz & Jørgensen, 2001). It would seem that there is a size-overlap with unicellular eukaryotes, the tiniest of which measure 2–3 μm, but most are five to 100 times larger. In contrast to small eukaryotes most of the volume of very large bacteria is constituted by a vacuole or by inclusions.

Most bacteria are unicellular, although some form colonies that are filamentous or otherwise shaped. Bacterial cells may be rod-shaped (rods), spherical (cocci), comma-shaped (vibrios) or helicoidal (spirilla), but other morphotypes occur as well. Some soil bacteria, in particular, form fungi-like mycelia (actinobacteria, myxobacteria), and myxobacteria have complex life cycles including the formation of sporangia. Bacteria almost always have a rigid cell wall surrounding the cell membrane. Exceptions include obligate intracellular parasites (e.g., Chlamydia) for which the protection against water stress provided by a cell wall is not necessary.

The two important characteristics of bacteria (small size, rigid cell walls) are necessary consequences of the absence of a cytoskeleton, a trait that characterizes eukaryotic cells. These traits explain two additionally important properties of bacteria. One is that bacteria can take up only low molecular weight compounds from their surroundings via the cell membrane and this uptake is brought about either by active (energy-requiring) transport or by facilitated diffusion. Bacteria that utilize polymers or particulate organics can do so only indirectly through extracellular hydrolysis of the substrate catalyzed by membrane-bound or excreted hydrolytic enzymes before the resulting low molecular weight molecules can be transported into the cells (see Chapter 3). Bacteria cannot bring particulate material or macromolecules into their cells; the capability of phagocytosis or pinocytosis is a privilege of eukaryotic cells. Bacterial transformation, which involves uptake of single stranded DNA by bacteria, represents an exception with evolutionary implications. Another consequence of the absence of a cytoskeleton is that all transport within the bacterial cell depends on molecular diffusion and this limits the maximum sizes that bacterial cells can attain. On the other hand, the small size of bacteria renders them extremely efficient in concentrating their substrates from very dilute solutions (see Chapter 2).

Finally, a consequence of small size – when comparing organisms spanning a large size spectrum – is a high “rate of living” or metabolic rate; that is, small organisms tend to have higher volume-specific metabolic rates and shorter generation times than do larger organisms. Roughly speaking, when comparing organisms of widely different sizes, specific growth rate constants and volume-specific metabolic rates are proportional to (volume)−1/4, notwithstanding that there may be variation in potential growth rates among species of similar size. Under optimal conditions many bacteria have generation times of only 15–30 minutes, with as little as ten minutes the fastest known. Generation times for a 100 μm long protozoan, a copepod and a small fish would be roughly eight hours, 10 days and one year, respectively.

Although the total biomass of bacteria may not be large relative to that of multi-cellular organisms in some habitats (especially terrestrial systems), the impact of bacteria in terms of matter transformations and energy flow may be much greater. For example, seawater typically contains around 106 bacteria per ml of water resulting in a volume fraction somewhat less than 10−6. This is comparable to the volume fraction made up by protozoa; however, the metabolic activity of the bacterial community may be roughly an order of magnitude higher than that of the protozoa.

Another property important for understanding the role of bacteria in nature is that they hold all records as “extremophiles”. Some bacteria live at temperatures exceeding 80°C or even up to the temperature of an autoclave, 121°C under hyperbaric pressure (extreme thermophiles). Others thrive in concentrated brine (extreme halophiles), at a pH<2 (acidophiles) or pH>10 (alkaliphiles), and some are tolerant to mM concentrations of toxic metal and metalloid ions such as As, Cu, Zn, amongst others (see Chapter 10). Other habitats not usually considered “extreme” in the senses above, exclude most multi-cellular organisms, and are inhabited almost entirely by bacteria in practice. Such habitats include anoxic, strongly sulfidic waters and sediments (which otherwise harbour only a few types of specialized protozoa) and some sediments rich in clay and silt with small pore sizes that preclude many larger organisms.

In contrast to aquatic systems and extreme environments in which bacteria are dominant, terrestrial systems (soils and the litter layer) often support communities of fungi that rival or exceed bacteria in biomass and activity. This is especially true for the primary decomposition of plant structural compounds (e.g., cellulose and lignocellulose), which fungi typically dominate. One reason for the more limited role of bacteria in terrestrial systems is that among all the possible types of physical and chemical constraints found in nature, bacteria seem to have only one absolute requirement for activity: liquid water. Many bacteria, especially soil isolates, produce desiccation-resistant structures, e.g., cysts and spores. However, metabolic activity and growth require water, and because of this requirement, growth and metabolic activity of “terrestrial bacteria” is confined to micrometer-thick aqueous films that cover mineral and detrital particles in soils, the surfaces of rocks, litter, and roots, stems and leaves of living plants.

Relative to bacteria, fungi can tolerate water stress to a much greater extent, and are not constrained to aqueous films. Indeed, fungal hyphae can ramify through gas-filled soil pores as well as cellulosic walls of plants, thus exploring the soil space and promoting plant polymer decomposition. In this respect, fungi are better adapted to life in soil and litter. The relation between fungi and bacteria is discussed in more detail in Chapter 5.

Yet another profoundly important reason for the pivotal role of bacteria in all ecosystems is their metabolic diversity. Some species of bacteria are very specialized with respect to their substrates and available metabolic pathways. But the metabolic repertoire of bacteria taken together far exceeds that known from eukaryotes. Examples of processes that are exclusively carried out by certain bacteria include methanogenesis, the oxidation of methane and other hydrocarbons, and nitrogen fixation. These and several others that are carried out exclusively by different kinds of bacteria are all key processes in the function of the biosphere.

Similarly, bacteria collectively have an astonishing capability to hydrolyze virtually all natural polymers as well as many “unusual” compounds such as secondary plant metabolites, compounds found in crude oil, and many xenobiotics. The degradation of polymers, which is a question of extracellular hydrolysis, is treated in Chapter 3. Here we proceed with a discussion on bacterial metabolic diversity.

1.2 Bacterial Metabolism

Bacteria, like all living organisms, are capable of increasing in size (growth) and dividing (reproduction). Bacterial activities are directed to this end, and this requires energy and a variety of substrates from the environment for the synthesis of cellular material. These two activities, i.e. obtaining energy and obtaining or synthesizing “building blocks” for growth are referred to as dissimilatory (energy or catabolic) metabolism and assimilatory (anabolic) metabolism, respectively.

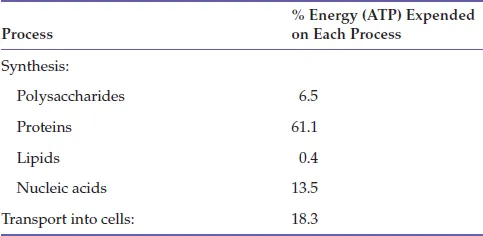

It is convenient to discuss these separately, and we do so in the following passages. However, the two types of metabolism are tightly coupled in the sense that microorganisms spend by far the most power they generate on growth due to the high energetic costs of macromolecule synthesis (DNA, RNA and proteins), and of transport of molecules in and out through the cell membrane (see Table 1.1).

Table 1.1. Bacterial Energy Budget for Cells Grown on Glucose (Based on Stouthamer 1973)

Under most normal growth conditions there is, therefore, an almost linear relation between the growth rate constant (measuring the balanced increase in biomass) and the rate of power generation. Furthermore, a particular substrate may serve both as an energy source and as a carbon source. Thus, a bacterium growing aerobically on glucose will use this substrate partly as a source of energy (oxidizing it to CO2) and partly as a source for cell material (largely without changing the oxidation level of the C atoms). In other cases, the energy source and the assimilated materials are different. This is trite in the case of phototrophs, but it also applies, for example, to sulfide-oxidizing bacteria, which must assimilate CO2 or some other material. Finally, the enzymes involved in assimilatory and dissimilatory metabolism may overlap with identical metabolic pathways serving as oxidative, catabolic pathways in some species or under some circumstances – running in reverse – as reductive anabolic pathways in other species or circumstances. For example, the citric acid (TCA) cycle is used in most respiratory organisms for the stepwise oxidation of acetate to CO2. However, in the phototrophic green sulfur bacteria (e.g., Chlorobium), the Aquificales, some Proteobacteria, and in some Archaea, the citric acid runs in reverse and is used as a synthetic, reductive pathway for the assimilation of CO2. In the former case it is an oxidative energy generating pathway, in the latter case it is a reductive energy requiring (ATP-consuming) pathway. In the purple non-sulfur bacteria (e.g., Rhodopseudomonas), the same electron transport system is used for both respiration and for photophosphorylation (Fig. 1.1). These and similar examples are of considerable interest in an evolutionary context because they illuminate the origin and evolution of metabolic pathways; they also show how a relatively small number of basic pathways can lead to a relatively large metabolic repertoire (see Chapter 11). Under all circumstances, it should be kept in mind that while the distinction between dissimilatory and assimilatory metabolism is meaningful in s...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter 1. Bacterial Metabolism

- Chapter 2. Transport Mechanisms

- Chapter 3. Degradation of Organic Polymers and Hydrocarbons

- Chapter 4. Comparison of Element Cycles

- Chapter 5. The Water Column

- Chapter 6. Biogeochemical Cycling in Soils

- Chapter 7. Aquatic Sediments

- Chapter 8. Microbial Biogeochemistry and Extreme Environments

- Chapter 9. Symbiotic Systems

- Chapter 10. Microbial Biogeochemical Cycling and the Atmosphere

- Chapter 11. Origins and Evolution of Biogeochemical Cycles

- APPENDIX 1. Thermodynamics and Calculation of Energy Yields of Metabolic Processes

- APPENDIX 2. Phylogeny and Function in Biogeochemical Cycles

- Index