![]()

PART I

Analytical Techniques

Chapter 1 Basics and Advances in Sampling and Sample Preparation

Chapter 2 Data Analysis and Chemometrics

Chapter 3 Near-Infrared, Mid-Infrared, and Raman Spectroscopy

Chapter 4 Nuclear Magnetic Resonance

Chapter 5 Low-Intensity Ultrasounds

Chapter 6 The Applications of Nanotechnology

Chapter 7 Microfluidic Devices

Chapter 8 Electronic Noses and Tongues

Chapter 9 Mass Spectrometry

Chapter 10 Liquid Chromatography

Chapter 11 Gas Chromatography

Chapter 12 Electrophoresis

Chapter 13 Molecular Techniques

![]()

Chapter 1

Basics and Advances in Sampling and Sample Preparation

L. Ramos

Department of Instrumental Analysis and Environmental Chemistry, IQOG-CSIC, Juan de la Cierva 3, Madrid, Spain

Outline

1.1. Introduction

1.2. Types of Samples and the Analytical Procedure

1.3. Trends in Sample Preparation for Food Analysis

1.4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

1.1 Introduction

The first problem faced when dealing with food science is probably the statement of the concept of food. A number of possible definitions for this concept can be found in the specialized literature. Some of them focus on its composition (typically, carbohydrates, fats, protein and water), others in the way used by humans to seek food items (which, in most cultures, has nowadays changed from hunting and gathering to farming, ranching, and fishing). In other cases, definitions focus on the nature of the matter itself and/or the expected benefices associated to its consumption. Finally, one should recognize that, above definitions, the concept food is also highly cultural dependent. Items considered food may be sourced from water, minerals, plants, animals, or other categories such as fungus, fermented, elaborated, and processed products. Taking into consideration some of these viewpoints, food could be defined as any substance or product, liquid or solid, natural, elaborated, or processed that, because of their characteristics, applications, components, preparation, and conservation state, is eaten or drunk by humans as nourishment and enjoyment.

Whatever the definition adopted, it is a general consensus that, almost without exception, food is a complex heterogeneous mixture of a relatively wide range of chemical substances. Also, it is agreed that the two key aspects regarding food are its chemical composition and its physical properties. The reason is that these feature categories determine the nutritional value of the considered food item and its sanitary state, as well as its acceptation by consumers and functional activity. This explains why both food analysis and legislation focus on these two aspects.

Foodstuffs are analyzed for a number of divergent reasons. Governmental and official agencies watch over the accomplishment of legal, labeling, and authenticity requirements. This includes early detection of possible adulterations and fraudulent practices that could result in economic losses or consumers damage. Food analysis is also of primary importance for the food industry, which assesses the quality of the original raw materials and its maintenance through the complete processing, transportation, and conservation process. Scientific researchers are involved in the constant update of the methodologies used to control all the above-mentioned aspects as well as in the development of new analytical procedures that allow the lowering of the allowed maximum residue levels (MRLs) of toxic components and the inclusion of new ones in current legislation, the detailed characterization of food items, and the development of new foodstuffs with added value. Finally, in recent years, there has been an increasing concern by consumers regarding the quality of food. This has partially been motivated by the different scandals originated by food contamination with toxicants and/or forbidden products but, also and more important, by the nowadays accepted relationship between diet and health and the increasing demand of foodstuffs with added nutritional properties. The latter frequently results in the development and addition of new ingredients, whose effect on the original food item at short and long time should also be tested.

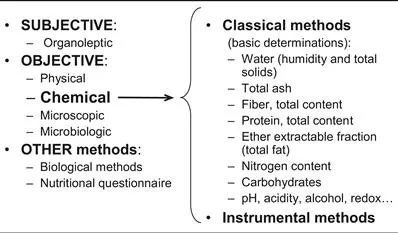

It is evident from previous considerations that food analysis is an extremely wide field in constant evolution involving analysis and chemical determinations of very different nature and with widely divergent goals. These differences translate also to the methods in use for food analysis. As shown in Fig. 1.1, these methods range from subjective (e.g., organoleptic determinations) to objective procedures based on physical, chemical, microscopic, and microbiologic determinations. Other approaches based on, for example, biological determinations and personal questionnaires are also used. This volume reviews the current state-of-the-art and last developments regarding chemical methods and will pay special attention to those based on the use of modern instrumental analytical techniques that, in many instances, have only recently started to be applied in this dynamic research field.

FIGURE 1.1 Different types of methods applied for food analysis.

1.2 Types of Samples and the Analytical Procedure

Food analysis demands chemical determinations at very different levels and for different purposes. As previously indicated, for conventional foods, chemical analysis and controls are applied from independent ingredients and raw materials to the processed products and end-products and, when required, to all intermediate items to guarantee food quality. These types of determinations become especially relevant during the development and implementation of new processing and conservation procedures, or when developing new formula and products.

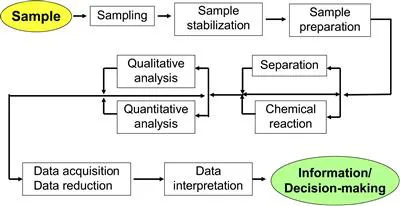

As in any other analytical process, the chemical analysis of foodstuffs involves a number of equally relevant steps with a profound effect on the validity of the data generated (Fig. 1.2).

FIGURE 1.2 Steps in the analytical process.

Although in some cases on-site determination is possible, most samples have to be transported to the laboratory for chemical analysis. Thereby, in many instances, the first issue to consider is how many samples (or subsamples) should be taken, of which size and from where to guarantee the representativeness of the subsamples. Whether random or purposeful, significant consideration needs to be given to the sampling protocol in order to obtain at the end of the analytical process data meaningful and interpretable. Sampling is a complex process that firstly depends on the nature of the matrix to be sampled (solid or liquid), its size (as a whole or as subsamples), and the goal of the analysis (e.g., determination of main components or trace analysis), just to mention a few parameters. In some cases, the procedure and minimum amount of sample necessary to develop a particular analysis is clearly stated in current legislations [see, e.g., (90/642/EEC, 1993) and (2002/63/EC, 2002) for the determination of pesticides residues in products of plant and animal origin]. In other cases, protocols similar to those set in legal texts can be followed or alternative procedures can be adopted as far as they guarantee the representativeness of the sampling process. In-depth discussion on this complex matter is out of the scope of this chapter. Therefore, the reader is referred to texts of a more specialized nature for a detailed discussion on this topic [see, e.g., Curren et al., (2002); Woodget and Cooper, 1987].

Samples should remain unaltered during transportation and storage until the moment of the analysis. As a rule of thumb, samples must be stored for the shortest possible time. When applicable, stabilization procedures that, for example, retard biological action, hydrolysis of chemical compounds, and complexes, and reduce the volatilization of components and adsorption effects, should be adopted.

Once in the laboratory, samples are typically subjected to a number of operations and manipulations before instrumental analysis of the target compounds. These several treatments are grouped under the generic name of sample preparation. The number and nature of these operations and treatments typically depend on the nature and anticipated concentration level of the target compounds, and also on those of the potential matrix interfering components and on the selectivity and sensitivity of the analytical technique selected for final separation and/or detection. Sample preparation would include from the labeling and mechanical processing and homogenization of the received samples, to any type of gravimetric or volumetric measurement carried out. Sample preparation also includes all treatments conducted to decompose the matrix structure in order to perform the fractionation, isolation, and enrichment of the target analytes. Treatments developed to make the tested analyte(s) compatible with the detector (e.g., change of phase and derivatization reactions) and to enhance the sensitivity of the detector are also considered part of the sample preparation protocol.

Table 1.1 presents a simplified overview on food components and food contaminants typically considered for chemical analysis. In most instances, these analytes are also the subject of routine controls. Target compounds include from metals and organometallic species to volatile components. The latter include flavor and fragrances, but also off-flavors that can create problems with unacceptable food products. Many main and minor components with nutritional or added functional value, such as lipids, proteins, carbohydrates, vitamins, and antioxidants, are also analyzed for legal, quality, or research reasons. In addition, food additives, residues, and a large variety of contaminants of different origin and nature are nowadays matter of continuous monitoring and control to ensure the accomplishment of current legislations. Th...