- 500 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Sintering of Advanced Materials

About this book

Sintering is a method for manufacturing components from ceramic or metal powders by heating the powder until the particles adhere to form the component required. The resulting products are characterised by an enhanced density and strength, and are used in a wide range of industries. Sintering of advanced materials: fundamentals and processes reviews important developments in this technology and its applicationsPart one discusses the fundamentals of sintering with chapters on topics such as the thermodynamics of sintering, kinetics and mechanisms of densification, the kinetics of microstructural change and liquid phase sintering. Part two reviews advanced sintering processes including atmospheric sintering, vacuum sintering, microwave sintering, field/current assisted sintering and photonic sintering. Finally, Part three covers sintering of aluminium, titanium and their alloys, refractory metals, ultrahard materials, thin films, ultrafine and nanosized particles for advanced materials.With its distinguished editor and international team of contributors, Sintering of advanced materials: fundamentals and processes reviews the latest advances in sintering and is a standard reference for researchers and engineers involved in the processing of ceramics, powder metallurgy, net-shape manufacturing and those using advanced materials in such sectors as electronics, automotive and aerospace engineering.

- Explores the thermodynamics of sintering including sinter bonding and densification

- Chapters review a variety of sintering methods including atmosphere, vacuum, liquid phase and microwave sintering

- Discusses sintering of a variety of materials featuring refractory metals, super hard materials and functionally graded materials

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Sintering of Advanced Materials by Zhigang Zak Fang in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Tecnología e ingeniería & Ingeniería industrial. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Thermodynamics of sintering

R.M. German, San Diego State University, USA

Abstract:

Particles bond together when heated by a sintering process that is a combination of several atomic level events that include diffusion, creep, viscous flow, plastic flow and evaporation. Significant strengthening occurs in powder compacts due to sintering. Sintering consumes surface energy to build bonds between those particles. Small particles have more surface energy and sinter faster than large particles. Since atomic motion increases with temperature, sintering is accelerated by high temperatures. The thermodynamic driving force for sintering then is found in the surface area, interfacial energies and curvature gradients in the particle system. Actual atomic motion is by several transport mechanisms with concomitant microstructure changes.

Key words

surface energy

surface area

diffusion

creep

viscous flow

plastic flow

particle size

interfacial energy

dihedral angle

contact angle

wetting

curvature

1.1 Introduction

Sintering acts to bond particles together into strong, useful shapes. It is used to fire ceramic pots and in the fabrication of complex, high-performance shapes, such as medical implants. Sintering is irreversible since the particles give up surface energy associated with small particles to build bonds between those particles. Prior to sintering the particles flow easily while after sintering the particles are bonded into a solid body. From a thermodynamic standpoint sinter bonding is driven by the surface energy reduction. Small particles have more surface energy and sinter faster than large particles. Since atomic motion increases with temperature, sintering is accelerated by high temperatures.

The driving force for sintering comes from the high surface energy and curved surface inherent to a powder. The initial stage of sintering corresponds to neck growth between contacting particles where curvature gradients normally dictate the sintering behavior. The intermediate stage corresponds to pore rounding and the onset of grain growth. During the intermediate stage the pores remain interconnected, so the component is not hermetic. Final stage sintering occurs when the pores collapse into closed spheres, giving a reduced impediment to grain growth. Usually the final stage of sintering starts when the component is more than 92% dense. During all three stages, atoms move by several transport mechanisms to create the microstructure changes, including surface diffusion and grain boundary diffusion.

Sintering models include parameters such as particle size and surface area, temperature, time, green density, pressure and atmosphere. Further, the addition of a wetting liquid induces faster sintering. Accordingly, most sintering is performed with a liquid phase present during the heating cycle. These basic thermodynamic attributes are treated in this first chapter.

1.2 The sintering process

Sintering is fundamentally a one-way event. Once sintering starts, surface energy is consumed through particle bonding, resulting in increased compact strength and often a dimensional change. Accordingly, the definition of sintering is as follows:1

Sintering is a thermal treatment for bonding particles into a coherent, predominantly solid structure via mass transport events that often occur on the atomic scale. The bonding leads to improved strength and lower system energy.

The bonding between particles is evident in the scanning electron microscope in terms of the newly formed solid necks between contacting particles. Figure 1.1 illustrates spherical bronze particles after sintering at 800 °C. Necks grow between the contacting spheres, providing strength and rigidity. Longer sintering gives a larger neck and usually more strength. The emergence of the necks between is driven by the system thermodynamics, while the rate of sintering depends mostly on the temperature. At room temperature, the atoms in a material such as bronze are not noticeably mobile, so the particles do not sinter. However, when heated to a temperature near the melting range, the atoms are very mobile. Atomic motion increases with temperature and eventually this motion induces bonding that reduces the overall system energy.

1.1 Scanning electron micrograph of the sintering neck formed between 26 μm bronze particles after sintering at 800 °C.

The energy changes in sintering are usually small, so the rate of change during sintering is slow. In the case of the 26 μm bronze powder shown in Fig. 1.1, which has a solid–vapor surface energy of 1.7 J/m2, the energy per unit mass stored as excess surface area is about 50 J/kg. But not all of this energy can be consumed during sintering, since the structure usually fails to sinter to full density and other interfaces emerge, such as grain boundaries, which add energy into the system. The total surface energy increases as the particle size decreases, so with nanoscale powders smaller than 0.1 μm there is a large driving force for sintering, meaning faster sintering or a lower sintering temperature.

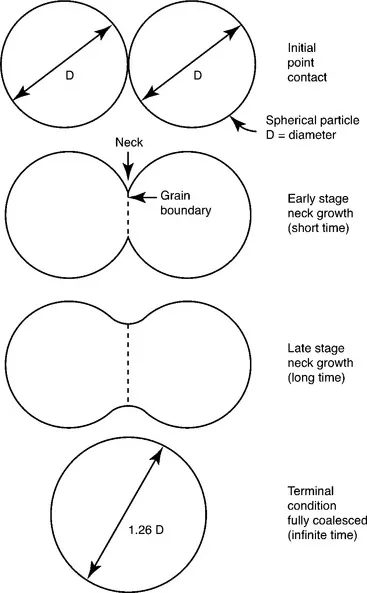

Early models for sintering realized that a sphere affixed to a flat plate presented a large energy difference, since the sphere has much more surface area and by implication more surface energy. Accordingly, early sintering studies measured the neck size between spheres and plates, and subsequently between contacting spheres. The two-sphere model considers two equal-sized spheres in point contact that subsequently fuse to form a single larger sphere with a diameter 1.26 times the starting sphere diameter, as sketched in Fig. 1.2.

1.2 Two-sphere sintering model, where the two spheres grow a neck during sintering that grows to the point where the spheres fuse into a single sphere that is 1.26 times the diameter of the starting spheres.

The rate of particle bonding during sintering depends on temperature, materials, particle size and several processing factors.2 Small particles are more energetic, so they sinter faster. Thus, the thermodynamics of sintering show the importance of smaller powders, while the kinetics of sintering emphasizes the importance of temperature.

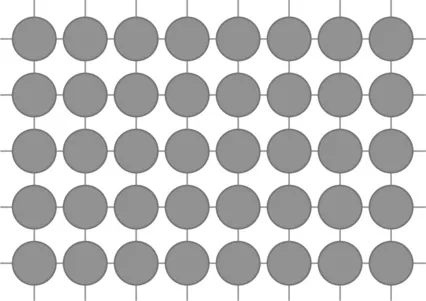

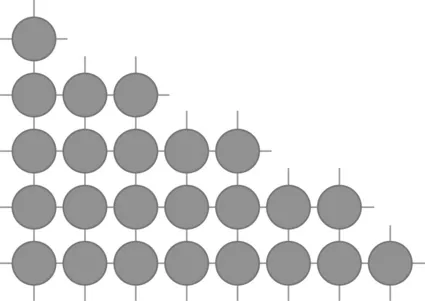

Sintering occurs in stages, as illustrated in Fig. 1.3. Without compaction a model powder system starts at a packing density of 64%, the dense random packing. In the initial sintering stage, the interparticle neck grows to the point where the neck size is less than one-third of the particle size. Often there is little dimensional change so at the most 3% linear shrinkage is seen in the initial stage. For loose spheres this generally corresponds to a density below 70% of theoretical. Intermediate stage sintering implies the necks are larger than one-third the particle size, but less than half the particle size. For a system that densifies, this corresponds to a density range from 70% to 92% for spheres. During the intermediate stage the pores are tubular in character and connected (open) to the external surface. The sintering body is not hermetic so gas can pass in or out during firing. Final stage sintering corresponds to the elimination of the last 8% porosity, where the pores are no longer open to the external surface. Isolated pores, associated with final stage sintering, are filled with the process atmosphere.

1.3 Illustration of the sintering stages with a focus on the changes in pore structure during sintering.

1.3 Surface energy

Surface energy is the thermodynamic cause of sintering. A model of a surface is generated by starting with an ideal crystal, such as shown in Fig. 1.4, where each atomic species occupies specific, repeating sites. Between atoms are bonds, represented by lines. If scissors were used to snip these atomic bonds, then the resulting surface would consist of broken bonds. These bonds provide the atomic interaction responsible for the surface energy. Figure 1.5 illustrates this concept, where the free surface is covered with broken bonds. Surface energy relates to the density of broken bonds (bonds per unit area), so it varies with crystal orientation. Also, since stronger bonding is associated with a higher melting temperature, surface energy is higher for high melting temperature materials.

1.4 An illustration of a perfect crystal where each atom is in a repeating position and atomic bonds are linking the atoms.

1.5 An illustration of how a free surface for a crystalline material results in disrupted atomic bonding; it is the dangling atomic bonds that give surface energy.

An atomic model for the grain boundary would be similar, where broken atomic bonds from the two crystal lattices only partly match. As illustrated in Fig. 1.6, some misorientations lead to more disrupted bonding and high grain boundary energies...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Contributor contact details

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Thermodynamics of sintering

- Chapter 2: Kinetics and mechanisms of densification

- Chapter 3: Path and kinetics of microstructural change in simple sintering

- Chapter 4: Computer modelling of sintering: theory and examples

- Chapter 5: Liquid phase sintering

- Chapter 6: Master sintering curve and its application in sintering of electronic ceramics

- Chapter 7: Atmosphere sintering

- Chapter 8: Vacuum sintering

- Chapter 9: Microwave sintering of ceramics, composites and metal powders

- Chapter 10: Fundamentals and applications of field/current assisted sintering

- Chapter 11: Photonic sintering – an example: photonic curing of silver nanoparticles

- Chapter 12: Sintering of aluminium and its alloys

- Chapter 13: Sintering of titanium and its alloys

- Chapter 14: Sintering of refractory metals

- Chapter 15: Sintering of ultrahard materials

- Chapter 16: Sintering of thin films/constrained sintering

- Chapter 17: Sintering of ultrafine and nanosized particles

- Index