Abstract:

Urban metabolism (UM) is an accounting of inputs into urban systems, the work that gets done and the waste that results from the urban system using those inputs. To date, accounting has been limited to energy, materials, water, nutrients and waste that enter and leave a city at the city scale. This chapter suggests that for UM to be of use in sustainability, UM needs to be downscaled to the census block (for socio-demographic understanding of the users of energy), by sector (to understand how the economy uses energy) and to include life cycle analysis of economic key sectors.

1.1 Introduction: urban metabolism (UM), or urban energy systems

The industrialization of the late nineteenth century was enabled by an unprecedented new energy source: fossil energy. Before, human societies used muscle power from animals and humans. The discovery of fossil energy that packs much more energy bang-for-the-buck has allowed the tremendous growth of cities and economic activity in the twentieth century. This growth has continued into the twenty-first century, which is on course to be the century where more people live in cities than in the countryside – a first in human history. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), as of 2010, more than half of all people live in an urban area, though fewer than 10% of urban dwellers live in megacities (cities of more than ten million people (WHO, 2011)).

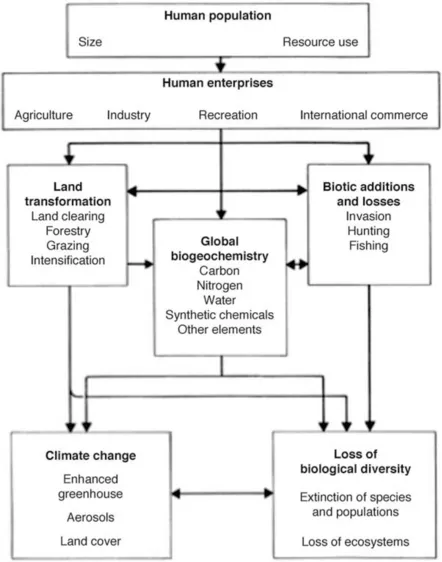

Over the past 100–150 years, the systems to support cities have become increasingly complex and interdependent, accreting infrastructure and activities. Pipelines carrying gasoline, natural gas, water and information crisscross entire countries to supply urban populations. Huge warehousing districts serve as staging areas for the distribution of materials and goods to cities. Transmission lines span landscapes to bring power into urban areas. Cities concentrate energy and resources drawn from near and far for use in relatively compact spaces. This requires enormous investments in infrastructure, both physical and institutional. While on a daily basis most of this has become part of daily life, normalized even, this complex set of physical and human social supply networks is fundamental to the functioning of society and cities; it is also insufficiently examined. In addition, while there is an understanding that cities should become more sustainable and reduce their environmental impact, the actual physical impact of cities on global biogeochemical cycling and ecological processes is understudied (Decker et al., 2000). This means that making genuine reductions is a guessing game since there is not very good information about energy and materials use in cities.

Why is this important? Peter Vitousek and colleagues, in a widely cited 1997 paper in Science, explained that between one-third and one-half of the land surface of the earth has been transformed by human action (Vitousek et al., 1997) (Fig. 1.1). They go on to state that the use of land to yield goods and services represents the most substantial human alteration of the earth system, and that there is real concern that the earth will not be able to sustain the pace and scale of such extractive activity. Better accounting of the material basis upon which urban systems depend seems timely. Furthermore, the relationship between the way urban systems are organized and resource consumption also needs to be taken into account. Are there perverse policies and incentives relative to energy and resource use that reinforce high use rather than parsimonious ones? Is the system simply unexamined such that this high use of resources is not understood well?

1.1 A conceptual model illustrating humanity's direct and indirect effects on the earth system. (source: Vitousek et al., 1997)

Urban metabolism (UM), or the accounting of energy and material flows into cities and the waste products generated, is an initial means to quantify the amount of inputs extracted from the earth for urban use and, ultimately, the physical impact of cities on global biogeochemical cycling and ecological processes. To date, UM has quantified aggregate flows of energy, materials, water, nutrients and waste at the city level. Studies on nearly 50 cities have been conducted by engineers. This chapter suggests the use of UM methods for urban sustainability metrics and proposes additions to improve its utility for sustainability needs.

1.1.1 Evolution of UM analysis

The first UM study was conducted by Abel Wolman in 1965 for a hypothetical city of one million people. His paper ‘The metabolism of cities’ was a pioneering article that framed the city as a closed metabolic unit requiring inputs of materials that are converted and ejected as waste outputs. Wolman foreshadowed ecological footprint analysis, later proposed by Wackernagel and Rees (1996). He noted that the footprints of cities were no longer constrained to the geographic or political boundaries used to define them. A water resources engineer by profession, Wolman was concerned about the pressures on natural systems and resources of an increasingly affluent population (Wolman, 1965). He developed the UM concept as a method for the quantification of inputs – energy, water nutrients, materials and waste – in cities. He identified the three pressing metabolic challenges faced by urban regions as water supply management, sewage disposal and air pollution control. Wolman’s seminal research was the first attempt to highlight system-wide impacts of goods consumption and waste generation in the urban environment (Decker et al., 2000). For sustainability programs to be implemented, understanding the materials and resources cities metabolize, where inputs come from and where waste goes, is critical. UM is a first step in this framework and will contribute to determining what processes are susceptible to alterations such that their impacts can be minimized or eliminated.

Wolman had been part of a group of biophysical and social scientists who participated in a remarkable 1955 international conference on ‘Man’s role in changing the face of the earth’ (Thomas, 1956). The papers at this conference expressed a strong concern about the limited natural base of minerals in the face of rapidly increasing demand. With World War II and the huge increase in the use of minerals and metals harnessed for the war effort, worries about meeting the demand for materials were being expressed in various sectors, including the 1952 report of the President’s Materials Policy Commission (Paley, 1952) in which the federal government surveyed the nation’s mineral resources (Fischer-Kowalski, 2003). This study, for example, stated that the USA would no longer be able to satisfy its own needs for fossil fuels by the mid-1970s and that the nation would become dependent on foreign sources.

It should be noted that a handful of economists pointed to pressures on natural systems and the potential of limits along the lines of Wolman’s concerns beginning in the late 1960s, laying the groundwork for ecological economics. For example, in 1971, Georgescu-Roegen, in The Entropy Law and the Economic Process, argued that the second law of thermodynamics was a limiting factor in economic growth. Thermodynamics is a branch of physics that deals with energy and the work of a system. The first law defines the relationship between the various forms of energy present in a system and the work that system does. It states that matter/energy cannot be created nor can it be destroyed: the quantity of matter/energy remains the same. The second law of thermodynamics takes this concept to the next step. While the quantity may remain the same, the quality deteriorates: once gasoline is burned, it can never be burned again, though its component elements have not disappeared from the earth. Human societies require significant energy inputs that are then dissipated when used in activities, degrading the quality of the input. Ecological economists have argued that it is important to recognize these processes because they will ultimately constrain economic growth as good-quality inputs are used and energy is dissipated into the atmosphere in the form of heat and/or pollution (see articles in the Journal of Ecological Economics, founded in 1989, for such discussions). As high- quality resources are irretrieva...