- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Selected Topics from Neurochemistry

About this book

This book contains up-dated versions of articles which proved very popular when first published in Neurochemistry International. The articles draw attention to developments in a specific field perhaps unfamiliar to the reader, collating observations from a wide area which seem to point in a new direction, giving the author's personal view on a controversial topic, or directing soundly based criticism at some widely held dogma or widely used technique in the neurosciences.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Selected Topics from Neurochemistry by Neville N. Osborne in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Zoology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

SOME FUNDAMENTAL THEORETICAL AND PRACTICAL PROBLEMS ASSOCIATED WITH NEUROCHEMICAL TECHNIQUES IN MAMMALIAN STUDIES

H. HILLMAN, Unity Laboratory, Department of Human Biology and Health, University of Surrey, Guildford, Surrey, GU2 5XH, England

Abstract

The assumptions inherent in (i) a pharmacokinetic experiment in vivo, (ii) a subcellular fractionation, (iii) a chemical assay in an isolated neuron, are listed as three examples of well known neurochemical techniques. From these lists of assumptions a number of general hiatuses in knowledge of the effect of preparation of tissue on the results of experiment have been identified. The importance and different kinds of control experiments are discussed. Comment is made on how the different parameters to which measurements are referred may affect the result of the experiments. Optimal techniques are preferably non-disruptive and noninvasive. A few new techniques are proposed.

CRITIQUE

by

L. HERTZ

AIMS OF NEUROCHEMISTRY

One may summarise the following aims of neurochemistry as the study of: firstly, biochemical processes in the normal central nervous system; secondly, the biochemical processes involved in control by the nervous system of other parts of the body and the ‘feed-back’ from these other parts to the nervous system; thirdly, the biochemical processes and visceral changes triggering neurological and psychological diseases, and the changes in the nervous system resulting from such diseases.

All over the world—especially during the past 35 yr—enormous resources have been devoted to neurobiological research, yet we are still very far from understanding the biochemistry of, for example, thinking, learning, nerve regeneration, manic depression, schizophrenia, multiple sclerosis or the genesis of cancer in the nervous system. This is not to say that pieces of the jig saw have not been found, rather that, so far, not enough of them have been fitted together to make a coherent picture which would indicate, say the biochemistry of thinking, or would lead to a rational treatment for multiple sclerosis.

A number of reasons for this lack of success have been suggested elsewhere (Hillman, 1979). One possible explanation for this is that major shortcomings of techniques currently in use are being overlooked, so it seems opportune to reexamine systematically some of the most current popular techniques, particularly in relation to the assumptions implied by their use and the limitations inherent in the procedures. However, before one does so, it is necessary to state some basic points about the philosophy of research.

THEORETICAL ASPECTS OF RESEARCH

Hierarchy of preparations

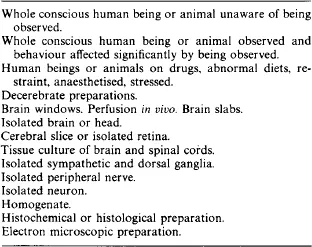

Movement, thinking, learning, active transport and genesis of disease all occur in living animals. Therefore, when one is designing experiments to examine any of these phenomena, the whole living animal must be regarded, prima facie, as the best source of information (Hillman, 1976). Tissue to which powerful chemical reagents has been added, or which has been homogenised, centrifuged, frozen, fixed or dehydrated, must yield information of lesser quality than that derived from living animals, when the results of the two kinds of experiments are incompatible, and when one is attempting to examine properties found only in vivo. This generalisation also applies to light vs electron microscopy, in which the former can be used to observe living animal cells, which the latter so far has not been able to do. It also implies that a metabolising tissue, like a brain slice, for example, must be judged to yield better quality information than a histological section, when the findings arising from the two preparations are incompatible. It thus becomes evident that one may arrange experiments in a hierarchy (Table 1). At the apex stands the whole living conscious normal human being or animal unaffected in respect of the measurements one is making by the experimental or observational procedure (this particularly applies to experiments on the biochemistry of behaviour). Lower down the hierarchy are the anaesthetised, restrained, dieted and inbred animals. Lower still are the tissue slices and single cells. Further down come histological sections and electron microscopic preparations.

Table 1

Hierarchy of preparations

The position in the hierarchy is established empirically, and, therefore, may not be universally agreed.

Findings vs hypotheses

In addition to an experimental hierarchy, there is an obvious logical hierarchy. A finding which makes no or few assumptions is obviously better than one implying many assumptions, especially if they have not been tested. Findings are more valuable than hypotheses. Extrapolations are guesses involving stretching one’s findings beyond the data. From the very nature of such a hierarchy one cannot use a hypotheses as evidence against findings. It is well to note that the following hypotheses are widely regarded as findings: the Davson-Danielli and Singer-Nicholson models of the cell membrane; the presence of a ‘packet’ of acetylcholine in a synaptic vesicle; the chemiosmotic hypotheses of proton transport in mitochondria. One is not decrying the use of hypotheses to design experiments, but it should be emphasised that they cannot be used to contradict findings, upon which their validity alone depends. A hypothesis is a guess, supposition, extrapolation or fantasy. A junior research worker embarking on a new project naturally expects that his highly respected predecessors have tested all the crucial assumptions, but this may not always be true (please see below). However, the farther the original experiments recede into the past, the more assumptions will have been accumulated, and the more inertia or resistance will be engendered in the scientific community against testing the assumptions, or carrying out the relevant control experiments. Nevertheless, obviously neither the long lineage of predecessors who have failed to carry out such experiments, nor the general inertia of any body of dogma against such a necessity, can validate in any way, such partially completed experiments.

Generalisations

If one draws an original conclusion about the chemistry of, say, the frontal cortex of the rat, based on even only four measurements, the following further conclusions are likely to be drawn, unless some well known research worker finds very different values and succeeds in publishing them:

(i) the statistical validity based on these few observations in one experimental series is likely to hold in the same preparation in all animals of that species;

(ii) the finding is likely to be true for other areas of the cerebral cortex of a rat and probably other areas of grey matter;

(iii) it is likely to be true for the grey matter of all other mammalian species;

(iv) it is likely to be independent of the breed, diet, clinical state, circadian rhythms and other variables, unless any of these variables has been shown specifically to alter the chemistry of the area under study;

(v) all these expectations are liable to hold for the foreseeable future.

Such generalisations dare not be made lightly. They are recognised less in neurochemistry than in pharmacology and therapeutics, where species variation is a constant consideration.

Subjective and objective criteria

Everyone would agree that scientific experiment should be objective, but there are several circumstances in which subjectivity may intervene in experiment or publication. These include:

(a) failure of research workers to carry out control experiments, which they have identified or to which their attention has been drawn;

(b) unreadiness to publish experiments which have been done, but which do not fit in with the hypothesis of the research worker;

(c) refusal to recommend for publication in journals or books findings which contradict the views of the referee, who cannot identify objective criteria for such refusal;

(d) influencing research councils to turn down grants to carry out research which will produce unpopular results or is done by people whom the reviewer does not like;

(e) failure of research workers to cite findings which are incompatible with their own hypotheses.

Evidence

It is essential, although not always easy, to distinguish between findings which are compatible with a hypothesis but not crucial to supporting or to denying it, on the one hand—and evidence which bears directly on its validity—on the other hand.

Vertical approach

The creation of a hierarchy (Table 1) helps with another problem. If one wishes to find the site of action of a drug, for example, on the brain, the following are a few of the sort of experiments which may be carried out: one may observe its effect on the behaviour of the whole animal; it may be injected and its distribution within the tissues examined; it may be administered to an animal chronically and its effect on the metabolism or the chemistry of the tissues subsequently excised may be studied; it may be placed in an incubating medium containing cerebral slices, in which its effect on biochemistry is studied; its receptors may be examined in subcellular fractions. Of course, the results of all these experimental investigations should be compatible with each other. However, if the drug has a precise effect in a preparation near the apex of the hierarchy,...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Pergamon publications of related interest

- Copyright

- PREFACE

- LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS

- Chapter 1: SOME FUNDAMENTAL THEORETICAL AND PRACTICAL PROBLEMS ASSOCIATED WITH NEUROCHEMICAL TECHNIQUES IN MAMMALIAN STUDIES

- Chapter 2: METABOLIC AND FUNCTIONAL STUDIES ON POST-MORTEM HUMAN BRAIN

- Chapter 3: COMMUNICATION BETWEEN NEURONES: CURRENT CONCEPTS

- Chapter 4: POSSIBLE MECHANISMS INVOLVED IN THE RELEASE AND MODULATION OF RELEASE OF NEUROACTIVE AGENTS

- Chapter 5: CHOLINERGIC SYSTEMS IN MAMMALIAN BRAIN IDENTIFIED WITH ANTIBODIES AGAINST CHOLINE ACETYLTRANSFERASE

- Chapter 6: NEURAL CONTROL OF MUSCLE

- Chapter 7: NEUROCHEMICAL ASPECTS OF THE OPIOID-INDUCED ‘CATATONIA’

- Chapter 8: POLYAMINE METABOLISM AND FUNCTION IN BRAIN

- Chapter 9: CURRENT STATUS OF THE BIOGENIC AMINE THEORY OF DEPRESSION

- Chapter 10: GABA AND ENDOCRINE REGULATION—RELATION TO NEUROLOGIC-PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS

- Chapter 11: CENTRAL GABA-ERGIC SYSTEMS AND FEEDING BEHAVIOR

- Chapter 12: GABA AND “NEURO-CARDIOVASCULAR” MECHANISMS

- Chapter 13: EFFECTS OF PSYCHOACTIVE AGENTS ON GABA BINDING PROCESSES

- Chapter 14: DO DIFFERENT POPULATIONS OF GABA-RECEPTORS EXIST IN THE VERTEBRATE CNS?

- Chapter 15: ADENOSINE BINDING SITES IN BRAIN; RELATIONSHIP TO ENDOGENOUS LEVELS OF ADENOSINE AND TO ITS PHYSIOLOGICAL AND REGULATORY ROLES

- Chapter 16: PHOTOAFFINITY LABELING OF BENZODIAZEPINE-RECEPTORS: POSSIBLE MECHANISM OF REACTION

- Chapter 17: SEARCHING FOR ENDOGENOUS LIGAND(S) OF CENTRAL BENZODIAZEPINE RECEPTORS

- Chapter 18: NEUROCHEMICAL AND NEUROPHARMACOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF HISTAMINE RECEPTORS

- Chapter 19: NEUROTRANSMITTER-CONTROLLED STEROID HORMONE RECEPTORS IN THE CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM

- Chapter 20: THE TRANSDUCTION OF ENVIRONMENTAL LIGHTING CUES INTO BIOCHEMICAL RHYTHMS VIA MAMMALIAN PINEAL GLAND

- Chapter 21: BIOPTERIN COFACTOR AND MONOAMINE-SYNTHESIZING MONOOXYGENASES

- Chapter 22: REGULATION AND FUNCTION OF PYRIDOXAL PHOSPHATE IN CNS

- Chapter 23: NEUROTRANSMITTER FUNCTION IN THIAMINE-DEFICIENCY ENCEPHALOPATHY

- Chapter 24: B VITAMINS IN THE NERVOUS SYSTEM

- Chapter 25: GLYCOPROTEINS ASSOCIATED WITH MYELIN IN THE CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM

- Chapter 26: GANGLIOSIDES IN THE NERVOUS SYSTEM

- Chapter 27: TUBULIN IN THE NERVOUS SYSTEM

- Chapter 28: CALMODULIN-BINDING PROTEINS IN BRAIN

- SUBJECT INDEX