1.1 Historic and Introductory Comments

In the most general of terms, a composite is a material that consists of two or more constituent materials or phases. Traditional engineering materials (steel, aluminum, etc.) contain impurities that can represent different phases of the same material and fit the broad definition of a composite, but are not considered composites because the elastic modulus or strength of the impurity phase is nearly identical to that of the pure material. The definition of a composite material is flexible and can be augmented to fit specific requirements. In this text a composite material is considered to be one that contains two or more distinct constituents with significantly different macroscopic behavior and a distinct interface between each constituent (on the microscopic level). This includes the continuous fiber laminated composites of primary concern herein, as well as a variety of composites not specifically addressed.

Composite materials have been in existence for many centuries. No record exists as to when people first started using composites. Some of the earliest records of their use date back to the Egyptians, who are credited with the introduction of plywood, papier-mâché, and the use of straw in mud for strengthening bricks. Similarly, the ancient Inca and Mayan civilizations used plant fibers to strengthen bricks and pottery. Swords and armor were plated to add strength in medieval times. An example is the Samurai sword, which was produced by repeated folding and reshaping to form a multilayered composite (it is estimated that several million layers could have been used). Eskimos use moss to strengthen ice in forming igloos. Similarly, it is not uncommon to find horse hair in plaster for enhanced strength. The automotive industry introduced large-scale use of composites with the Chevrolet Corvette. All of these are examples of man-made composite materials. Bamboo, bone, and celery are examples of cellular composites that exist in nature. Muscle tissue is a multidirectional fibrous laminate. There are numerous other examples of both natural and man-made composite materials.

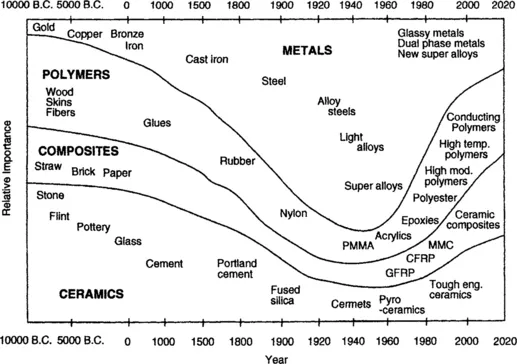

The structural materials most commonly used in design can be categorized in four primary groups: metals, polymers, composites, and ceramics. These materials have been used to various degrees since the beginning of time. Their relative importance to various societies throughout history has fluctuated. Ashby [1] presents a chronological variation of the relative importance of each group from 10,000 B.C. and extrapolates their importance through the year 2020. The information contained in Ashby’s article has been partially reproduced in Figure 1.1. The importance of composites has experienced steady growth since about 1960 and is projected to continue to increase through the next several decades. The relative importance of each group of materials is not associated with any specific unit of measure (net tonnage, etc.). As with many advances throughout history, advances in material technology (from both manufacturing and analysis viewpoints) typically have their origins in military applications. Subsequently, this technology filters into the general population and alters many aspects of society. This has been most recently seen in the marked increase in relative importance of structural materials such as composites starting around 1960, when the race for space dominated many aspects of research and development. Similarly, the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) program in the 1980s prompted increased research activities in the development of new material systems.

Figure 1.1 Relative importance of material development through history (after Ashby [1]).

The composites generally used in structural applications are best classified as high performance. They are typically made from synthetic materials, have high strength-to-weight ratios, and require controlled manufacturing environments foroptimum performance. The aircraft industry uses composites to meet performance requirements beyond the capabilities of metals. The Boeing 757, for example, uses approximately 760 ft3 of composites in its body and wing components, with an additional 361 ft3 used in rudder, elevator, edge panels, and tip fairings. An accurate breakdown of specific components and materials can be found in Reinhart [2]. The B-2 bomber contains carbon and glass fibers, epoxy resin matrices, and high-temperature polyimides as well as other materials in more than 10,000 composite components. It is considered to be one of the first major steps in making aircraft structures primary from composites. Composites are also used in race cars, tennis rackets, golf clubs, and other sports and leisure products. Although composite materials technology has grown rapidly, it is not fully developed. New combinations of fiber/resin systems, and even new materials, are constantly being developed. The best one can hope to do is identify the types of composites that exist through broad characterizations and classifications.

1.2 Characteristics of a Composite Material

The constituents of a composite are generally arranged so that one or more discontinuous phases are embedded in a continuous phase. The discontinuous phase is termed the reinforcement and the continuous phase is the matrix. An exception to this is rubber particles suspended in a rigid rubber matrix, which produces a class of materials known as rubber-modified polymers. In general the reinforcements are much stronger and stiffer than the matrix. Both constituents are required, and each must accomplish specific tasks if the composite is to perform as intended.

A material is generally stronger and stiffer in fiber form than in bulk form. The number of microscopic flaws that act as fracture initiation sites in bulk materials are reduced when the material is drawn into a thinner section. In fiber form the material will typically contain very few microscopic flaws from which cracks may initiate to produce catastrophic failure. Therefore, the strength of the fiber is greater than that of the bulk material. Individual fibers are hard to control and form into useable component...