- 784 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Molecular Biology

About this book

Molecular Biology: Academic Cell Update provides an introduction to the fundamental concepts of molecular biology and its applications. It deliberately covers a broad range of topics to show that molecular biology is applicable to human medicine and health, as well as veterinary medicine, evolution, agriculture, and other areas. The present Update includes journal specific images and test bank. It also offers vocabulary flashcards.

The book begins by defining some basic concepts in genetics such as biochemical pathways, phenotypes and genotypes, chromosomes, and alleles. It explains the characteristics of cells and organisms, DNA, RNA, and proteins. It also describes genetic processes such as transcription, recombination and repair, regulation, and mutations. The chapters on viruses and bacteria discuss their life cycle, diversity, reproduction, and gene transfer. Later chapters cover topics such as molecular evolution; the isolation, purification, detection, and hybridization of DNA; basic molecular cloning techniques; proteomics; and processes such as the polymerase chain reaction, DNA sequencing, and gene expression screening.

- Up to date description of genetic engineering, genomics, and related areas

- Basic concepts followed by more detailed, specific applications

- Hundreds of color illustrations enhance key topics and concepts

- Covers medical, agricultural, and social aspects of molecular biology

- Organized pedagogy includes running glossaries and keynotes (mini-summaries) to hasten comprehension

Trusted by 375,005 students

Access to over 1 million titles for a fair monthly price.

Study more efficiently using our study tools.

Information

Chapter One

Basic Genetics

Gregor Mendel Was the Father of Classical Genetics

Genes Determine Each Step in Biochemical Pathways

Mutants Result from Alterations in Genes

Phenotypes and Genotypes

Chromosomes Are Long, Thin Molecules That Carry Genes

Different Organisms may Have Different Numbers of Chromosomes

Dominant and Recessive Alleles

Partial Dominance, Co-Dominance, Penetrance and Modifier Genes

Genes from Both Parents Are Mixed by Sexual Reproduction

Sex Determination and Sex-Linked Characteristics

Neighboring Genes Are Linked during Inheritance

Recombination during Meiosis Ensures Genetic Diversity

Escherichia coli Is a Model for Bacterial Genetics

Gregor Mendel Was the Father of Classical Genetics

From very ancient times, people have vaguely realized the basic premise of heredity. It was always a presumption that children looked like their fathers and mothers, and that the offspring of animals and plants generally resemble their ancestors. During the 19th century, there was great interest in how closely offspring resembled their parents. Some early investigators measured such quantitative characters as height, weight, or crop yield and analyzed the data statistically. However, they failed to produce any clear-cut theory of inheritance. It is now known that certain properties of higher organisms, such as height or skin color, are due to the combined action of many genes. Consequently, there is a gradation or quantitative variation in such properties. Such multi-gene characteristics caused much confusion for the early geneticists and they are still difficult to analyze, especially if more than two or three genes are involved.

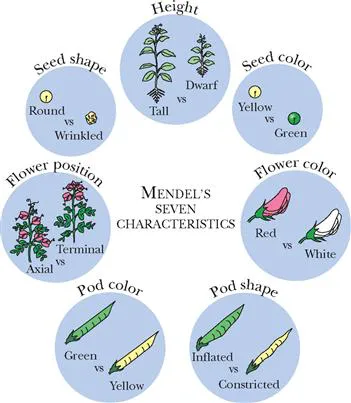

The birth of modern genetics was due to the discoveries of Gregor Mendel (1823–1884), an Augustinian monk who taught natural science to high school students in the town of Brno in Moravia (now part of the Czech Republic). Mendel’s greatest insight was to focus on discrete, clear-cut characters rather than measuring continuously variable properties, such as height or weight. Mendel used pea plants and studied characteristics such as whether the seeds were smooth or wrinkled, whether the flowers were red or white, and whether the pods were yellow or green, etc. When asked if any particular individual inherited these characteristics from its parents, Mendel could respond with a simple “yes” or “no,” rather than “maybe” or “partly.” Such clear-cut, discrete characteristics are known as Mendelian characters (Fig. 1.01).

Figure 1.01 Mendelian Characters in Peas

Mendel chose specific characteristics, such as those shown. As a result he obtained definitive answers to whether or not a particular characteristic is inherited.

Mendel chose specific characteristics, such as those shown. As a result he obtained definitive answers to whether or not a particular characteristic is inherited.

A century before the discovery of the DNA double helix, Mendel realized that inheritance was quantized into discrete units we now call genes.

Today, scientists would attribute each of the characteristics examined by Mendel to a single gene. Genes are units of genetic information and each gene provides the instructions for some property of the organism in question. In addition to those genes that affect the characteristics of the organism more or less directly, there are also many regulatory genes. These control other genes, hence their effects on the organism are less direct and more complex. Each gene may exist in alternative forms known as alleles, which code for different versions of a particular inherited character (such as red versus white flower color). The different alleles of the same gene are closely related, but have minor chemical variations that may produce significantly different outcomes.

The overall nature of an organism is due to the sum of the effects of all of its genes as expressed in a particular environment. The total genetic make-up of an organism is referred to as its genome. In lower organisms such as bacteria, the genome may consist of approximately 2,000 to 6,000 genes, whereas in higher organisms such as plants and animals, there may be up to 50,000 genes.

Etymological Note

Mendel did not use the word “gene.” This term entered the English language in 1911 and was derived from the German “Gen,” short for “Pangen.” This in turn came via French and Latin from the original ancient Greek “genos,”which means birth. “Gene” is related to such modern words as genus, origin, generate, and genesis. In Roman times, a “genius” was a spirit representing the inborn power of individuals.

| allele | One particular version of a gene |

| gene | The entire genetic information |

| genome | The entire genetic information of an individual organism |

| Gregor Mendel | Discovered the basic laws of genetics by crossing pea plants |

| Mendelian character | Trait that is clear cut and discrete and can be unambiguously assigned to one category or another |

Genes Determine Each Step in Biochemical Pathways

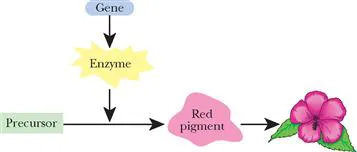

Mendelian genetics was a rather abstract subject, since no one knew what genes were actually made of, or how they operated. The first great leap forward came when biochemists demonstrated that each step in a biochemical pathway was determined by a single gene. Each biosynthetic reaction is carried out by a specific protein known as an enzyme. Each enzyme has the ability to mediate one particular chemical reaction and so the one gene—one enzyme model of genetics (Fig. 1.02) was put forward by G. W. Beadle and E. L. Tatum, who won a Nobel prize for this scheme in 1958. Since then, a variety of exceptions to this simple scheme have been found. For example, some complex enzymes consist of multiple subunits, each of which requires a separate gene.

Figure 1.02 One Gene—One Enzyme

A single gene determines the presence of an enzyme which, in turn, results in a biological characteristic such as a red flower.

A single gene determines the presence of an enzyme which, in turn, results in a biological characteristic such as a red flower.

Beadle and Tatum linked genes to biochemistry by proposing there was one gene for each enzyme.

A gene determining whether flowers are red or white would be responsible for a step in the biosynthetic pathway for red pigment. If this gene were defective, no red pigment would be made and the flowers would take the default coloration—white. It is easy to visualize characters such as the color of flowers, pea pods or seeds in terms of a biosynthetic pathway that makes a pigment. But what about tall versus dwarf plants and round versus wrinkled seeds? It is difficult to interpret these in terms of a single pathway and gene product. Indeed, these properties are affected by the action of many proteins. However, as will be discussed in detail later, certain proteins control the expression of genes rather than acting as enzymes. Some of these regulatory proteins control just one or a few genes whereas others control large numbers of genes. Thus a defective regulatory protein may affect the levels of many other proteins. Modern analysis has shown that some types of dwarfism are due to defects in a single regulatory protein that controls many genes affecting growth. If the concept of “one gene—one enzyme” is broadened to “one gene—one protein,” it still applies in most cases. [There are of course exceptions. Perhaps the most important is that in higher organisms multiple related proteins may sometimes be made from the same gene by alternative patterns of splicing at the RNA level, as discussed in Chapter 12.]

Much of modern molecular biology deals with how genes are regulated. (See Chapters 9, 10 and 11.)

| enzyme | A protein that carries out a chemical reaction |

| protein | A polymer made from amino acid... |

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter One. Basic Genetics

- Chapter Two. Cells and Organisms

- Chapter Three. DNA, RNA and Protein

- Chapter Four. Genes, Genomes and DNA

- Chapter Five. Cell Division and DNA Replication

- Chapter Six. Transcription of Genes

- Chapter Seven. Protein Structure and function

- Chapter Eight. Protein Synthesis

- Chapter Nine. Regulation of Transcription in Prokaryotes

- Chapter Ten. Regulation of Transcription in Eukaryotes

- Chapter Eleven. Regulation at the RNA Level

- Chapter Twelve. Processing of RNA

- Chapter Thirteen. Mutations

- Chapter Fourteen. Recombination and Repair

- Chapter Fifteen. Mobile DNA

- Chapter Sixteen. Plasmids

- Chapter Seventeen. Viruses

- Chapter Eighteen. Bacterial Genetics

- Chapter Nineteen. Diversity of Lower Eukaryotes

- Chapter Twenty. Molecular Evolution

- Chapter Twenty - One. Nucleic Acids: Isolation, Purification, Detection, and Hybridization

- Chapter Twenty - Two. Recombinant DNA Technology

- Chapter Twenty - Three. The Polymerase Chain Reaction

- Chapter Twenty - Four. Genomics and DNA Sequencing

- Chapter Twenty - Five. Analysis of Gene Expression

- Chapter Twenty - Six. Proteomics: The Global Analysis of Proteins

- Glossary

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Molecular Biology by David P. Clark in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.