MARTHA HYNECK, JOHN DENT and JERRY B. HOOK, Research and Development, Smith Kline Beecham Pharmaceuticals, 709 Swedeland Road, King of Prussia, Pennsylvania 19406–2799, USA

Publisher Summary

This chapter discusses that optical activity is caused by molecular asymmetry and that nonsuperimposable mirror-image structures results from this molecular asymmetry. There is a hypothesis that the chiral nature of compounds is because of the fact that carbon constituents can have a non-planar spatial arrangement giving rise to nonsuperimposable mirror images. Most naturally occurring medicinal agents exist in their optically active or single isomer form, such as quinidine and quinine, (-)-morphine, and (+)-digitoxin. However, many synthetic chemicals are produced as the optically inactive racemate. Because of potential pharmacological, pharmacokinetic, and toxicological issues, some scientists suggest that only single isomers should be considered for drug development and regulatory approval. Pharmacokinetic investigations into the disposition of enantiomers have enhanced the understanding of racemic drug action and have helped to understand previously inexplicable pharmacodynamic outcomes following administration of racemates to patients.

Introduction

The field of stereochemistry has been developing since the early 1800s when Jean-Baptiste Biot, a French physicist, discovered optical activity in 1815. By the middle of the 19th century, Louis Pasteur had performed the first resolution of a racemic mixture, d- and l-tartaric acid. From this work Pasteur made the remarkable proposal that optical activity was caused by molecular asymmetry and that nonsuperimposable mirror-image structures resulted from this molecular asymmetry. Despite considerable scepticism within the community of chemists, scientists from several countries continued exploring this new field and with each new scientific contribution the relationship between optical activity and molecular asymmetry unfolded. By the end of the 18th century, Van’t Hoff of Holland and Le Bel of France strengthened Pasteur’s proposal by hypothesizing that the chiral nature of compounds was due to the fact that carbon constituents could have a non-planar spatial arrangement giving rise to nonsuperimposable mirror images (Drayer, 1988a).

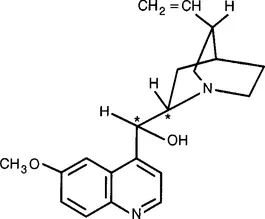

Today we realize that most naturally occurring medicinal agents exist in their optically active or single isomer form, such as quinidine and quinine (Fig. 1), (–)-morphine and (+)-digitoxin. However, many synthetic chemicals are produced as the optically inactive racemate. According to a survey reported in 1984, nearly 400 racemates were prescribed for patients in the 1970s and 1980s (Mason, 1984). The fact that so many drugs are administered as racemic mixtures has led to considerable concern and debate (Ariens, 1984; Caldwell et al., 1988). Because of potential pharmacological, pharmacokinetic and toxicological issues, some scientists suggest that only single isomers should be considered for drug development and regulatory approval. In support of racemic drug development, proponents cite examples of racemic compounds that have been administered for years without untoward effects, and the technical difficulties associated with large-scale production of single isomers.

Fig. 1 Structure of quinidine and quinine.

In the past few decades pharmacological and toxicological investigations have clearly demonstrated significant differences in the biological activity of some isomeric pairs. Recently, pharmacokinetic investigations into the disposition of enantiomers have enhanced our understanding of racemic drug action and have helped us to understand previously inexplicable pharmacodynamic outcomes following administration of racemates to patients.

2 Terminology

A myriad of terms in stereochemistry are used to define molecules and to describe the relationship between molecules and receptors in the body (Wainer and Marcotte, 1988; Caldwell et al., 1988). This section is not meant to be an exhaustive review of the field, but to cover the major terms and concepts to be used.

Isomers are unique molecular entities composed of the same chemical constituents with common structural characteristics. Stereoisomers are those isomers whose atoms, or groups of atoms, differ with regard to spatial arrangement of the ligands. Stereoisomers can be either geometric or optical isomers. Geometric isomers are stereoisomers without optically active centres; for these compounds terminology such as cis or Z isomer (meaning together or same side), and trans or E isomer (meaning opposite side) are used to describe the spatial arrangement.

Optical isomers are a subset of stereoisomers, from which at least two isomers are optically active; these compounds are said to possess chiral or asymmetrical centres. The most common chiral centre is carbon, but phosphorus, sulphur and nitrogen can also form chiral centres. If the isomer and its mirror image are not superimposable, the pair are referred to as enantiomers or optical antipodes. A mixture of equal portions (50/50) of each enantiomer is called a racemate. Optical isomers that are not enantiomers are called diastereoisomers or diastereomers. One type of diastereomer is a molecule with two chiral centres; all four isomers of this diastereomer are not superimposable mirror images of each other. Whereas enantiomers have physically identical characteristics such as lipid solubility and melting/ boiling points, diastereomers can have different chemical and physical characteristics.

The earliest method of differentiating one enantiomer from its antipode was to assign the d or (+) designation to stereoisomers which caused a clockwise rotation of a beam of polarized light, and l or (–) to stereoisomers which cause a counterclockwise rotation of the polarized light. Since this system did not describe the actual spatial arrangement, the Fischer convention was developed (Wichelhaus et al., 1919; Freudenberg, 1966). In this system, the molecule had to be converted to a compound of known configuration, such as (+)-glyceraldehyde and then named accordingly. Due to the difficulty of the chemical transformation, the awkwardness of the convention in some situations (i.e. diastereomers) and the confusion between small and capital letter system (d and d), the convention has fallen into disfavour.

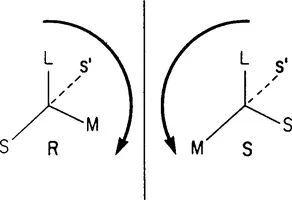

The Cahn–Ingold–Prelog convention is currently recommended for specifying the configuration of the isomers (Cahn et al., 1966). In this method, the ligands around the chiral centre are ‘sized’ according to their atomic number (Fig. 2). The molecule is then positioned with the smallest ligand(s) away from the viewer (‘into the page’). If the sequence of the remaining three ligands are arranged so that the largest (L) to the smallest (S) size is in a clockwise manner, the molecule is assigned the R or rectus; the counterclockwise sequencing is given the S or sinister designation.

Fig. 2 The Cahn–Ingold-Prelog convention. Reprinted from Wainer and Marcotte (1988) by courtesy of Marcel Dekker Inc.

Two other terms may be used to compare the pharmacological activity of ...